Chapter 4: Limitations on Copyrightability

[*41]A. The Idea-Expression Dichotomy

The term “idea-expression dichotomy” encapsulates a fundamental precept of copyright law, which is that copyright protection is only available for the expression of ideas, not for the underlying ideas themselves.[1] The seminal articulation of the dichotomy can be found in Baker v. Selden,[2] a landmark decision of the Supreme Court handed down in 1879. It involved a book describing a practice known today as double-entry bookkeeping, which was apparently an important innovation in accounting practices. The owner of the copyright in the book sought to use the copyright to exclude others from commercializing the method of accounting described in the book. The Court rejected this attempted overreach, holding that the exclusive rights of the copyright only encompassed the author’s expression of the idea of double-entry bookkeeping, not the underlying idea itself. The Court explained that this would be analogous to “an author of a treatise on the composition and use of medicines attempting to use the copyright on the treatise to exclude others from the medicines and their use described therein.” As explained by the Court:

The description of the art in a book, though entitled to the benefit of copyright, lays no foundation for an exclusive claim to the art itself. The object of the one is explanation; the object of the other is use. The former may be secured by copyright. The latter can only be secured, if it can be secured all, by [a patent].

The holding of Baker was essentially codified in 102(b), which provides the statutory basis for the idea-expression dichotomy:

In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.

17 U.S.C. § 102(b)

As discussed in detail later in this casebook, the idea-expression dichotomy appears in a variety of contexts throughout copyright law, including the assessment of whether a work is copyrightable, or whether the copyright in a work has been infringed. It is also the basis for some of the important doctrines of copyright law, including merger and thin[3] copyright protection, which are discussed below.

The essence of the idea-expression dichotomy is that copyright law grants an author the right to exclude others from reproducing the author’s expression of an idea, but not the idea itself. Allowing copyright law to extend to ideas, facts, utilitarian processes, etc., would create serious public policy concerns. For example, it would restrict the ability of people to express and discuss ideas, potentially impinging on the First Amendment. Tying up facts and ideas with copyright could also harm the progress of science and future creativity, by denying others the right to build upon those facts and ideas, a concern discussed by the Supreme Court in Feist. Granting authors exclusive rights in their expression of ideas, on the other hand, is [*42] seen as promoting public policy by providing an incentive for the creation and dissemination of expressive works. The idea-expression dichotomy thus represents a means of providing balance, hopefully allowing sufficient incentive for authors to create expressive works without over-protecting in a manner that unduly restricts the ability of others to discuss and build upon the underlying ideas.

__________

Some things to consider when reading Nichols:

- This case is often cited for Judge Hands explanation of his “abstractions” test, which is still used by courts to discern between a copyrighted work’s ideas, which are freely available for anyone to copy, and the work’s expression of those ideas, which is protected.

- This case is also noted for Judge Hand’s discussion of the potentially copyrightable elements of a play, particularly the “characters and sequence of incidents.”

- This case introduces the concept of copyright in characters, a topic which will come up again later in this casebook.

Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp.

45 F.2d 119 (2d Cir. 1930)

L. HAND, Circuit Judge.

The plaintiff is the author of a play, ‘Abie’s Irish Rose,‘ which it may be assumed was properly copyrighted. The defendant produced publicly a motion picture play, ‘The Cohens and The Kellys,‘ which the plaintiff alleges was taken from it. As we think the defendant’s play too unlike the plaintiff’s to be an infringement, we may assume, arguendo, that in some details the defendant used the plaintiff’s play, as will subsequently appear, though we do not so decide. It therefore becomes necessary to give an outline of the two plays.

‘Abie’s Irish Rose‘ presents a Jewish family living in prosperous circumstances in New York. The father, a widower, is in business as a merchant, in which his son and only child helps him. The boy has philandered with young women, who to his father’s great disgust have always been Gentiles, for he is obsessed with a passion that his daughter-in-law shall be an orthodox Jewess. When the play opens the son, who has been courting a young Irish Catholic girl, has already married her secretly before a Protestant minister, and is concerned to soften the blow for his father, by securing a favorable impression of his bride, while concealing her faith and race. To accomplish this he introduces her to his father at his home as a Jewess, and lets it appear that he is interested in her, though he conceals the marriage. The girl somewhat reluctantly falls in with the plan; the father takes the bait, becomes infatuated with the girl, concludes that they must marry, and assumes that of course they will, if he so decides. He calls in a rabbi, and prepares for the wedding according to the Jewish rite.

Meanwhile the girl’s father, also a widower, who lives in California, and is as intense in his own religious [*43] antagonism as the Jew, has been called to New York, supposing that his daughter is to marry an Irishman and a Catholic. Accompanied by a priest, he arrives at the house at the moment when the marriage is being celebrated, but too late to prevent it and the two fathers, each infuriated by the proposed union of his child to a heretic, fall into unseemly and grotesque antics. The priest and the rabbi become friendly, exchange trite sentiments about religion, and agree that the match is good. Apparently out of abundant caution, the priest celebrates the marriage for a third time, while the girl’s father is inveigled away. The second act closes with each father, still outraged, seeking to find some way by which the union, thus trebly insured, may be dissolved.

The last act takes place about a year later, the young couple having meanwhile been abjured by each father, and left to their own resources. They have had twins, a boy and a girl, but their fathers know no more than that a child has been born. At Christmas each, led by his craving to see his grandchild, goes separately to the young folks’ home, where they encounter each other, each laden with gifts, one for a boy, the other for a girl. After some slapstick comedy, depending upon the insistence of each that he is right about the sex of the grandchild, they become reconciled when they learn the truth, and that each child is to bear the given name of a grandparent. The curtain falls as the fathers are exchanging amenities, and the Jew giving evidence of an abatement in the strictness of his orthodoxy.

‘The Cohens and The Kellys‘ presents two families, Jewish and Irish, living side by side in the poorer quarters of New York in a state of perpetual enmity. The wives in both cases are still living, and share in the mutual animosity, as do two small sons, and even the respective dogs. The Jews have a daughter, the Irish a son; the Jewish father is in the clothing business; the Irishman is a policeman. The children are in love with each other, and secretly marry, apparently after the play opens. The Jew, being in great financial straits, learns from a lawyer that he has fallen heir to a large fortune from a great-aunt, and moves into a great house, fitted luxuriously. Here he and his family live in vulgar ostentation, and here the Irish boy seeks out his Jewish bride, and is chased away by the angry father. The Jew then abuses the Irishman over the telephone, and both become hysterically excited. The extremity of his feelings make the Jew sick, so that he must go to Florida for a rest, just before which the daughter discloses her marriage to her mother.

On his return the Jew finds that his daughter has borne a child; at first he suspects the lawyer, but eventually learns the truth and is overcome with anger at such a low alliance. Meanwhile, the Irish family who have been forbidden to see the grandchild, go to the Jew’s house, and after a violent scene between the two fathers in which the Jew disowns his daughter, who decides to go back with her husband, the Irishman takes her back with her baby to his own poor lodgings. The lawyer, who had hoped to marry the Jew’s daughter, seeing his plan foiled, tells the Jew that his fortune really belongs to the Irishman, who was also related to the dead woman, but offers to conceal his knowledge, if the Jew will share the loot. This the Jew repudiates, and, leaving the astonished lawyer, walks through the rain to his enemy’s house to surrender the property. He arrives in great dejection, tells the truth, and abjectly turns to leave. A reconciliation ensues, the Irishman agreeing to share with him equally. The Jew shows some interest in his grandchild, though this is at most a minor motive in the reconciliation, and the curtain falls while the two are in their cups, the Jew insisting that in the firm name for the business, which they are to carry on jointly, his name shall stand first.

It is of course essential to any protection of literary property, whether at common-law or under the statute, that the right cannot be limited literally to the text, else a plagiarist would escape by immaterial variations. That has never been the law, but, as soon as literal appropriation ceases to be the test, the whole matter [*44] is necessarily at large, so that, as was recently well said by a distinguished judge, the decisions cannot help much in a new case. Upon any work, and especially upon a play, a great number of patterns of increasing generality will fit equally well, as more and more of the incident is left out. The last may perhaps be no more than the most general statement of what the play is about, and at times might consist only of its title; but there is a point in this series of abstractions where they are no longer protected, since otherwise the playwright could prevent the use of his ‘ideas,‘ to which, apart from their expression, his property is never extended. Nobody has ever been able to fix that boundary, and nobody ever can. As respects plays, the controversy chiefly centers upon the characters and sequence of incident, these being the substance.

We do not doubt that two plays may correspond in plot closely enough for infringement. How far that correspondence must go is another matter. Nor need we hold that the same may not be true as to the characters, quite independently of the “plot” proper, though, as far as we know such a case has never arisen. If Twelfth Night were copyrighted, it is quite possible that a second comer might so closely imitate Sir Toby Belch or Malvolio as to infringe, but it would not be enough that for one of his characters he cast a riotous knight who kept wassail to the discomfort of the household, or a vain and foppish steward who became amorous of his mistress. These would be no more than Shakespeare’s “ideas” in the play, as little capable of monopoly as Einstein’s Doctrine of Relativity, or Darwin’s theory of the Origin of Species. It follows that the less developed the characters, the less they can be copyrighted; that is the penalty an author must bear for marking them too indistinctly.

In the two plays at bar we think both as to incident and character, the defendant took no more— assuming that it took anything at all— than the law allowed. The stories are quite different. One is of a religious zealot who insists upon his child’s marrying no one outside his faith; opposed by another who is in this respect just like him, and is his foil. Their difference in race is merely an obbligato to the main theme, religion. They sink their differences through grandparental pride and affection. In the other, zealotry is wholly absent; religion does not even appear. It is true that the parents are hostile to each other in part because they differ in race; but the marriage of their son to a Jew does no apparently offend the Irish family at all, and it exacerbates the existing animosity of the Jew, principally because he has become rich, when he learns it. They are reconciled through the honesty of the Jew and the generosity of the Irishman; the grandchild has nothing whatever to do with it. The only matter common to the two is a quarrel between a Jewish and an Irish father, the marriage of their children, the birth of grandchildren and a reconciliation.

If the defendant took so much from the plaintiff, it may well have been because her amazing success seemed to prove that this was a subject of enduring popularity. Even so, granting that the plaintiff’s play was wholly original, and assuming that novelty is not essential to a copyright, there is no monopoly in such a background. Though the plaintiff discovered the vein, she could not keep it to herself; so defined, the theme was too generalized an abstraction from what she wrote. It was only a part of her “ideas.”

Nor does she fare better as to her characters. It is indeed scarcely credible that she should not have been aware of those stock figures, the low comedy Jew and Irishman. The defendant has not taken from her more than their prototypes have contained for many decades. If so, obviously so to generalize her copyright, would allow her to cover what was not original with her. But we need not hold this as matter of fact, much as we might be justified. Even though we take it that she devised her figures out of her brain de novo, still the defendant was within its rights. [*45]

There are but four characters common to both plays, the lovers and the fathers. The lovers are so faintly indicated as to be no more than stage properties. They are loving and fertile; that is really all that can be said of them, and anyone else is quite within his rights if he puts loving and fertile lovers in a play of his own, wherever he gets the cue. The Plaintiff’s Jew is quite unlike the defendant’s. His obsession in his religion, on which depends such racial animosity as he has. He is affectionate, warm and patriarchal. None of these fit the defendant’s Jew, who shows affection for his daughter only once, and who has none but the most superficial interest in his grandchild. He is tricky, ostentatious and vulgar, only by misfortune redeemed into honesty. Both are grotesque, extravagant and quarrelsome; both are fond of display; but these common qualities make up only a small part of their simple pictures, no more than any one might lift if he chose. The Irish fathers are even more unlike; the plaintiff’s a mere symbol for religious fanaticism and patriarchal pride, scarcely a character at all. Neither quality appears in the defendant’s, for while he goes to get his grandchild, it is rather out of a truculent determination not to be forbidden, than from pride in his progeny. For the rest he is only a grotesque hobbledehoy, used for low comedy of the most conventional sort, which any one might borrow, if he chanced not to know the exemplar.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Nichols

Question 1. True or False: It is possible for one to copy substantially from another’s copyrighted work, without authorization, without incurring liability for copyright infringement. [*46]

Socratic Script

Why does the court assume, in the first paragraph of the decision, that plaintiff’s play “was properly copyrighted” and that “in some details the defendant used the plaintiff’s play”?

What is the “abstractions test,” and what role does it play in determining liability for copyright infringement?

Some things to consider when reading Sissom:

- This case illustrates application of the idea-expression dichotomy with respect to historical facts, a form of “idea” that cannot be protected by copyright.

- Even though the plaintiff’s book is copyrighted, the facts presented in the book are not, so the public is free to copy the facts without incurring liability for copyright infringement. As a general matter, it is perfectly all right to copy material from a copyrighted work, so long as only uncopyrightable elements, i.e., ideas, such as facts, are copied, not the expression of those ideas.

- Note the court’s brief discussion of state common law copyright and its preemption by the 1976 Copyright Act, both mentioned earlier in this casebook.

Sissom v. Snow

626 F. App’x 163 (7th Cir. 2015)

The circumstances surrounding the investigation of three murders in Indianapolis, Indiana, provided the subject matter for two non-fiction books, a 2006 book by Carol Sissom, and a 2012 book by Robert Snow. In this appeal challenging the dismissal of her suit against Snow and his booksellers, Sissom contends that Snow’s book infringes on the copyright of her composition. Because Snow’s book restates only historical events, the defendants did not infringe on any protected expression, so we affirm. [*47]

In December 1971 three Indianapolis businessmen were murdered at a house on the city’s east side. Police were unable to solve the crime, which gained notoriety as the years passed and no one was identified as the assailant. The case was still cold 20 years later when Sissom, a freelance journalist, became interested in it. She first investigated the case while writing a series of newspaper articles, and then continued the investigation for its own sake. Eventually Sissom believed she had found the killers, concluding that they were motivated either by jealousy or secret payments from the Nixon Administration to cover up illegal campaign contributions from Jimmy Hoffa. The men accused by Sissom were charged with the murders, but the charges were quickly dropped, and the case remained open. In 2003 the Indianapolis police received a letter confessing to the murders. Sissom got wind of the confession, and, believing it to have validated her work, soon memorialized her investigation and conclusions in book form, first in her 2006 book The LaSalle Street Murders, and a few years later in a trilogy bearing the same name.

The 2003 letter, which had been written by an individual other than those charged in connection with Sissom’s investigation, prompted an Indianapolis detective to take a fresh look at the case. That detective ultimately concluded that the letter’s author, who claimed that he had been paid to commit the murders in order to obtain an insurance payout, was telling the truth. On the basis of the detective’s conclusion, the Indianapolis police decided to close the case. That closure precipitated Robert Snow’s Slaughter on North LaSalle, a book detailing the original investigation, Sissom’s work in the 90s, and the case’s conclusion.

Though critical of Sissom’s methods and conclusions, the middle third of Snow’s account relies heavily on Sissom’s 2006 work, and he credits Sissom’s book as his source of information about her investigation and findings. In that middle portion, Snow restates many historical facts that appear in The LaSalle Street Murders. We provide three illustrative examples.

First, early on in her book, Sissom explained how she began her investigation: “I made my first inquiry at the Marion County Public Library. It was there that a woman told me about a sensational murder case that happened when I was just a small school girl…. When I looked at my calendar I realized that the 20–year anniversary of the LaSalle Street Murders was coming up.” Snow summarized this information about Sissom’s start as follows: “Eventually, a librarian at the Indianapolis Marion County Public Library pointed [Sissom] toward the North LaSalle Street Murders, still unsolved and whose twentieth anniversary was coming up in December of that year.” A second example reflects how Sissom got her first “break” in the case. She wrote that it came when she located a potential witness: “My second goal was to find [Margo], the waitress at the bar, ‘Tommy’s Starlight Palladium’ in 1971…. With a little tenacity—and the speed of the fingers on my right hand dancing on my telephone keyboard, I found [Margo]! She was a go-go dancer at a seedy establishment near South Meridian Street, not too far from downtown Indianapolis.” Snow recapped how Sissom found Margo: “Next, [Sissom] set out to find the woman named Margo, whom she said she eventually located working at a run-down bar in Indianapolis.” As a final example, Sissom elaborated on her interaction with Floyd Chastain, a convicted murderer incarcerated in a Florida state prison and one of the men she eventually accused of the murders. About their first conversation Sissom wrote: “The next day, I received a call that I will never forget as long as I live. It was a phone call that pierced my afternoon with both excitement and terror at the same time. It was about 2:20 p.m. and a brilliant, sunny day.” Snow summarized the same events: “But then, on September 1st, 1992, Chastain called [Sissom] from the prison in Florida.”

Similarities like these in Snow’s book prompted Sissom to bring this action for copyright infringement against Snow and others in the chain of distribution. Sissom’s complaint asserted generally that part of [*48]Snow’s book was an unlawful paraphrase of her own works on the subject, and she later identified 194 specific instances (of which we have just given three representative examples) where Slaughter on North LaSalle, she believed, unlawfully copied from The LaSalle Street Murders. (Sissom also brought claims for intentional infliction of emotional distress and defamation, but she voluntarily dismissed those supplemental claims with prejudice, and then repleaded only the copyright claim, so we forgo any analysis of those supplemental claims.)

The defendants moved to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim, and submitted to the district court the two books that we have mentioned and that Sissom discusses throughout her complaint. The district court granted the motion, concluding that Snow’s book relied on Sissom’s only for non-copyrightable facts, and so the defendants were entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

Sissom concedes that Snow could lawfully use factual bits and pieces of her work, but contends that his extensive reliance on her book infringed upon her copyright. Sissom correctly points out that the middle portion of Snow’s book essentially restates the same chronology of events and the conclusions that Sissom reached in hers, using the third person rather than the first. Sissom appears to invoke the concept of a derivative work, which the Copyright Act defines as “a work based upon one or more preexisting works,” a definition that includes works “consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, or elaborations.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. The creator of a derivative work infringes on the protected portion of the original unless that person obtains a license from the owner of the underlying copyright.

But none of the material that Sissom says is taken from her book is derivative of protectable material. The middle part of Snow’s book, from the chronology of Sissom’s investigation to her ultimate conclusions, simply restates historical events—the murder investigation and Sissom’s role in it—and adds a bit of Snow’s own commentary about those events. It is a foundation of copyright law that only the form of an author’s expression is protectable, not the facts or ideas being expressed. This principle remains true no matter how much factual content is borrowed. Because Snow merely retold historical events using his own, more succinct style of expression, he did not appropriate any copyrightable expression. Therefore Sissom’s copyright claim fails.

Sissom counters that her book is not entirely factual, and thus Snow’s retelling necessarily infringes on her creation. To prove that her account is part fiction, she refers us to the “Disclaimer Page” that prefaces The LaSalle Street Murders. But that page undercuts her argument. There, she emphasizes that the book is “the true story” and “every part of this book is accurate,” consisting of “verif[ied] facts.” Based on her admission, then, the book’s content is unprotected factual material. It is true that later in the disclaimer she backpedals, suggesting that some parts of her book “have been fictionalized in order to move the story along.” But in her complaint and her opposition to the motion to dismiss, she asserts that the defendants infringed only on those portions of her book that describe “her feelings, perceptions, thoughts and actions.” These are actual, historical events. And since, as we have observed, historical truth is not protected expression, she fails to support her federal claim for infringement.

In addition to her federal claim, Sissom raises a host of novel, confusing, and ultimately meritless arguments generally based on Indiana common law. Asserting that Snow’s work has invaded her privacy, she first refers us to the common law of copyright. Any argument grounded in a right of privacy is puzzling, given that Sissom published her own book and inserted herself into the historical record of the case. But in any event, [*49] while the common law of copyright could be invoked in limited circumstances to protect personal privacy, it does not apply here because it was abolished for works like Sissom’s created after 1977.

[4]

__________

Check Your Understanding – Sissom

Question 1. True or false: The defendant in Sissom was not held liable for copyright infringement because the plaintiff could not prove that the defendant had copied more than a de minimis amount of the plaintiff’s copyrighted book.

Some things to consider when reading Lotus:

- This case involves competing computer spreadsheet programs. Microsoft Excel is an example of a computer spreadsheet program with which today’s students are generally more familiar.

- The basis for the district court’s determination that the Lotus menu command hierarchy was copyrightable.

- The basis for the First Circuit’s determination that the Lotus menu command hierarchy was an uncopyrightable “method of operation.”

- The court’s analogy between the Lotus menu command hierarchy and the buttons used to control a VCR.

- The policy considerations at play in the case, as discussed by both the majority and the dissent.

- Although Lotus is still good law in the First Circuit, see e-STEPS, LLC v. Americas Leading Fin., LLC, 2021 WL 1157024, at *8 (D.P.R. Mar. 24, 2021), other circuits have rejected Lotus’s holding that expression that is part of a method of operation is not copyrightable, as discussed by the Ninth Circuit in a case that appears later in this casebook, Oracle Am., Inc. v. Google Inc., 750 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

Lotus Dev. Corp. v. Borland Int’l, Inc.

49 F.3d 807 (1st Cir. 1995)

STAHL, Circuit Judge.

This appeal requires us to decide whether a computer menu command hierarchy is copyrightable subject matter. In particular, we must decide whether, as the district court held, plaintiff-appellee Lotus [*50] Development Corporation’s copyright in Lotus 1–2–3, a computer spreadsheet program, was infringed by defendant-appellant Borland International, Inc., when Borland copied the Lotus 1–2–3 menu command hierarchy into its Quattro and Quattro Pro computer spreadsheet programs.

I.

Background

Lotus 1–2–3 is a spreadsheet program that enables users to perform accounting functions electronically on a computer. Users manipulate and control the program via a series of menu commands, such as “Copy,” “Print,” and “Quit.” Users choose commands either by highlighting them on the screen or by typing their first letter. In all, Lotus 1–2–3 has 469 commands arranged into more than 50 menus and submenus.

Lotus 1–2–3, like many computer programs, allows users to write what are called “macros.” By writing a macro, a user can designate a series of command choices with a single macro keystroke. Then, to execute that series of commands in multiple parts of the spreadsheet, rather than typing the whole series each time, the user only needs to type the single pre-programmed macro keystroke, causing the program to recall and perform the designated series of commands automatically. Thus, Lotus 1–2–3 macros shorten the time needed to set up and operate the program.

Borland released its first Quattro program to the public in 1987, after Borland’s engineers had labored over its development for nearly three years. Borland’s objective was to develop a spreadsheet program far superior to existing programs, including Lotus 1–2–3.

The district court found, and Borland does not now contest, that Borland included in its Quattro and Quattro Pro version 1.0 programs a virtually identical copy of the entire 1–2–3 menu tree. In so doing, Borland did not copy any of Lotus’s underlying computer code; it copied only the words and structure of Lotus’s menu command hierarchy. Borland included the Lotus menu command hierarchy in its programs to make them compatible with Lotus 1–2–3 so that spreadsheet users who were already familiar with Lotus 1–2–3 would be able to switch to the Borland programs without having to learn new commands or rewrite their Lotus macros.

In its Quattro and Quattro Pro version 1.0 programs, Borland achieved compatibility with Lotus 1–2–3 by offering its users an alternate user interface, the “Lotus Emulation Interface.” By activating the Emulation Interface, Borland users would see the Lotus menu commands on their screens and could interact with Quattro or Quattro Pro as if using Lotus 1–2–3, albeit with a slightly different looking screen and with many Borland options not available on Lotus 1–2–3. In effect, Borland allowed users to choose how they wanted to communicate with Borland’s spreadsheet programs: either by using menu commands designed by Borland, or by using the commands and command structure used in Lotus 1–2–3 augmented by Borland-added commands.

On July 31, 1992, the district court ruled that the Lotus menu command hierarchy was copyrightable expression because

[a] very satisfactory spreadsheet menu tree can be constructed using different commands and a different command structure from those of Lotus 1–2–3. In fact, Borland has constructed just such [*51]an alternate tree for use in Quattro Pro’s native mode. Even if one holds the arrangement of menu commands constant, it is possible to generate literally millions of satisfactory menu trees by varying the menu commands employed.

The district court demonstrated this by offering alternate command words for the ten commands that appear in Lotus’s main menu. For example, the district court stated that “[t]he ‘Quit’ command could be named ‘Exit’ without any other modifications,” and that “[t]he ‘Copy’ command could be called ‘Clone,’ ‘Ditto,’ ‘Duplicate,’ ‘Imitate,’ ‘Mimic,’ ‘Replicate,’ and ‘Reproduce,’ among others.” Because so many variations were possible, the district court concluded that the Lotus developers’ choice and arrangement of command terms, reflected in the Lotus menu command hierarchy, constituted copyrightable expression.

II.

Discussion

D. The Lotus Menu Command Hierarchy: A “Method of Operation”

Borland argues that the Lotus menu command hierarchy is uncopyrightable because it is a system, method of operation, process, or procedure foreclosed from copyright protection by 17 U.S.C. § 102(b). Section 102(b) states: “In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.” Because we conclude that the Lotus menu command hierarchy is a method of operation, we do not consider whether it could also be a system, process, or procedure.

We think that “method of operation,” as that term is used in § 102(b), refers to the means by which a person operates something, whether it be a car, a food processor, or a computer. Thus a text describing how to operate something would not extend copyright protection to the method of operation itself; other people would be free to employ that method and to describe it in their own words. Similarly, if a new method of operation is used rather than described, other people would still be free to employ or describe that method.

We hold that the Lotus menu command hierarchy is an uncopyrightable “method of operation.” The Lotus menu command hierarchy provides the means by which users control and operate Lotus 1–2–3. If users wish to copy material, for example, they use the “Copy” command. If users wish to print material, they use the “Print” command. Users must use the command terms to tell the computer what to do. Without the menu command hierarchy, users would not be able to access and control, or indeed make use of, Lotus 1–2–3’s functional capabilities.

The Lotus menu command hierarchy does not merely explain and present Lotus 1–2–3’s functional capabilities to the user; it also serves as the method by which the program is operated and controlled. The Lotus menu command hierarchy is The different from the underlying computer code, because while code is necessary for the program to work, its precise formulation is not. In other words, to offer the same capabilities as Lotus 1–2–3, Borland did not have to copy Lotus’s underlying code (and indeed it did not); to allow users to operate its programs in substantially the same way, however, Borland had to copy the Lotus menu command hierarchy. Thus the Lotus 1–2–3 code is not a uncopyrightable “method of operation.”

[*52]The district court held that the Lotus menu command hierarchy, with its specific choice and arrangement of command terms, constituted an “expression” of the “idea” of operating a computer program with commands arranged hierarchically into menus and submenus. Under the district court’s reasoning, Lotus’s decision to employ hierarchically arranged command terms to operate its program could not foreclose its competitors from also employing hierarchically arranged command terms to operate their programs, but it did foreclose them from employing the specific command terms and arrangement that Lotus had used. In effect, the district court limited Lotus 1–2–3’s “method of operation” to an abstraction.

Accepting the district court’s finding that the Lotus developers made some expressive choices in choosing and arranging the Lotus command terms, we nonetheless hold that that expression is not copyrightable because it is part of Lotus 1–2–3’s “method of operation.” We do not think that “methods of operation” are limited to abstractions; rather, they are the means by which a user operates something. If specific words are essential to operating something, then they are part of a “method of operation” and, as such, are unprotectable. This is so whether they must be highlighted, typed in, or even spoken, as computer programs no doubt will soon be controlled by spoken words.

The fact that Lotus developers could have designed the Lotus menu command hierarchy differently is immaterial to the question of whether it is a “method of operation.” In other words, our initial inquiry is not whether the Lotus menu command hierarchy incorporates any expression. Rather, our initial inquiry is whether the Lotus menu command hierarchy is a “method of operation.” Concluding, as we do, that users operate Lotus 1–2–3 by using the Lotus menu command hierarchy, and that the entire Lotus menu command hierarchy is essential to operating Lotus 1–2–3, we do not inquire further whether that method of operation could have been designed differently. The “expressive” choices of what to name the command terms and how to arrange them do not magically change the uncopyrightable menu command hierarchy into copyrightable subject matter.

In many ways, the Lotus menu command hierarchy is like the buttons used to control, say, a video cassette recorder (“VCR”). A VCR is a machine that enables one to watch and record video tapes. Users operate VCRs by pressing a series of buttons that are typically labelled “Record, Play, Reverse, Fast Forward, Pause, Stop/Eject.” That the buttons are arranged and labeled does not make them a “literary work,” nor does it make them an “expression” of the abstract “method of operating” a VCR via a set of labeled buttons. Instead, the buttons are themselves the “method of operating” the VCR.

When a Lotus 1–2–3 user chooses a command, either by highlighting it on the screen or by typing its first letter, he or she effectively pushes a button. Highlighting the “Print” command on the screen, or typing the letter “P,” is analogous to pressing a VCR button labeled “Play.”

Just as one could not operate a buttonless VCR, it would be impossible to operate Lotus 1–2–3 without employing its menu command hierarchy. Thus the Lotus command terms are not equivalent to the labels on the VCR’s buttons, but are instead equivalent to the buttons themselves. Unlike the labels on a VCR’s buttons, which merely make operating a VCR easier by indicating the buttons’ functions, the Lotus menu commands are essential to operating Lotus 1–2–3. Without the menu commands, there would be no way to “push” the Lotus buttons, as one could push unlabeled VCR buttons. While Lotus could probably have designed a user interface for which the command terms were mere labels, it did not do so here. Lotus 1–2–3 depends for its operation on use of the precise command terms that make up the Lotus menu command hierarchy. [*53]

One might argue that the buttons for operating a VCR are not analogous to the commands for operating a computer program because VCRs are not copyrightable, whereas computer programs are. VCRs may not be copyrighted because they do not fit within any of the § 102(a) categories of copyrightable works; the closest they come is “sculptural work.” Sculptural works, however, are subject to a “useful-article” exception whereby “the design of a useful article … shall be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only if, and only to the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. A “useful article” is “an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information.” Whatever expression there may be in the arrangement of the parts of a VCR is not capable of existing separately from the VCR itself, so an ordinary VCR would not be copyrightable.

Computer programs, unlike VCRs, are copyrightable as “literary works.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). Accordingly, one might argue, the “buttons” used to operate a computer program are not like the buttons used to operate a VCR, for they are not subject to a useful-article exception. The response, of course, is that the arrangement of buttons on a VCR would not be copyrightable even without a useful-article exception, because the buttons are an uncopyrightable “method of operation.” Similarly, the “buttons” of a computer program are also an uncopyrightable “method of operation.”

That the Lotus menu command hierarchy is a “method of operation” becomes clearer when one considers program compatibility. Under Lotus’s theory, if a user uses several different programs, he or she must learn how to perform the same operation in a different way for each program used. For example, if the user wanted the computer to print material, then the user would have to learn not just one method of operating the computer such that it prints, but many different methods. We find this absurd. The fact that there may be many different ways to operate a computer program, or even many different ways to operate a computer program using a set of hierarchically arranged command terms, does not make the actual method of operation chosen copyrightable; it still functions as a method for operating the computer and as such is uncopyrightable.

Consider also that users employ the Lotus menu command hierarchy in writing macros. Under the district court’s holding, if the user wrote a macro to shorten the time needed to perform a certain operation in Lotus 1–2–3, the user would be unable to use that macro to shorten the time needed to perform that same operation in another program. Rather, the user would have to rewrite his or her macro using that other program’s menu command hierarchy. This is despite the fact that the macro is clearly the user’s own work product. We think that forcing the user to cause the computer to perform the same operation in a different way ignores Congress’s direction in § 102(b) that “methods of operation” are not copyrightable. That programs can offer users the ability to write macros in many different ways does not change the fact that, once written, the macro allows the user to perform an operation automatically. As the Lotus menu command hierarchy serves as the basis for Lotus 1–2–3 macros, the Lotus menu command hierarchy is a “method of operation.”

We also note that in most contexts, there is no need to “build” upon other people’s expression, for the ideas conveyed by that expression can be conveyed by someone else without copying the first author’s expression. In the context of methods of operation, however, “building” requires the use of the precise method of operation already employed; otherwise, “building” would require dismantling, too. Original developers are [*54]not the only people entitled to build on the methods of operation they create; anyone can. Thus, Borland may build on the method of operation that Lotus designed and may use the Lotus menu command hierarchy in doing so.

Reversed.

BOUDIN, Circuit Judge, concurring.

Most of the law of copyright and the “tools” of analysis have developed in the context of literary works such as novels, plays, and films. In this milieu, the principal problem—simply stated, if difficult to resolve—is to stimulate creative expression without unduly limiting access by others to the broader themes and concepts deployed by the author. The middle of the spectrum presents close cases; but a “mistake” in providing too much protection involves a small cost: subsequent authors treating the same themes must take a few more steps away from the original expression.

The problem presented by computer programs is fundamentally different in one respect. The computer program is a means for causing something to happen; it has a mechanical utility, an instrumental role, in accomplishing the world’s work. Granting protection, in other words, can have some of the consequences of patent protection in limiting other people’s ability to perform a task in the most efficient manner. Utility does not bar copyright (dictionaries may be copyrighted), but it alters the calculus.

Of course, the argument for protection is undiminished, perhaps even enhanced, by utility: if we want more of an intellectual product, a temporary monopoly for the creator provides incentives for others to create other, different items in this class. But the “cost” side of the equation may be different where one places a very high value on public access to a useful innovation that may be the most efficient means of performing a given task. Thus, the argument for extending protection may be the same; but the stakes on the other side are much higher.

Requests for the protection of computer menus present the concern with fencing off access to the commons in an acute form. A new menu may be a creative work, but over time its importance may come to reside more in the investment that has been made by users in learning the menu and in building their own mini-programs—macros—in reliance upon the menu. Better typewriter keyboard layouts may exist, but the familiar QWERTY keyboard dominates the market because that is what everyone has learned to use. The QWERTY keyboard is nothing other than a menu of letters.

Thus, to assume that computer programs are just one more new means of expression, like a filmed play, may be quite wrong. The “form”—the written source code or the menu structure depicted on the screen—look hauntingly like the familiar stuff of copyright; but the “substance” probably has more to do with problems presented in patent law or, as already noted, in those rare cases where copyright law has confronted industrially useful expressions. Applying copyright law to computer programs is like assembling a jigsaw puzzle whose pieces do not quite fit. [*55]

__________

Check Your Understanding – Lotus

Question 1. What did Borland copy from Lotus 1-2-3?

Question 2. Why did the First Circuit hold that Lotus’s copyright in Lotus 1–2–3 was not infringed when Borland copied the Lotus 1–2–3 menu command hierarchy into its competing computer spreadsheet programs?

Question 3. True or false: The First Circuit opined that it could have, in the alternative, found the Lotus menu command hierarchy to be uncopyrightable under the “useful article exception.”

B. Merger and Thin Protection

What happens when there is only one means of expressing an idea, such that it would be impossible to grant the author an exclusive right in her expression of the idea without at the same time giving her an exclusive right in the underlying idea? Under the doctrine of merger, courts have held that when there is only one way, or a very small number of ways, to express an idea, then that expression cannot be copyrighted. To allow copyright on the expression would unduly restrict access to the underlying idea, and thus as a matter of policy the courts will invoke the merger doctrine to deny copyright protection to any expression of the idea.

Closely related to the doctrine of merger is the doctrine of thin copyright protection. Courts will afford thin copyright protection to the expression of an idea when there are only a limited number of ways of expressing the idea. The difference between merger and thin protection is that merger applies when there are only a very small number of ways (perhaps only one way) of expressing an idea, and results in a denial of copyright protection altogether. Thin protection occurs when there are enough different ways to [*56] express the idea that merger does not apply, but still the number of different ways of expressing the idea is sufficiently limited that “thicker” protection of the expression would threaten to unduly tie up the idea itself. When a court says that it will afford a copyrighted work only thin protection, what it means is that it will only find infringement by an unauthorized copy of the work that is identical, or at least very nearly identical, to the copyrighted work.

As stated by Judge Kozinski:

If there’s a wide range of expression (for example, there are gazillions of ways to make an aliens-attack movie), then copyright protection is “broad” [editor’s note, i.e., “thick”] and a work will infringe if it’s “substantially similar” to the copyrighted work. If there’s only a narrow range of expression (for example, there are only so many ways to paint a red bouncy ball on blank canvas), then copyright protection is “thin” and a work must be “virtually identical” to infringe.[5]

Some examples help illustrate this principle. A book in the Harry Potter series would receive relatively thick/broad protection, since there are a vast number of different ways of expressing the underlying ideas in these books, e.g., a school for young wizards and witches. The copyright in a Harry Potter book could be infringed by another book that is quite different in the details, but nonetheless deemed substantially similar by a court. This would be an example of non-literal infringement, which is discussed later in this casebook, along with the “substantial similarity” standard used in assessing copyright infringement.

On the other hand, a copyrighted database of factual information will typically be afforded only thin protection, if a court concludes that there are only a limited number of ways of expressing the underlying idea, i.e., the factual information. As a consequence of thin protection, a court would only find the copyrighted database to be infringed by a database presenting the factual information in an identical (or near identical) manner. This is basically the scenario invoked by the Supreme Court in Feist, which the reader is encouraged to revisit at this point to review the Supreme Court’s discussion of thin protection in that case. Other examples of subject matter likely to be afforded thin protection would be a recipe or the rules for a contest.

The doctrines of thin protection and merger, and their role in enforcing the idea-expression dichotomy, are illustrated in the following cases.

__________

Some things to consider when reading Morrissey:

- The court’s invocation of the idea-expression dichotomy to find that the plaintiff’s description of the rules of its “sweepstakes” contest is not copyrightable. The court does not use the word “idea,” but that is what it is getting at when it holds that the “substance” of the contest is not copyrightable.

- Although the court does not use the word “thin” protection, that is what it’s getting at when it refers to “the principle of a stringent standard for showing infringement which some courts apply when the subject matter involved admits of little variation in form of expression.”

- The court does not use the word “merger,” but that was the basis of its decision, and to this day Morrissey is considered to be one of the seminal examples of a court applying the merger doctrine. Take note of the court’s discussion of the policy underlying the merger doctrine.

[*57]Morrissey v. Procter & Gamble Co.

379 F.2d 675 (1st Cir. 1967)

ALDRICH, Chief Judge.

This is an appeal from a summary judgment for the defendant. The plaintiff, Morrissey, is the copyright owner of a set of rules for a sales promotional contest of the ‘sweepstakes’ type involving the social security numbers of the participants. Plaintiff alleges that the defendant, Procter & Gamble Company, infringed, by copying, almost precisely, Rule 1. In its motion for summary judgment defendant denies that plaintiff’s Rule 1 is copyrightable material. The district court held for the defendant.

[As a preliminary matter,] we recite plaintiff’s Rule 1, and defendant’s Rule 1, the italicizing in the latter being ours to note the defendant’s variations or changes.

Plaintiff’s Rule:

1. Entrants should print name, address and social security number on a boxtop, or a plain paper. Entries must be accompanied by * * * boxtop or by plain paper on which the name * * * is copied from any source. Official rules are explained on * * * packages or leaflets obtained from dealer. If you do not have a social security number you may use the name and number of any member of your immediate family living with you. Only the person named on the entry will be deemed an entrant and may qualify for prize.

Use the correct social security number belonging to the person named on entry * * * wrong number will be disqualified.

Defendant’s Rule:

1. Entrants should print name, address and Social Security number on a Tide boxtop, or on (a) plain paper. Entries must be accompanied by Tide boxtop (any size) or by plain paper on which the name ‘Tide’ is copied from any source. Official rules are available on Tide Sweepstakes packages, or on leaflets at Tide dealers, or you can send a stamped, self-addressed envelope to: Tide ‘Shopping Fling’ Sweepstakes, P.O. Box 4459, Chicago 77, Illinois.

If you do not have a Social Security number, you may use the name and number of any member of your immediate family living with you. Only the person named on the entry will be deemed an entrant and may qualify for a prize.

Use the correct Social Security number, belonging to the person named on the entry- wrong numbers will be disqualified.

The district court took the position that since the substance of the contest was not copyrightable, which is unquestionably correct, Baker v. Selden, 101 U.S. 99 (1879), and the substance was relatively simple, it must follow that plaintiff’s rule sprung directly from the substance and ‘contains no original creative authorship.’ This does not follow. Copyright attaches to form of expression, and defendant’s own proof established that [*58]there was more than one way of expressing even this simple substance. Nor, in view of the almost precise similarity of the two rules, could defendant successfully invoke the principle of a stringent standard for showing infringement which some courts apply when the subject matter involved admits of little variation in form of expression.[6]

Nonetheless, we must hold for the defendant. When the uncopyrightable subject matter is very narrow, so that the topic necessarily requires, if not only one form of expression, at best only a limited number, to permit copyrighting would mean that a party or parties, by copyrighting a mere handful of forms, could exhaust all possibilities of future use of the substance. In such circumstances it does not seem accurate to say that any particular form of expression comes from the subject matter. However, it is necessary to say that the subject matter would be appropriated by permitting the copyrighting of its expression. We cannot recognize copyright as a game of chess in which the public can be checkmated.

Upon examination the matters embraced in Rule 1 are so straightforward and simple that we find this limiting principle to be applicable. Furthermore, its operation need not await an attempt to copyright all possible forms. It cannot be only the last form of expression which is to be condemned, as completing defendant’s exclusion from the substance. Rather, in these circumstances, we hold that copyright does not extend to the subject matter at all, and plaintiff cannot complain even if his particular expression was deliberately adopted.

Affirmed.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Morrissey

Question 1. The defendant in Morrissey prevailed by successfully invoking this doctrine of copyright law.

Some things to consider when reading Satava:

- The court’s invocation of the idea-expression dichotomy to find that the plaintiff’s jellyfish sculptures are only eligible for thin copyright protection.

- The court’s discussion of the “standard elements,” or “scenes a faire” doctrine.

- The basis of the court’s determination of non-infringement.

- How valuable the thin copyright protection afforded to the sculptures by the court is, and whether it restricts others from creating similar sculptures. [*59]

Satava v. Lowry

323 F.3d 805 (9th Cir. 2003)

GOULD, Circuit Judge.

In the Copyright Act, Congress sought to benefit the public by encouraging artists’ creative expression. Congress carefully drew the contours of copyright protection to achieve this goal. It granted artists the exclusive right to the original expression in their works, thereby giving them a financial incentive to create works to enrich our culture. But it denied artists the exclusive right to ideas and standard elements in their works, thereby preventing them from monopolizing what rightfully belongs to the public. In this case, we must locate the faint line between unprotected idea and original expression in the context of realistic animal sculpture. We must decide whether an artist’s lifelike glass-in-glass sculptures of jellyfish are protectable by copyright. Because we conclude that the sculptures are composed of unprotectable ideas and standard elements, and also that the combination of those unprotectable elements is unprotectable, we reverse the judgment of the district court.

I

Plaintiff Richard Satava is a glass artist from California. In the late 1980s, Satava was inspired by the jellyfish display at an aquarium. He began experimenting with jellyfish sculptures in the glass-in-glass medium and, in 1990, began selling glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures. The sculptures sold well, and Satava made more of them. By 2002, Satava was designing and creating about three hundred jellyfish sculptures each month. Satava’s sculptures are sold in galleries and gift shops in forty states, and they sell for hundreds or thousands of dollars, depending on size. Satava has registered several of his works with the Register of Copyrights.

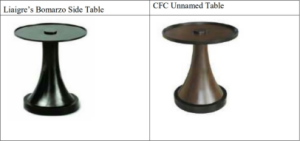

Satava describes his sculptures as “vertically oriented, colorful, fanciful jellyfish with tendril-like tentacles and a rounded bell encased in an outer layer of rounded clear glass that is bulbous at the top and tapering toward the bottom to form roughly a bullet shape, with the jellyfish portion of the sculpture filling almost the entire volume of the outer, clearglass shroud.” Satava’s jellyfish appear lifelike. They resemble the pelagia colorata that live in the Pacific Ocean:[*60]

During the 1990s, defendant Christopher Lowry, a glass artist from Hawaii, also began making glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures. Lowry’s sculptures look like Satava’s, and many people confuse them:[*61]

In Hawaii, Satava’s sculptures have appeared in tourist brochures and art magazines. The sculptures are sold in sixteen galleries and gift shops, and they appear in many store windows. Lowry admits he saw a picture of Satava’s jellyfish sculptures in American Craft magazine in 1996. And he admits he examined a Satava jellyfish sculpture that a customer brought him for repair in 1997.

Glass-in-glass sculpture is a centuries-old art form that consists of a glass sculpture inside a second glass layer, commonly called the shroud. The artist creates an inner glass sculpture and then dips it into molten glass, encasing it in a solid outer glass shroud. The shroud is malleable before it cools, and the artist can manipulate it into any shape he or she desires.

Satava filed suit against Lowry accusing him of copyright infringement. Satava requested, and the district court granted, a preliminary injunction, enjoining Lowry from making sculptures that resemble Satava’s. Lowry appealed to us.

II

We hold that the district court based its decision on an erroneous legal standard, so we reverse.

Copyright protection is available for “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). Copyright protection does not, however, “extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery….” 17 U.S.C. § 102(b).

[*62]Any copyrighted expression must be “original.” Feist Pubs., Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 345 (1991). The originality requirement mandates that objective “facts” and ideas are not copyrightable. Similarly, expressions that are standard, stock, or common to a particular subject matter or medium are not protectable under copyright law.[7]

It follows from these principles that no copyright protection may be afforded to the idea of producing a glass-in-glass jellyfish sculpture or to elements of expression that naturally follow from the idea of such a sculpture. See Aliotti v. R. Dakin & Co., 831 F.2d 898, 901 (9th Cir.1987) (“No copyright protection may be afforded to the idea of producing stuffed dinosaur toys or to elements of expression that necessarily follow from the idea of such dolls.”). Satava may not prevent others from copying aspects of his sculptures resulting from either jellyfish physiology or from their depiction in the glass-in-glass medium.

Satava may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish with tendril-like tentacles or rounded bells, because many jellyfish possess those body parts. He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish in bright colors, because many jellyfish are brightly colored. He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish swimming vertically, because jellyfish swim vertically in nature and often are depicted swimming vertically. See id. at 901 n. 1 (noting that a Tyrannosaurus stuffed animal’s open mouth was not an element protected by copyright because Tyrannosaurus “was a carnivore and is commonly pictured with its mouth open”).

Satava may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish within a clear outer layer of glass, because clear glass is the most appropriate setting for an aquatic animal. See id. (noting that a Pterodactyl stuffed animal’s depiction as a mobile hanging from the ceiling was not protectable because Pterodactyl “was a winged creature and thus is appropriate for such treatment”). He may not prevent others from depicting jellyfish “almost filling the entire volume” of the outer glass shroud, because such proportion is standard in glass-in-glass sculpture. And he may not prevent others from tapering the shape of their shrouds, because that shape is standard in glass-in-glass sculpture.

Satava’s glass-in-glass jellyfish sculptures, though beautiful, combine several unprotectable ideas and standard elements. These elements are part of the public domain. They are the common property of all, and Satava may not use copyright law to seize them for his exclusive use.

It is true, of course, that a combination of unprotectable elements may qualify for copyright protection. But it is not true that any combination of unprotectable elements automatically qualifies for copyright protection. Our case law suggests, and we hold today, that a combination of unprotectable elements is eligible for copyright protection only if those elements are numerous enough and their selection and arrangement original enough that their combination constitutes an original work of authorship.

The combination of unprotectable elements in Satava’s sculpture falls short of this standard. The selection of the clear glass, oblong shroud, bright colors, proportion, vertical orientation, and stereotyped jellyfish form, considered together, lacks the quantum of originality needed to merit copyright protection. These elements are so commonplace in glass-in-glass sculpture and so typical of jellyfish physiology that to recognize copyright protection in their combination effectively would give Satava a monopoly on lifelike glass-in-glass sculptures of single jellyfish with vertical tentacles. Because the quantum of originality Satava added in combining these standard and stereotyped elements must be considered “trivial” under our case law, Satava cannot prevent other artists from combining them. [*63]

We do not mean to suggest that Satava has added nothing copyrightable to his jellyfish sculptures. He has made some copyrightable contributions: the distinctive curls of particular tendrils; the arrangement of certain hues; the unique shape of jellyfishes’ bells. To the extent that these and other artistic choices were not governed by jellyfish physiology or the glass-in-glass medium, they are original elements that Satava theoretically may protect through copyright law. Satava’s copyright on these original elements (or their combination) is “thin,” however, comprising no more than his original contribution to ideas already in the public domain. Stated another way, Satava may prevent others from copying the original features he contributed, but he may not prevent others from copying elements of expression that nature displays for all observers, or that the glass-in-glass medium suggests to all sculptors. Satava possesses a thin copyright that protects against only virtually identical copying.

We do not hold that realistic depictions of live animals cannot be protected by copyright. We recognize, however, that the scope of copyright protection in such works is narrow. Nature gives us ideas of animals in their natural surroundings: an eagle with talons extended to snatch a mouse; a grizzly bear clutching a salmon between its teeth; a butterfly emerging from its cocoon; a wolf howling at the full moon; a jellyfish swimming through tropical waters. These ideas, first expressed by nature, are the common heritage of humankind, and no artist may use copyright law to prevent others from depicting them.

An artist may, however, protect the original expression he or she contributes to these ideas. An artist may vary the pose, attitude, gesture, muscle structure, facial expression, coat, or texture of animal. An artist may vary the background, lighting, or perspective. Such variations, if original, may earn copyright protection. Because Satava’s jellyfish sculptures contain few variations of this type, the scope of his copyright is narrow.

We do not mean to short-change the legitimate need of creative artists to protect their original works. After all, copyright law achieves its high purpose of enriching our culture by giving artists a financial incentive to create. But we must be careful in copyright cases not to cheat the public domain. Only by vigorously policing the line between idea and expression can we ensure both that artists receive due reward for their original creations and that proper latitude is granted other artists to make use of ideas that properly belong to us all.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Satava

Question 1. True or false: The court’s decision in Satava leaves the plaintiff with no copyright protection for his sculptures.

Some things to consider when reading Silvertop Assocs.:

- [*64]This decision applies the “merger” and “scenes a faire” doctrines to a full-body banana costume.

- Other aspects of this decision addressing the useful article doctrine appear later in this casebook.

Silvertop Assocs. Inc. v. Kangaroo Mfg. Inc.

931 F.3d 215 (3d Cir. 2019)

HARDIMAN, Circuit Judge.

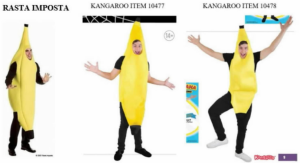

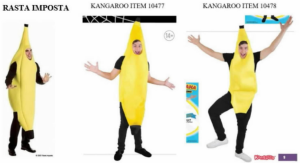

This interlocutory appeal involves the validity of a copyright in a full-body banana costume. Appellant Kangaroo Manufacturing Inc. concedes that the banana costume it manufactures and sells is substantially similar to the banana costume created and sold by Appellee Rasta Imposta. See infra Appendix A. We hold that, in combination, the Rasta costume’s non-utilitarian, sculptural features are copyrightable.

* * *

Kangaroo invokes two copyright doctrines—merger and scenes a faire—to argue the banana costume is ineligible for protection. Both arguments address the same question: whether copyrighting the banana costume would effectively monopolize an underlying idea, either directly or through elements necessary to that idea’s expression.

Because Congress has excluded “any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery” from copyright protection, 17 U.S.C. § 102(b), courts deny such protection when a work’s underlying idea can effectively be expressed in only one way. Courts term this rare occurrence “merger,” and find it only when “there are no or few other ways of expressing a particular idea.”

Here, copyrighting Rasta’s banana costume would not effectively monopolize the underlying idea because there are many other ways to make a costume resemble a banana. Indeed, Rasta provided over 20 non-infringing examples. As the District Court observed, one can easily distinguish those examples from Rasta’s costume based on the shape, curvature, tips, tips’ color, overall color, length, width, lining, texture, and material. We agree and hold the merger doctrine does not apply here.

Courts also exclude scenes a faire from copyright protection, which include elements standard, stock, or common to a particular topic or that necessarily follow from a common theme or setting. The doctrine covers those elements of a work that necessarily result from external factors inherent in the subject matter of the work.” As with merger, the scenes a faire doctrine seeks to curb copyright’s potential to allow monopolizing an underlying idea—via features that are so common or necessary to that idea’s expression that copyrighting them effectively copyrights the idea itself. E.g., Mitel, 124 F.3d 1366, 1374–75 (10th Cir. 1997)(citing foot chases as a scene a faire of police fiction).

Here too, copyrighting the banana costume’s non-utilitarian features in combination would not threaten such monopolization. Kangaroo points to no specific feature that necessarily results from the costume’s subject matter (a banana). Although a banana costume is likely to be yellow, it could be any shade of yellow—or green or brown for that matter. Although a banana costume is likely to be curved, it need not be—let alone in any particular manner. And although a banana costume is likely to have ends that resemble [*65] a natural banana’s, those tips need not look like Rasta’s black tips (in color, shape, or size). Again, the record includes over 20 examples of banana costumes that Rasta concedes would be non-infringing. The scenes a faire doctrine does not apply here either.

* * *

Because Rasta established a reasonable likelihood that it could prove entitlement to protection for the veritable fruits of its intellectual labor, we will affirm.

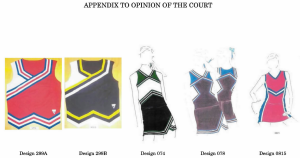

APPENDIX A

__________

Check Your Understanding – Silvertop Assocs.

Socratic Script

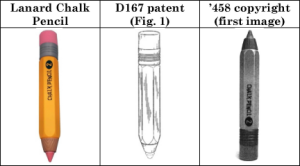

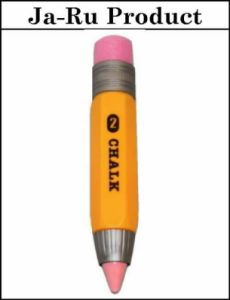

How was the idea-expression dichotomy applied by the courts in Silvertop Assocs. and Lanard Toys to arrive at the opposite result with respect to separability?

[*66]Can you rationalize the divergent outcomes with respect to the copyrightability of a banana-shaped costume versus a pencil-shaped chalk holder?

Some things to consider when reading CDN:

- This case appeared earlier in the book in the section on originality. In the part of the decision excerpted below, the court finds that merger does not preclude copyright protection for CDN’s wholesale coin prices.

- What does the court identify as the idea in this case? And what does it identify as the expression?

CDN Inc. v. Kapes

197 F.3d 1256 (9th Cir. 1999)

O’SCANNLAIN, Circuit Judge.

[Editor’s note: The facts of this case, and the court’s decision finding CDN’s wholesale coin prices copyrightable, appear earlier in this casebook.]

IV

In his defense, Kapes argues that a price is an idea of the value of the product, which can be expressed only using a number. Thus the idea and the expression merge and neither qualifies for copyright protection. This is the doctrine of merger. In order to protect the free exchange of ideas, courts have long held that when expression is essential to conveying the idea, expression will also be unprotected. But accepting the principle in all cases, including on these facts, would eviscerate the protection of the copyright law. Cf. CCC, 44 F.3d at 70 (noting that every compilation represents an idea, which in order to be conveyed accurately must be conveyed only by its expression).

Conceptually, the problem arises because the critical distinction between “idea” and “expression” is difficult to draw. We have endorsed Judge Hand’s abstractions formulation laid out in Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp., 45 F.2d 119, 121 (2d Cir.1930). The formulation recognizes that every work can be described at varying levels of abstraction, and the higher the level of abstraction copied, the less likely this taking will be infringement of a copyright.

As Judge Hand noted, the difference between idea and expression is one of degree. This circuit has held that “[t]he guiding consideration in drawing the line is the preservation of the balance between competition [*67] and protection reflected in the patent and copyright laws.” Rosenthal, 446 F.2d at 742. In this case, the prices fall on the expression side of the line. CDN does not, nor could it, claim protection for its idea of creating a wholesale price guide, but it can use the copyright laws to protect its idea of what those prices are. Drawing this line preserves the balance between competition and protection: it allows CDN’s competitors to create their own price guides and thus furthers competition, but protects CDN’s creation, thus giving it an incentive to create such a guide. The doctrine of merger does not bar copyright protection in this case.

__________

Check Your Understanding – CDN

Question 1. In the excerpt from CDN provided above, what rationale did the court provide for its rejection of the defendant’s argument that the plaintiff’s wholesale coin prices constituted “ideas,” as opposed to the expression of those ideas?

Some things to consider when reading Kregos:

- The fact that Kregos is not asserting copyright protection of the actual statistics, but rather “the particular selection of categories of statistics appearing on his form.”

- The court’s application of Feist to Krego’s pitching forms, and the question of whether the plaintiff’s selection of categories of baseball statistics was sufficiently original. Feist came out shortly before Kregos was decided.

- The court’s comparison of the facts in this case with the Second Circuit’s earlier decisions in Eckes and FII.

- The significance of the fact that the district court decided the case on a motion for summary judgment.

- The court’s application of Judge Hand’s “abstractions test” from Nichols, and the significance of the judges’ different definitions of the “idea” of the pitching forms.

- The fact that the case ultimately hinges on the judges’ determination of where to draw the line between idea and expression when the purported copyright is based on the author’s selection and arrangement of facts.

- The significance of the court’s observation that Kregos “does not present his selection of nine statistics as a method of predicting the outcome of baseball games.”

- The court’s discussion of “the continuum spanning matters of pure taste to matters of predictive analysis,” and the potential policy concerns raised by the hypothetical “doctor who publishes a list of symptoms that he believes provides a helpful diagnosis of a disease. [*68]”

- Although the court does not use the term “thin protection,” that is what it is getting at in subsection I.D, i.e., “Extent of Protection.”

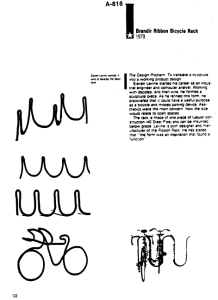

- An example of one of the plaintiff’s baseball pitching forms, taken from an appendix of the district court decision, is presented below.

Kregos v. Associated Press

937 F.2d 700 (2d Cir. 1991)

JON O. NEWMAN, Circuit Judge:

The primary issue on this appeal is whether the creator of a baseball pitching form is entitled to a copyright. [*69] The appeal requires us to consider the extent to which the copyright law protects a compiler of information. George L. Kregos appeals from the April 30, 1990, judgment of the District Court for the Southern District of New York (Gerard L. Goettel, Judge) dismissing on motion for summary judgment his copyright claims against the Associated Press (“AP”) and Sports Features Syndicate, Inc. (“Sports Features”). We conclude that Kregos is entitled to a trial on his copyright claim, though the available relief may be extremely limited.

Facts

The facts are fully set forth in Judge Goettel’s thorough opinion, 731 F.Supp. 113 (S.D.N.Y.1990). The reader’s attention is particularly called to the appendices to that opinion, which set forth Kregos’ pitching form and the allegedly infringing forms. Id. at 122–24 (Appx. 1–4). Kregos distributes to newspapers a pitching form, discussed in detail below, that displays information concerning the past performances of the opposing pitchers scheduled to start each day’s baseball games. The form at issue in this case, first distributed in 1983, is a redesign of an earlier form developed by Kregos in the 1970’s. Kregos registered his form with the Copyright Office and obtained a copyright. Though the form, as distributed to subscribing newspapers, includes statistics, the controversy in this case concerns only Kregos’ rights to the form without each day’s data, in other words, his rights to the particular selection of categories of statistics appearing on his form.

In 1984, AP began publishing a pitching form provided by Sports Features. The AP’s 1984 form was virtually identical to Kregos’ 1983 form. AP and Sports Features changed their form in 1986 in certain respects, which are discussed in part I(d) below.

Kregos’ 1983 form lists four items of information about each day’s games—the teams, the starting pitchers, the game time, and the betting odds, and then lists nine items of information about each pitcher’s past performance, grouped into three categories. Since there can be no claim of a protectable interest in the categories of information concerning each day’s game, we confine our attention to the categories of information concerning the pitchers’ past performances. For convenience, we will identify each performance item by a number from 1 to 9 and use that number whenever referring to the same item in someone else’s form.

The first category in Kregos’ 1983 form, performance during the entire season, comprises two items—won/lost record (1) and earned run average (2). The second category, performance during the entire season against the opposing team at the site of the game, comprises three items—won/lost record (3), innings pitched (4), and earned run average (5). The third category, performance in the last three starts, comprises four items—won/lost record (6), innings pitched (7), earned run average (8), and men on base average (9). This last item is the average total of hits and walks given up by a pitcher per nine innings of pitching.

It is undisputed that prior to Kregos’ 1983 form, no form had listed the same nine items collected in his form. It is also undisputed that some but not all of the nine items of information had previously appeared in other forms.