Chapter 12: Fair Use

[*473] Section 106, which sets forth the exclusive rights of copyright owners, specifically provides that these rights are “[s]ubject to sections 107 through 122” of the Act, which set forth various limitations and defenses to an assertion of copyright infringement.

Perhaps the most significant of these limitations, and certainly the most litigated, is the fair use defense as provided for in § 107 of the Act:

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include —

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

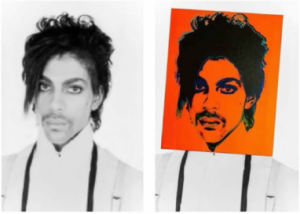

In assessing fair use, courts rely heavily on the four factors set forth in the statute. The first and fourth factors tend to be the most important considerations, while the courts often downplay the role of the second factor. In assessing the first factor, courts often focus on the “transformativeness” of the accused use, whether that use was commercial in nature, and whether the use was educational or in furtherance of some other social benefit. The fourth factor considers harm to the market for both the original work and derivative versions of the original, an issue addressed in the most recent Supreme Court decision addressing fair use, Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (excerpted below).

In Eldred v. Ashcroft, a Supreme Court decision that appeared earlier in this casebook, Justice Ginsburg referred to fair use as a “built-in … safeguard” of the principles of free speech enshrined in the First Amendment.[1] She notes that the fair use defense allows the public to use not only facts and ideas contained in a copyrighted work, but also expression itself in certain circumstances, and affords considerable “latitude for scholarship and comment.”

The following cases analyze the fair use defense in a variety of contexts. When reading these cases you might find the outcomes variable, if not outright inconsistent. You are not alone—fair use is a notoriously [*474] hazy area of the law. Professor Paul Goldstein has described fair use as “the great white whale of American copyright law. Enthralling, enigmatic, protean, it endlessly fascinates us even as it defeats our every attempt to subdue it.”[2] Your goal at this point is to recognize the main doctrines and arguments that come into play when the court addresses an accused infringer’s assertion of fair use.

Some things to consider when reading Campbell:

- The case arose out of the rap group 2 Live Crew’s decision to release an unauthorized, arguably parodic version of the famous 1960s rock ballad Oh, Pretty Woman. 2 Live Crew argued that its use was fair use. The Sixth Circuit held that it was not fair use, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari.

- What was the error the Sixth Circuit made, according to the Supreme Court?

- Note the Court’s emphasis on the first fair use factor, particularly the importance of whether a use is transformative. Once the Court found transformativeness, did it effectively render the other factors irrelevant?

- Understand the distinction between satire and parody, as explained by the Court, and why it matters in terms of the first fair use factor.

- Understand the distinction between a parodic and nonparodic rap version of Oh, Pretty Woman, and why it matters for purposes of the fourth fair use factor.

- In applying factor 4, the Court investigates “market substitution.” Which markets are relevant to this analysis?

- For close to 30 years, Campbell constituted the Supreme Court’s last word on fair use, and has been a very influential decision. The fair use landscape has shifted somewhat recently, thanks to Supreme Court decisions addressing fair use in 2021 and 2023, Google v. Oracle and Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, both of which appear later in this section of the casebook.

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.

510 U.S. 569 (1994)

Justice SOUTER delivered the opinion of the Court.

We are called upon to decide whether 2 Live Crew’s commercial parody of Roy Orbison’s song, “Oh, Pretty Woman,” may be a fair use within the meaning of the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 107. Although the District Court granted summary judgment for 2 Live Crew, the Court of Appeals reversed, holding the defense of fair use barred by the song’s commercial character and excessive borrowing. Because we hold that a parody’s commercial character is only one element to be weighed in a fair use enquiry, and that insufficient consideration was given to the nature of parody in weighing the degree of copying, we reverse and remand.

I

[*475] In 1964, Roy Orbison and William Dees wrote a rock ballad called “Oh, Pretty Woman” and assigned their rights in it to respondent Acuff–Rose Music, Inc. Acuff–Rose registered the song for copyright protection.

Petitioners Luther R. Campbell, Christopher Wongwon, Mark Ross, and David Hobbs are collectively known as 2 Live Crew, a popular rap music group. In 1989, Campbell wrote a song entitled “Pretty Woman,” which he later described in an affidavit as intended, “through comical lyrics, to satirize the original work….” On July 5, 1989, 2 Live Crew’s manager informed Acuff–Rose that 2 Live Crew had written a parody of “Oh, Pretty Woman,” that they would afford all credit for ownership and authorship of the original song to Acuff–Rose, Dees, and Orbison, and that they were willing to pay a fee for the use they wished to make of it. Enclosed with the letter were a copy of the lyrics and a recording of 2 Live Crew’s song.–Rose’s agent refused permission, stating that “I am aware of the success enjoyed by ‘The 2 Live Crews’, but I must inform you that we cannot permit the use of a parody of ‘Oh, Pretty Woman.’” Nonetheless, in June or July 1989, 2 Live Crew released records, cassette tapes, and compact discs of “Pretty Woman” in a collection of songs entitled “As Clean As They Wanna Be.” The albums and compact discs identify the authors of “Pretty Woman” as Orbison and Dees and its publisher as Acuff–Rose.

Almost a year later, after nearly a quarter of a million copies of the recording had been sold, Acuff–Rose sued 2 Live Crew and its record company, Luke Skyywalker Records, for copyright infringement. The District Court granted summary judgment for 2 Live Crew, reasoning that the commercial purpose of 2 Live Crew’s song was no bar to fair use; that 2 Live Crew’s version was a parody, which “quickly degenerates into a play on words, substituting predictable lyrics with shocking ones” to show “how bland and banal the Orbison song” is; that 2 Live Crew had taken no more than was necessary to “conjure up” the original in order to parody it; and that it was “extremely unlikely that 2 Live Crew’s song could adversely affect the market for the original.” The District Court weighed these factors and held that 2 Live Crew’s song made fair use of Orbison’s original.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed and remanded. Although it assumed for the purpose of its opinion that 2 Live Crew’s song was a parody of the Orbison original, the Court of Appeals thought the District Court had put too little emphasis on the fact that “every commercial use … is presumptively … unfair,” Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984), and it held that “the admittedly commercial nature” of the parody “requires the conclusion” that the first of four factors relevant under the statute weighs against a finding of fair use. Next, the Court of Appeals determined that, by “taking the heart of the original and making it the heart of a new work,” 2 Live Crew had, qualitatively, taken too much. Finally, after noting that the effect on the potential market for the original (and the market for derivative works) is “undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use,” Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985), the Court of Appeals faulted the District Court for “refus[ing] to indulge the presumption” that “harm for purposes of the fair use analysis has been established by the presumption attaching to commercial uses.” In sum, the court concluded that its “blatantly commercial purpose … prevents this parody from being a fair use.”

We granted certiorari, to determine whether 2 Live Crew’s commercial parody could be a fair use.

II

It is uncontested here that 2 Live Crew’s song would be an infringement of Acuff–Rose’s rights in “Oh, Pretty [*476] Woman,” under the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 106, but for a finding of fair use through parody.[3] From the infancy of copyright protection, some opportunity for fair use of copyrighted materials has been thought necessary to fulfill copyright’s very purpose, “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts….” U.S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

In Folsom v. Marsh, Justice Story distilled the essence of law and methodology from the earlier cases: “look to the nature and objects of the selections made, the quantity and value of the materials used, and the degree in which the use may prejudice the sale, or diminish the profits, or supersede the objects, of the original work.” Thus expressed, fair use remained exclusively judge-made doctrine until the passage of the 1976 Copyright Act, in which Justice Story’s summary is discernible:

Ҥ 107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

Congress meant § 107 to restate the present judicial doctrine of fair use, not to change, narrow, or enlarge it in any way and intended that courts continue the common-law tradition of fair use adjudication. The fair use doctrine thus permits and requires courts to avoid rigid application of the copyright statute when, on occasion, it would stifle the very creativity which that law is designed to foster.

The task is not to be simplified with bright-line rules, for the statute, like the doctrine it recognizes, calls for case-by-case analysis.

A

The first factor in a fair use enquiry is “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.” The enquiry here may be guided by the examples given in the preamble to § 107, looking to whether the use is for criticism, or comment, or news reporting, and the like. The central purpose of this investigation is to see, in Justice Story’s words, whether [*477] the new work merely “supersede[s] the objects” of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is “transformative.” Although such transformative use is not absolutely necessary for a finding of fair use, the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works. Such works thus lie at the heart of the fair use doctrine’s guarantee of breathing space within the confines of copyright, and the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.

Parody has an obvious claim to transformative value, as Acuff–Rose itself does not deny. Like less ostensibly humorous forms of criticism, it can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one. Parody like other comment or criticism, may claim fair use under § 107.

Modern dictionaries describe a parody as a “literary or artistic work that imitates the characteristic style of an author or a work for comic effect or ridicule,” or as a “composition in prose or verse in which the characteristic turns of thought and phrase in an author or class of authors are imitated in such a way as to make them appear ridiculous.” For the purposes of copyright law, the nub of the definitions, and the heart of any parodist’s claim to quote from existing material, is the use of some elements of a prior author’s composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author’s works. If, on the contrary, the commentary has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, which the alleged infringer merely uses to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh, the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish), and other factors, like the extent of its commerciality, loom larger. Parody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s (or collective victims’) imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.

The fact that parody can claim legitimacy for some appropriation does not, of course, tell either parodist or judge much about where to draw the line. Like a book review quoting the copyrighted material criticized, parody may or may not be fair use, and petitioners’ suggestion that any parodic use is presumptively fair has no more justification in law or fact than the equally hopeful claim that any use for news reporting should be presumed fair .The Act has no hint of an evidentiary preference for parodists over their victims, and no workable presumption for parody could take account of the fact that parody often shades into satire when society is lampooned through its creative artifacts, or that a work may contain both parodic and nonparodic elements. Accordingly, parody, like any other use, has to work its way through the relevant factors, and be judged case by case, in light of the ends of the copyright law.

Here, the District Court held, and the Court of Appeals assumed, that 2 Live Crew’s “Pretty Woman” contains parody, commenting on and criticizing the original work, whatever it may have to say about society at large. As the District Court remarked, the words of 2 Live Crew’s song copy the original’s first line, but then quickly degenerate into a play on words, substituting predictable lyrics with shocking ones that derisively demonstrate how bland and banal the Orbison song seems to them. Judge Nelson, dissenting below, came to the same conclusion, that the 2 Live Crew song was clearly intended to ridicule the white-bread original and reminds us that sexual congress with nameless streetwalkers is not necessarily the stuff of romance and is not necessarily without its consequences. The singers (there are several) have the same thing on their minds as did the lonely man with the nasal voice, but here there is no hint of wine and roses. Although the [*478] majority below had difficulty discerning any criticism of the original in 2 Live Crew’s song, it assumed for purposes of its opinion that there was some.

We have less difficulty in finding that critical element in 2 Live Crew’s song than the Court of Appeals did, although having found it we will not take the further step of evaluating its quality. The threshold question when fair use is raised in defense of parody is whether a parodic character may reasonably be perceived. Whether, going beyond that, parody is in good taste or bad does not and should not matter to fair use. As Justice Holmes explained,

It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of [a work], outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one extreme some works of genius would be sure to miss appreciation. Their very novelty would make them repulsive until the public had learned the new language in which their author spoke.

Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239 (1903).

While we might not assign a high rank to the parodic element here, we think it fair to say that 2 Live Crew’s song reasonably could be perceived as commenting on the original or criticizing it, to some degree. 2 Live Crew juxtaposes the romantic musings of a man whose fantasy comes true, with degrading taunts, a bawdy demand for sex, and a sigh of relief from paternal responsibility. The later words can be taken as a comment on the naiveté of the original of an earlier day, as a rejection of its sentiment that ignores the ugliness of street life and the debasement that it signifies. It is this joinder of reference and ridicule that marks off the author’s choice of parody from the other types of comment and criticism that traditionally have had a claim to fair use protection as transformative works.

The Court of Appeals, however, immediately cut short the enquiry into 2 Live Crew’s fair use claim by confining its treatment of the first factor essentially to one relevant fact, the commercial nature of the use. In giving virtually dispositive weight to the commercial nature of the parody, the Court of Appeals erred.

The language of the statute makes clear that the commercial or nonprofit educational purpose of a work is only one element of the first factor enquiry into its purpose and character. Section 107(1) uses the term “including” to begin the dependent clause referring to commercial use, and the main clause speaks of a broader investigation into “purpose and character.” Accordingly, the mere fact that a use is educational and not for profit does not insulate it from a finding of infringement, any more the commercial character of a use bars a finding of fairness. If, indeed, commerciality carried presumptive force against a finding of fairness, the presumption would swallow nearly all of the illustrative uses listed in the preamble paragraph of § 107, including news reporting, comment, criticism, teaching, scholarship, and research, since these activities “are generally conducted for profit in this country.” Congress could not have intended such a rule, which certainly is not inferable from the common-law cases, arising as they did from the world of letters in which Samuel Johnson could pronounce that “[n]o man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.”

B

The second statutory factor, “the nature of the copyrighted work,” calls for recognition that some works are closer to the core of intended copyright protection than others, with the consequence that fair use is more difficult to establish when the former works are copied. See, e.g., Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S., at 237–238 [*479] (contrasting fictional short story with factual works); Harper & Row, 471 U.S., at 563–564 (contrasting soon-to-be-published memoir with published speech); Sony, 464 U.S., at 455, n. 40 (contrasting motion pictures with news broadcasts); Feist, 499 U.S., at 348–351 (contrasting creative works with bare factual compilations). We agree with both the District Court and the Court of Appeals that the Orbison original’s creative expression for public dissemination falls within the core of the copyright’s protective purposes. This fact, however, is not much help in this case, or ever likely to help much in separating the fair use sheep from the infringing goats in a parody case, since parodies almost invariably copy publicly known, expressive works.

C

The third factor asks whether “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole” are reasonable in relation to the purpose of the copying. Here, attention turns to the persuasiveness of a parodist’s justification for the particular copying done, and the enquiry will harken back to the first of the statutory factors, for, as in prior cases, we recognize that the extent of permissible copying varies with the purpose and character of the use. The facts bearing on this factor will also tend to address the fourth, by revealing the degree to which the parody may serve as a market substitute for the original or potentially licensed derivatives.

This factor calls for thought not only about the quantity of the materials used, but about their quality and importance, too. In Harper & Row, for example, the Nation had taken only some 300 words out of President Ford’s memoirs, but we signaled the significance of the quotations in finding them to amount to “the heart of the book,” the part most likely to be newsworthy and important in licensing serialization. We agree with the Court of Appeals that whether “a substantial portion of the infringing work was copied verbatim” from the copyrighted work is a relevant question, for it may reveal a dearth of transformative character or purpose under the first factor, or a greater likelihood of market harm under the fourth; a work composed primarily of an original, particularly its heart, with little added or changed, is more likely to be a merely superseding use, fulfilling demand for the original.

Where we part company with the court below is in applying these guides to parody, and in particular to parody in the song before us. Parody presents a difficult case. Parody’s humor, or in any event its comment, necessarily springs from recognizable allusion to its object through distorted imitation. Its art lies in the tension between a known original and its parodic twin. When parody takes aim at a particular original work, the parody must be able to conjure up at least enough of that original to make the object of its critical wit recognizable. What makes for this recognition is quotation of the original’s most distinctive or memorable features, which the parodist can be sure the audience will know. Once enough has been taken to assure identification, how much more is reasonable will depend, say, on the extent to which the song’s overriding purpose and character is to parody the original or, in contrast, the likelihood that the parody may serve as a market substitute for the original. But using some characteristic features cannot be avoided.

We think the Court of Appeals was insufficiently appreciative of parody’s need for the recognizable sight or sound when it ruled 2 Live Crew’s use unreasonable as a matter of law. It is true, of course, that 2 Live Crew copied the characteristic opening bass riff (or musical phrase) of the original, and true that the words of the first line copy the Orbison lyrics. But if quotation of the opening riff and the first line may be said to go to the “heart” of the original, the heart is also what most readily conjures up the song for parody, and it is the heart at which parody takes aim. Copying does not become excessive in relation to parodic purpose merely [*480] because the portion taken was the original’s heart. If 2 Live Crew had copied a significantly less memorable part of the original, it is difficult to see how its parodic character would have come through.

This is not, of course, to say that anyone who calls himself a parodist can skim the cream and get away scot free. In parody, as in news reporting, context is everything, and the question of fairness asks what else the parodist did besides go to the heart of the original. It is significant that 2 Live Crew not only copied the first line of the original, but thereafter departed markedly from the Orbison lyrics for its own ends. 2 Live Crew not only copied the bass riff and repeated it, but also produced otherwise distinctive sounds, interposing “scraper” noise, overlaying the music with solos in different keys, and altering the drum beat. This is not a case, then, where “a substantial portion” of the parody itself is composed of a “verbatim” copying of the original. It is not, that is, a case where the parody is so insubstantial, as compared to the copying, that the third factor must be resolved as a matter of law against the parodists.

Suffice it to say here that, as to the lyrics, we think the Court of Appeals correctly suggested that “no more was taken than necessary,” but just for that reason, we fail to see how the copying can be excessive in relation to its parodic purpose, even if the portion taken is the original’s “heart.” As to the music, we express no opinion whether repetition of the bass riff is excessive copying, and we remand to permit evaluation of the amount taken, in light of the song’s parodic purpose and character, its transformative elements, and considerations of the potential for market substitution sketched more fully below.

D

The fourth fair use factor is “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” It requires courts to consider not only the extent of market harm caused by the particular actions of the alleged infringer, but also whether unrestricted and widespread conduct of the sort engaged in by the defendant would result in a substantially adverse impact on the potential market for the original. [*552] The enquiry “must take account not only of harm to the original but also of harm to the market for derivative works.”

Since fair use is an affirmative defense, its proponent would have difficulty carrying the burden of demonstrating fair use without favorable evidence about relevant markets. In moving for summary judgment, 2 Live Crew left themselves at just such a disadvantage when they failed to address the effect on the market for rap derivatives, and confined themselves to uncontroverted submissions that there was no likely effect on the market for the original. They did not, however, thereby subject themselves to the evidentiary presumption applied by the Court of Appeals. In assessing the likelihood of significant market harm, the Court of Appeals quoted from language in Sony that “if the intended use is for commercial gain, that likelihood may be presumed. But if it is for a noncommercial purpose, the likelihood must be demonstrated.” The court reasoned that because the use of the copyrighted work is wholly commercial, we presume that a likelihood of future harm to Acuff–Rose exists.” In so doing, the court resolved the fourth factor against 2 Live Crew, just as it had the first, by applying a presumption about the effect of commercial use, a presumption which as applied here we hold to be error.

No “presumption” or inference of market harm that might find support in Sony is applicable to a case involving something beyond mere duplication for commercial purposes. Sony‘s discussion of a presumption contrasts a context of verbatim copying of the original in its entirety for commercial purposes, with [*481] the noncommercial context of Sony itself (home copying of television programming). In the former circumstances, what Sony said simply makes common sense: when a commercial use amounts to mere duplication of the entirety of an original. [*547] it clearly supersedes the objects of the original and serves as a market replacement for it, making it likely that cognizable market harm to the original will occur. But when, on the contrary, the second use is transformative, market substitution is at least less certain, and market harm may not be so readily inferred. Indeed, as to parody pure and simple, it is more likely that the new work will not affect the market for the original in a way cognizable under this factor, that is, by acting as a substitute for it.

We do not, of course, suggest that a parody may not harm the market at all, but when a lethal parody, like a scathing theater review, kills demand for the original, it does not produce a harm cognizable under the Copyright Act. Because parody may quite legitimately aim at garroting the original, destroying it commercially as well as artistically, the role of the courts is to distinguish between biting criticism that merely suppresses demand and copyright infringement, which usurps it.

This distinction between potentially remediable displacement and unremediable disparagement is reflected in the rule that there is no protectible derivative market for criticism. The market for potential derivative uses includes only those that creators of original works would in general develop or license others to develop. Yet the unlikelihood that creators of imaginative works will license critical reviews or lampoons of their own productions removes such uses from the very notion of a potential licensing market.

In explaining why the law recognizes no derivative market for critical works, including parody, we have, of course, been speaking of the later work as if it had nothing but a critical aspect. But the later work may have a more complex character, with effects not only in the arena of criticism but also in protectible markets for derivative works, too. In that sort of case, the law looks beyond the criticism to the other elements of the work, as it does here. 2 Live Crew’s song comprises not only parody but also rap music, and the derivative market for rap music is a proper focus of enquiry. Evidence of substantial harm to it would weigh against a finding of fair use, because the licensing of derivatives is an important economic incentive to the creation of originals.

Although 2 Live Crew submitted uncontroverted affidavits on the question of market harm to the original, neither they, nor Acuff–Rose, introduced evidence or affidavits addressing the likely effect of 2 Live Crew’s parodic rap song on the market for a nonparody, rap version of “Oh, Pretty Woman.” And while Acuff–Rose would have us find evidence of a rap market in the very facts that 2 Live Crew recorded a rap parody of “Oh, Pretty Woman” and another rap group sought a license to record a rap derivative, there was no evidence that a potential rap market was harmed in any way by 2 Live Crew’s parody, rap version. [It] is impossible to deal with the fourth factor except by recognizing that a silent record on an important factor bearing on fair use disentitled the proponent of the defense, 2 Live Crew, to summary judgment. The evidentiary hole will doubtless be plugged on remand.

III

It was error for the Court of Appeals to conclude that the commercial nature of 2 Live Crew’s parody of “Oh, [*482]Pretty Woman” rendered it presumptively unfair. No such evidentiary presumption is available to address either the first factor, the character and purpose of the use, or the fourth, market harm, in determining whether a transformative use, such as parody, is a fair one. The court also erred in holding that 2 Live Crew had necessarily copied excessively from the Orbison original, considering the parodic purpose of the use. We therefore reverse the judgment of the Court of Appeals and remand the case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Campbell

Question 1. According to Campbell, what is the significance of a court’s determination that the purpose and character of an otherwise infringing use is “transformative”?

Question 2. Which of the following is always treated as fair use?

Some things to consider when reading Sony:

- The portion of this decision addressing the question of indirect infringement appeared earlier in this book.

- The excerpt of Sony presented here focuses on whether consumers’ use of the VTR to record copyrighted television broadcasts is fair use. The Court finds that much of this recording is for the purpose of “time-shifting,” i.e., so that the consumer can watch the television broadcast at a later time. Take particular note of how the Court applies the four fair use factors, and the policy concerns expressed by the Court.

- Note the Court’s emphasis on “the commercial and nonprofit character of an activity” in analyzing the first and fourth factors, and its statement that at least some “commercial or profit-making” uses are presumptively unfair. Recall that in Campbell the Court pulled back from that position, holding that “[n]o such evidentiary presumption is available to address either the first factor, the character and [*483] purpose of the use, or the fourth, market harm, in determining whether a transformative use, such as parody, is a fair one.”

- Ask yourself what the difference is between a transformative use (like the parody at issue in Campbell) and a productive use (as discussed by the Sony dissent).

- What do you think about the majority’s conclusion that the evidence of record did not establish a meaningful likelihood of future harm, and the dissent’s critique of that conclusion?

Sony Corp. v. Universal City Studios, Inc.

464 U.S. 417 (1984)

Justice STEVENS delivered the opinion of the Court.

[Editor’s note: Facts and indirect infringement aspects of this decision appear earlier in this casebook. The following excerpt addresses the question of whether unauthorized time-shifting is fair use. The Court of Appeals concluded as a matter of law that the home use of a VTR was not a fair use because it was not a “productive use.”]

IV

B. Unauthorized Time-Shifting

Even unauthorized uses of a copyrighted work are not necessarily infringing. An unlicensed use of the copyright is not an infringement unless it conflicts with one of the specific exclusive rights conferred by the copyright statute. Moreover, the definition of exclusive rights in § 106 of the present Act is prefaced by the words “subject to sections 107 through 118.” Those sections describe a variety of uses of copyrighted material that “are not infringements of copyright notwithstanding the provisions of § 106.” The most pertinent in this case is § 107, the legislative endorsement of the doctrine of “fair use.”

That section identifies various factors that enable a Court to apply an “equitable rule of reason” analysis to particular claims of infringement. Although not conclusive, the first factor requires that “the commercial or nonprofit character of an activity” be weighed in any fair use decision. If the Betamax were used to make copies for a commercial or profit-making purpose, such use would presumptively be unfair. The contrary presumption is appropriate here, however, because the District Court’s findings plainly establish that time-shifting for private home use must be characterized as a noncommercial, nonprofit activity. Moreover, when one considers the nature of a televised copyrighted audiovisual work, and that timeshifting merely enables a viewer to see such a work which he had been invited to witness in its entirety free of charge, the fact that the entire work is reproduced does not have its ordinary effect of militating against a finding of fair use.

This is not, however, the end of the inquiry because Congress has also directed us to consider “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” The purpose of copyright is to create incentives for creative effort. Even copying for noncommercial purposes may impair the copyright holder’s ability to obtain the rewards that Congress intended him to have. But a use that has no demonstrable effect upon the potential market for, or the value of, the copyrighted work need not be [*484] prohibited in order to protect the author’s incentive to create. The prohibition of such noncommercial uses would merely inhibit access to ideas without any countervailing benefit.

Thus, although every commercial use of copyrighted material is presumptively an unfair exploitation of the monopoly privilege that belongs to the owner of the copyright, noncommercial uses are a different matter. A challenge to a noncommercial use of a copyrighted work requires proof either that the particular use is harmful, or that if it should become widespread, it would adversely affect the potential market for the copyrighted work. Actual present harm need not be shown; such a requirement would leave the copyright holder with no defense against predictable damage. Nor is it necessary to show with certainty that future harm will result. What is necessary is a showing by a preponderance of the evidence that some meaningful likelihood of future harm exists. If the intended use is for commercial gain, that likelihood may be presumed. But if it is for a noncommercial purpose, the likelihood must be demonstrated.

In this case, respondents failed to carry their burden with regard to home time-shifting. The District Court described respondents’ evidence as follows:

Plaintiffs’ experts admitted at several points in the trial that the time-shifting without librarying would result in “not a great deal of harm.” Plaintiffs’ greatest concern about time-shifting is with “a point of important philosophy that transcends even commercial judgment.” They fear that with any Betamax usage, “invisible boundaries” are passed: “the copyright owner has lost control over his program.”

Later in its opinion, the District Court observed:

Most of plaintiffs’ predictions of harm hinge on speculation about audience viewing patterns and ratings, a measurement system which Sidney Sheinberg, MCA’s president, calls a “black art” because of the significant level of imprecision involved in the calculations.

There was no need for the District Court to say much about past harm. “Plaintiffs have admitted that no actual harm to their copyrights has occurred to date.”

On the question of potential future harm from time-shifting, the District Court offered a more detailed analysis of the evidence. It rejected respondents’ “fear that persons ‘watching’ the original telecast of a program will not be measured in the live audience and the ratings and revenues will decrease,” by observing that current measurement technology allows the Betamax audience to be reflected. It rejected respondents’ prediction “that live television or movie audiences will decrease as more people watch Betamax tapes as an alternative,” with the observation that “[t]here is no factual basis for [the underlying] assumption.” It rejected respondents’ “fear that time-shifting will reduce audiences for telecast reruns,” and concluded instead that “given current market practices, this should aid plaintiffs rather than harm them.” And it declared that respondents’ suggestion “that theater or film rental exhibition of a program will suffer because of time-shift recording of that program” “lacks merit.”

After completing that review, the District Court restated its overall conclusion several times, in several different ways. “Harm from time-shifting is speculative and, at best, minimal.” “The audience benefits from the time-shifting capability have already been discussed. It is not implausible that benefits could also accrue to plaintiffs, broadcasters, and advertisers, as the Betamax makes it possible for more persons to view [*485] their broadcasts.” “No likelihood of harm was shown at trial, and plaintiffs admitted that there had been no actual harm to date.” “Testimony at trial suggested that Betamax may require adjustments in marketing strategy, but it did not establish even a likelihood of harm.” “Television production by plaintiffs today is more profitable than it has ever been, and, in five weeks of trial, there was no concrete evidence to suggest that the Betamax will change the studios’ financial picture.”

The District Court’s conclusions are buttressed by the fact that to the extent time-shifting expands public access to freely broadcast television programs, it yields societal benefits. Earlier this year, in Community Television of Southern California v. Gottfried, S.Ct. 885, 891–892 (1983), we acknowledged the public interest in making television broadcasting more available. Concededly, that interest is not unlimited. But it supports an interpretation of the concept of “fair use” that requires the copyright holder to demonstrate some likelihood of harm before he may condemn a private act of time-shifting as a violation of federal law.

When these factors are all weighed in the “equitable rule of reason” balance, we must conclude that this record amply supports the District Court’s conclusion that home time-shifting is fair use.

Justice BLACKMUN, with whom Justice MARSHALL, Justice POWELL, and Justice REHNQUIST join, dissenting.

Copyright is based on the belief that by granting authors the exclusive rights to reproduce their works, they are given an incentive to create, and that encouragement of individual effort by personal gain is the best way to advance public welfare through the talents of authors and inventors in “Science and the useful Arts.” The monopoly created by copyright thus rewards the individual author in order to benefit the public.

There are situations, nevertheless, in which strict enforcement of this monopoly would inhibit the very “Progress of Science and useful Arts” that copyright is intended to promote. An obvious example is the researcher or scholar whose own work depends on the ability to refer to and to quote the work of prior scholars. Obviously, no author could create a new work if he were first required to repeat the research of every author who had gone before him. The scholar, like the ordinary user, of course could be left to bargain with each copyright owner for permission to quote from or refer to prior works. But there is a crucial difference between the scholar and the ordinary user. When the ordinary user decides that the owner’s price is too high, and forgoes use of the work, only the individual is the loser. When the scholar forgoes the use of a prior work, not only does his own work suffer, but the public is deprived of his contribution to knowledge. The scholar’s work, in other words, produces external benefits from which everyone profits. In such a case, the fair use doctrine acts as a form of subsidy—albeit at the first author’s expense—to permit the second author to make limited use of the first author’s work for the public good.

A similar subsidy may be appropriate in a range of areas other than pure scholarship. The situations in which fair use is most commonly recognized are listed in § 107 itself; fair use may be found when a work is used “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, … scholarship, or research.” Each of these uses, however, reflects a common theme: each is a productive use, resulting in some added benefit to the public beyond that produced by the first author’s work. The fair use doctrine, in other words, permits works to be used for “socially laudable purposes.” I am aware of no case in which the reproduction of a copyrighted work for the sole benefit of the user has been held to be fair use.

I do not suggest, of course, that every productive use is a fair use. A finding of fair use still must depend on [*486] the facts of the individual case, and on whether, under the circumstances, it is reasonable to expect the user to bargain with the copyright owner for use of the work. The fair use doctrine must strike a balance between the dual risks created by the copyright system: on the one hand, that depriving authors of their monopoly will reduce their incentive to create, and, on the other, that granting authors a complete monopoly will reduce the creative ability of others. But when a user reproduces an entire work and uses it for its original purpose, with no added benefit to the public, the doctrine of fair use usually does not apply. There is then no need whatsoever to provide the ordinary user with a fair use subsidy at the author’s expense.

The making of a videotape recording for home viewing is an ordinary rather than a productive use of the Studios’ copyrighted works. Copyright gives the author a right to limit or even to cut off access to his work. A VTR recording creates no public benefit sufficient to justify limiting this right.

It may be tempting, as, in my view, the Court today is tempted, to stretch the doctrine of fair use so as to permit unfettered use of this new technology in order to increase access to television programming. But such an extension risks eroding the very basis of copyright law, by depriving authors of control over their works and consequently of their incentive to create.

…

I recognize, nevertheless, that there are situations where permitting even an unproductive use would have no effect on the author’s incentive to create, that is, where the use would not affect the value of, or the market for, the author’s work. Photocopying an old newspaper clipping to send to a friend may be an example; pinning a quotation on one’s bulletin board may be another. In each of these cases, the effect on the author is truly de minimis. Thus, even though these uses provide no benefit to the public at large, no purpose is served by preserving the author’s monopoly, and the use may be regarded as fair.

The Studios have identified a number of ways in which VTR recording could damage their copyrights. VTR recording could reduce their ability to market their works in movie theaters and through the rental or sale of pre-recorded videotapes or videodiscs; it also could reduce their rerun audience, and consequently the license fees available to them for repeated showings. Moreover, advertisers may be willing to pay for only “live” viewing audiences, if they believe VTR viewers will delete commercials or if rating services are unable to measure VTR use; if this is the case, VTR recording could reduce the license fees the Studios are able to charge even for first-run showings. Library-building may raise the potential for each of the types of harm identified by the Studios, and time-shifting may raise the potential for substantial harm as well.

…

The Court confidently describes time-shifting as a noncommercial, nonprofit activity. It is clear, however, that personal use of programs that have been copied without permission is not what § 107(1) protects. The intent of the section is to encourage users to engage in activities the primary benefit of which accrues to others. Time-shifting involves no such humanitarian impulse. It is likewise something of a mischaracterization of time-shifting to describe it as noncommercial in the sense that that term is used in the statute. As one commentator has observed, time-shifting is noncommercial in the same sense that stealing jewelry and wearing it—instead of reselling it—is noncommercial. Purely consumptive uses are certainly not what the fair use doctrine was designed to protect, and the awkwardness of applying the [*487] statutory language to time-shifting only makes clearer that fair use was designed to protect only uses that are productive.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Sony

Question 1. What factors led the Sony Court to conclude that the record supported the district court’s conclusion that home time-shifting is fair use?

Some things to consider when reading Author’s Guild:

- In this case, Google has been sued by the owners of copyrights in books, based on the unauthorized copying of books that occurred in connection with Google’s Library Project and its Google Books project. The decision provides a good description of these projects, and the massive amount of unauthorized copying that occurred. There is no doubt that Google’s actions constitute copyright infringement in the absence of a fair use defense.

- Make note of all the steps Google took to try to ensure that its actions constitute fair use.

- Understand the court’s fair use analysis, which is largely based on Campbell. Pay particular attention to the court’s focus on the purpose behind Google’s copying of the books and its use of the copies, such as the indexing and the display of “snippets.”

- As noted by the court, in this case Google “test[ed] the boundaries of fair use.”

- This decision could be particularly relevant to the question of whether the massive copying that has occurred for the purposes of training generative artificial intelligence (AI) models can be defended as fair use, a topic that is addressed in the generative AI section of this casebook.

- On what basis does the court conclude that Google’s purpose was transformative?

- How were the facts different in this case than in the earlier HathiTrust decision?

- Note the court’s distinction between a “transformative” fair use of the plaintiff’s work and an infringing derivative work that “transformed” the original. These two different legal meanings of “transform” will be relevant in the Andy Warhol decision that appears later in this section.

[*488] Authors Guild v. Google, Inc.

804 F.3d 202 (2d Cir. 2015)

LEVAL, Circuit Judge:

This copyright dispute tests the boundaries of fair use. Plaintiffs, who are authors of published books under copyright, sued Google, Inc. (“Google”) for copyright infringement in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. They appeal from the grant of summary judgment in Google’s favor. Through its Library Project and its Google Books project, acting without permission of rights holders, Google has made digital copies of tens of millions of books, including Plaintiffs’, that were submitted to it for that purpose by major libraries. Google has scanned the digital copies and established a publicly available search function. An Internet user can use this function to search without charge to determine whether the book contains a specified word or term and also see “snippets” of text containing the searched-for terms. In addition, Google has allowed the participating libraries to download and retain digital copies of the books they submit, under agreements which commit the libraries not to use their digital copies in violation of the copyright laws. These activities of Google are alleged to constitute infringement of Plaintiffs’ copyrights. Plaintiffs sought injunctive and declaratory relief as well as damages.

Google defended on the ground that its actions constitute “fair use,” which, under 17 U.S.C. § 107, is “not an infringement.” The district court agreed. Plaintiffs brought this appeal.

Plaintiffs contend the district court’s ruling was flawed in several respects. They argue: (1) Google’s digital copying of entire books, allowing users through the snippet function to read portions, is not a “transformative use” within the meaning of Campbell v. Acuff–Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994), and provides a substitute for Plaintiffs’ works; (2) notwithstanding that Google provides public access to the search and snippet functions without charge and without advertising, its ultimate commercial profit motivation and its derivation of revenue from its dominance of the world-wide Internet search market to which the books project contributes, preclude a finding of fair use; (3) even if Google’s copying and revelations of text do not infringe plaintiffs’ books, they infringe Plaintiffs’ derivative rights in search functions, depriving Plaintiffs of revenues or other benefits they would gain from licensed search markets; (4) Google’s storage of digital copies exposes Plaintiffs to the risk that hackers will make their books freely (or cheaply) available on the Internet, destroying the value of their copyrights; and (5) Google’s distribution of digital copies to participant libraries is not a transformative use, and it subjects Plaintiffs to the risk of loss of copyright revenues through access allowed by libraries. We reject these arguments and conclude that the district court correctly sustained Google’s fair use defense.

Google’s making of a digital copy to provide a search function is a transformative use, which augments public knowledge by making available information about Plaintiffs’ books without providing the public with a substantial substitute for matter protected by the Plaintiffs’ copyright interests in the original works or derivatives of them. The same is true, at least under present conditions, of Google’s provision of the snippet function. Plaintiffs’ contention that Google has usurped their opportunity to access paid and unpaid licensing markets for substantially the same functions that Google provides fails, in part because the licensing markets in fact involve very different functions than those that Google provides, and in part [*489] because an author’s derivative rights do not include an exclusive right to supply information (of the sort provided by Google) about her works. Google’s profit motivation does not in these circumstances justify denial of fair use. Google’s program does not, at this time and on the record before us, expose Plaintiffs to an unreasonable risk of loss of copyright value through incursions of hackers. Finally, Google’s provision of digital copies to participating libraries, authorizing them to make non-infringing uses, is non-infringing, and the mere speculative possibility that the libraries might allow use of their copies in an infringing manner does not make Google a contributory infringer. Plaintiffs have failed to show a material issue of fact in dispute.

We affirm the judgment.

BACKGROUND

I. Plaintiffs

The author-plaintiffs are Jim Bouton, author of Ball Four; Betty Miles, author of The Trouble with Thirteen; and Joseph Goulden, author of The Superlawyers: The Small and Powerful World of the Great Washington Law Firms. Each of them has a legal or beneficial ownership in the copyright for his or her book. Their books have been scanned without their permission by Google, which made them available to Internet users for search and snippet view on Google’s website.

II. Google Books and the Google Library Project

Google’s Library Project, which began in 2004, involves bilateral agreements between Google and a number of the world’s major research libraries. Under these agreements, the participating libraries select books from their collections to submit to Google for inclusion in the project. Google makes a digital scan of each book, extracts a machine-readable text, and creates an index of the machine-readable text of each book. Google retains the original scanned image of each book, in part so as to improve the accuracy of the machine-readable texts and indices as image-to-text conversion technologies improve.

Since 2004, Google has scanned, rendered machine-readable, and indexed more than 20 million books, including both copyrighted works and works in the public domain. The vast majority of the books are non-fiction, and most are out of print. All of the digital information created by Google in the process is stored on servers protected by the same security systems Google uses to shield its own confidential information.

The digital corpus created by the scanning of these millions of books enables the Google Books search engine. Members of the public who access the Google Books website can enter search words or terms of their own choice, receiving in response a list of all books in the database in which those terms appear, as well as the number of times the term appears in each book. A brief description of each book, entitled “About the Book,” gives some rudimentary additional information, including a list of the words and terms that appear with most frequency in the book. It sometimes provides links to buy the book online and identifies libraries where the book can be found.[4] The search tool permits a researcher to identify those books, out of millions, that do, as well as those that do not, use the terms selected by the researcher. Google notes that this identifying information instantaneously supplied would otherwise not be obtainable in lifetimes of searching. [*490]

No advertising is displayed to a user of the search function. Nor does Google receive payment by reason of the searcher’s use of Google’s link to purchase the book.

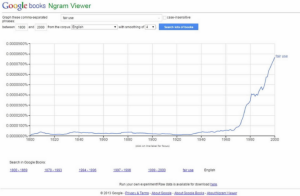

The search engine also makes possible new forms of research, known as “text mining” and “data mining.” Google’s “ngrams” research tool draws on the Google Library Project corpus to furnish statistical information to Internet users about the frequency of word and phrase usage over centuries.[5] This tool permits users to discern fluctuations of interest in a particular subject over time and space by showing increases and decreases in the frequency of reference and usage in different periods and different linguistic regions. It also allows researchers to comb over the tens of millions of books Google has scanned in order to examine “word frequencies, syntactic patterns, and thematic markers” and to derive information on how nomenclature, linguistic usage, and literary style have changed over time.

The Google Books search function also allows the user a limited viewing of text. In addition to telling the number of times the word or term selected by the searcher appears in the book, the search function will display a maximum of three “snippets” containing it. A snippet is a horizontal segment comprising ordinarily an eighth of a page. Each page of a conventionally formatted book in the Google Books database is divided into eight non-overlapping horizontal segments, each such horizontal segment being a snippet. (Thus, for such a book with 24 lines to a page, each snippet is comprised of three lines of text.) Each search for a particular word or term within a book will reveal the same three snippets, regardless of the number of computers from which the search is launched. Only the first usage of the term on a given page is displayed. Thus, if the top snippet of a page contains two (or more) words for which the user searches, and Google’s program is fixed to reveal that particular snippet in response to a search for either term, the second search will duplicate the snippet already revealed by the first search, rather than moving to reveal a different snippet containing the word because the first snippet was already revealed. Google’s program does not allow a searcher to increase the number of snippets revealed by repeated entry of the same search term or by entering searches from different computers. A searcher can view more than three snippets of a book by entering additional searches for different terms. However, Google makes permanently unavailable for snippet view one snippet on each page and one complete page out of every ten—a process Google calls “blacklisting.”

Google also disables snippet view entirely for types of books for which a single snippet is likely to satisfy the searcher’s present need for the book, such as dictionaries, cookbooks, and books of short poems. Finally, since 2005, Google will exclude any book altogether from snippet view at the request of the rights holder by the submission of an online form.

Under its contracts with the participating libraries, Google allows each library to download copies—of both the digital image and machine-readable versions—of the books that library submitted to Google for scanning (but not of books submitted by other libraries). This is done by giving each participating library access to the Google Return Interface (“GRIN”). The agreements between Google and the libraries, although not in all respects uniform, require the libraries to abide by copyright law in utilizing the digital copies they download and to take precautions to prevent dissemination of their digital copies to the public at large.

DISCUSSION

I. The Law of Fair Use

[*491] The ultimate goal of copyright is to expand public knowledge and understanding, which copyright seeks to achieve by giving potential creators exclusive control over copying of their works, thus giving them a financial incentive to create informative, intellectually enriching works for public consumption. This objective is clearly reflected in the Constitution’s empowerment of Congress “To promote the Progress of Science … by securing for limited Times to Authors … the exclusive Right to their respective Writings.” U.S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 8 (emphasis added). Thus, while authors are undoubtedly important intended beneficiaries of copyright, the ultimate, primary intended beneficiary is the public, whose access to knowledge copyright seeks to advance by providing rewards for authorship.

For nearly three hundred years, since shortly after the birth of copyright in England in 1710, courts have recognized that, in certain circumstances, giving authors absolute control over all copying from their works would tend in some circumstances to limit, rather than expand, public knowledge. Courts thus developed the doctrine, eventually named fair use, which permits unauthorized copying in some circumstances, so as to further copyright’s very purpose, to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts. Although well established in the common law development of copyright, fair use was not recognized in the terms of our statute until the adoption of § 107 in the Copyright Act of 1976.

Section 107, in its present form, provides:

[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work … for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

17 U.S.C. § 107. As the Supreme Court has designated fair use an affirmative defense, see Campbell, 510 U.S. at 590, the party asserting fair use bears the burden of proof.

The statute calls for case-by-case analysis and is not to be simplified with bright-line rules. Section 107’s four factors are not to be treated in isolation, one from another. All are to be explored, and the results weighed together, in light of the purposes of copyright. Each factor thus stands as part of a multifaceted assessment of the crucial question: how to define the boundary limit of the original author’s exclusive rights in order to best serve the overall objectives of the copyright law to expand public learning while protecting the incentives of authors to create for the public good. [*492]

At the same time, the Supreme Court has made clear that some of the statute’s four listed factors are more significant than others. The Court observed in Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises that the fourth factor, which assesses the harm the secondary use can cause to the market for, or the value of, the copyright for the original, “is undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use.” 471 U.S. 539, 566 (1985). This is consistent with the fact that the copyright is a commercial right, intended to protect the ability of authors to profit from the exclusive right to merchandise their own work.

In Campbell, the Court stressed also the importance of the first factor, the “purpose and character of the secondary use.” The more the appropriator is using the copied material for new, transformative purposes, the more it serves copyright’s goal of enriching public knowledge and the less likely it is that the appropriation will serve as a substitute for the original or its plausible derivatives, shrinking the protected market opportunities of the copyrighted work.

With this background, we proceed to discuss each of the statutory factors, as illuminated by Campbell and subsequent case law, in relation to the issues here in dispute.

II. The Search and Snippet View Functions

A. Factor One

(1) Transformative purpose. Campbell ‘s explanation of the first factor’s inquiry into the “purpose and character” of the secondary use focuses on whether the new work merely supersedes the objects’ of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose. It asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is “transformative.” While recognizing that a transformative use is not absolutely necessary for a finding of fair use, the opinion further explains that the goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works and that such works thus lie at the heart of the fair use doctrine’s guarantee of breathing space within the confines of copyright. In other words, transformative uses tend to favor a fair use finding because a transformative use is one that communicates something new and different from the original or expands its utility, thus serving copyright’s overall objective of contributing to public knowledge.

The word “transformative” cannot be taken too literally as a sufficient key to understanding the elements of fair use. It is rather a suggestive symbol for a complex thought, and does not mean that any and all changes made to an author’s original text will necessarily support a finding of fair use. The Supreme Court’s discussion in Campbell gave important guidance on assessing when a transformative use tends to support a conclusion of fair use. The defendant in that case defended on the ground that its work was a parody of the original and that parody is a time-honored category of fair use. Explaining why parody makes a stronger, or in any event more obvious, claim of fair use than satire, the Court stated,

The heart of any parodist’s claim to quote from existing material is the use of a prior author’s composition to comment on that author’s works. If, on the contrary, the commentary has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, which the alleged infringer merely uses to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh, the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish). Parody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s [*493] imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing. (emphasis added).

In other words, the would-be fair user of another’s work must have justification for the taking. A secondary author is not necessarily at liberty to make wholesale takings of the original author’s expression merely because of how well the original author’s expression would convey the secondary author’s different message. Among the best recognized justifications for copying from another’s work is to provide comment on it or criticism of it. A taking from another author’s work for the purpose of making points that have no bearing on the original may well be fair use, but the taker would need to show a justification. This part of the Supreme Court’s discussion is significant in assessing Google’s claim of fair use because, as discussed extensively below, Google’s claim of transformative purpose for copying from the works of others is to provide otherwise unavailable information about the originals.

A further complication that can result from oversimplified reliance on whether the copying involves transformation is that the word “transform” also plays a role in defining “derivative works,” over which the original rights holder retains exclusive control. Section 106 of the Act specifies the “exclusive right[ ]” of the copyright owner “(2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work.” The statute defines derivative works largely by example, rather than explanation. The examples include “translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgement, condensation,” to which list the statute adds “any other form in which a work may be … transformed.” 17 U.S.C. § 101 (emphasis added). While such changes can be described as transformations, they do not involve the kind of transformative purpose that favors a fair use finding. The statutory definition suggests that derivative works generally involve transformations in the nature of changes of form. By contrast, copying from an original for the purpose of criticism or commentary on the original or provision of information about it, tends most clearly to satisfy Campbell ‘s notion of the “transformative” purpose involved in the analysis of Factor One.

With these considerations in mind, we first consider whether Google’s search and snippet views functions satisfy the first fair use factor with respect to Plaintiffs’ rights in their books. (The question whether these functions might infringe upon Plaintiffs’ derivative rights is discussed in the next Part.)

(2) Search Function. We have no difficulty concluding that Google’s making of a digital copy of Plaintiffs’ books for the purpose of enabling a search for identification of books containing a term of interest to the searcher involves a highly transformative purpose, in the sense intended by Campbell. Our court’s exemplary discussion in Authors Guild, Inc. v. HathiTrust, 755 F.3d 87 (2d Cir. 2014) informs our ruling. That case involved a dispute that is closely related, although not identical, to this one. Authors brought claims of copyright infringement against HathiTrust, an entity formed by libraries participating in the Google Library Project to pool the digital copies of their books created for them by Google. The suit challenged various usages HathiTrust made of the digital copies. Among the challenged uses was HathiTrust’s offer to its patrons of “full-text searches,” which, very much like the search offered by Google Books to Internet users, permitted patrons of the libraries to locate in which of the digitized books specific words or phrases appeared. (HathiTrust’s search facility did not include the snippet view function, or any other display of text.) We concluded that both the making of the digital copies and the use of those copies to offer the search tool were fair uses. [*494]

Notwithstanding that the libraries had downloaded and stored complete digital copies of entire books, we noted that such copying was essential to permit searchers to identify and locate the books in which words or phrases of interest to them appeared. We concluded that the creation of a full-text searchable database is a quintessentially transformative use as the result of a word search is different in purpose, character, expression, meaning, and message from the page (and the book) from which it is drawn.

As with HathiTrust, the purpose of Google’s copying of the original copyrighted books is to make available significant information about those books, permitting a searcher to identify those that contain a word or term of interest, as well as those that do not include reference to it. In addition, through the ngrams tool, Google allows readers to learn the frequency of usage of selected words in the aggregate corpus of published books in different historical periods. We have no doubt that the purpose of this copying is the sort of transformative purpose described in Campbell as strongly favoring satisfaction of the first factor.

(3) Snippet View. Plaintiffs correctly point out that this case is significantly different from HathiTrust in that the Google Books search function allows searchers to read snippets from the book searched, whereas HathiTrust did not allow searchers to view any part of the book. Snippet view adds important value to the basic transformative search function, which tells only whether and how often the searched term appears in the book. Merely knowing that a term of interest appears in a book does not necessarily tell the searcher whether she needs to obtain the book, because it does not reveal whether the term is discussed in a manner or context falling within the scope of the searcher’s interest. For example, a searcher seeking books that explore Einstein’s theories, who finds that a particular book includes 39 usages of “Einstein,” will nonetheless conclude she can skip that book if the snippets reveal that the book speaks of “Einstein” because that is the name of the author’s cat. In contrast, the snippet will tell the searcher that this is a book she needs to obtain if the snippet shows that the author is engaging with Einstein’s theories.

Google’s division of the page into tiny snippets is designed to show the searcher just enough context surrounding the searched term to help her evaluate whether the book falls within the scope of her interest (without revealing so much as to threaten the author’s copyright interests). Snippet view thus adds importantly to the highly transformative purpose of identifying books of interest to the searcher. With respect to the first factor test, it favors a finding of fair use (unless the value of its transformative purpose is overcome by its providing text in a manner that offers a competing substitute for Plaintiffs’ books, which we discuss under factors three and four below).

(4) Google’s Commercial Motivation. Plaintiffs also contend that Google’s commercial motivation weighs in their favor under the first factor. Google’s commercial motivation distinguishes this case from HathiTrust, as the defendant in that case was a non-profit entity founded by, and acting as the representative of, libraries. Although Google has no revenues flowing directly from its operation of the Google Books functions, Plaintiffs stress that Google is profit-motivated and seeks to use its dominance of book search to fortify its overall dominance of the Internet search market, and that thereby Google indirectly reaps profits from the Google Books functions.

In explaining the first fair use factor, the Court [in Campbell] clarified that the more transformative the secondary work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use. Our court has since repeatedly rejected the contention that commercial motivation [*495] should outweigh a convincing transformative purpose and absence of significant substitutive competition with the original.

While we recognize that in some circumstances, a commercial motivation on the part of the secondary user will weigh against her, especially when a persuasive transformative purpose is lacking, we see no reason in this case why Google’s overall profit motivation should prevail as a reason for denying fair use over its highly convincing transformative purpose, together with the absence of significant substitutive competition, as reasons for granting fair use. Many of the most universally accepted forms of fair use, such as news reporting and commentary, quotation in historical or analytic books, reviews of books, and performances, as well as parody, are all normally done commercially for profit.

B. Factor Two

The second fair use factor directs consideration of the “nature of the copyrighted work.” While the “transformative purpose” inquiry discussed above is conventionally treated as a part of first factor analysis, it inevitably involves the second factor as well. One cannot assess whether the copying work has an objective that differs from the original without considering both works, and their respective objectives.

The second factor has rarely played a significant role in the determination of a fair use dispute. See WILLIAM F. PATRY, PATRY ON FAIR USE § 4.1 (2015). The Supreme Court in Harper & Row made a passing observation in dictum that, “the law generally recognizes a greater need to disseminate factual works than works of fiction or fantasy.” 471 U.S. 539, 563 (1985). Courts have sometimes speculated that this might mean that a finding of fair use is more favored when the copying is of factual works than when copying is from works of fiction. However, while the copyright does not protect facts or ideas set forth in a work, it does protect that author’s manner of expressing those facts and ideas. At least unless a persuasive fair use justification is involved, authors of factual works, like authors of fiction, should be entitled to copyright protection of their protected expression. The mere fact that the original is a factual work therefore should not imply that others may freely copy it. Those who report the news undoubtedly create factual works. It cannot seriously be argued that, for that reason, others may freely copy and re-disseminate news reports.