Chapter 14: Generative Artificial Intelligence

[*600] One of the most widely used generative artificial intelligence (AI) products is ChatGPT.[1] When prompted with the query of “what is artificial intelligence,” ChatGPT responded:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a branch of computer science focused on creating systems and machines capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. These tasks include understanding language, recognizing patterns, solving problems, learning from experience, and making decisions.

This response comports with this author’s understanding of the term. When prompted with the query of “what is generative AI,” ChatGPT provided the following response, which again comports with this author’s understanding:

Generative AI refers to a type of artificial intelligence that can generate new content, such as text, images, audio, video, and other data, based on patterns it has learned from existing data. It leverages advanced machine learning techniques, particularly neural networks, to understand and mimic the style, structure, and context of the input data.

Rapid and widely publicized advances in generative AI are raising a host of legal questions, including in the area of copyright law. Two of the fundamental questions are (1) to what extent are works that have been generated by AI, either entirely or with some substantial human involvement, eligible for copyright protection; and (2) to what extent are the creators and users of AI models liable for copyright infringement (either directly or secondarily), particularly when the AI model has been trained with copyrighted materials without the authorization of the copyright owners, for example by “scraping” the web. We are still in the very early days of trying to sort out the copyright issues raised by AI, but we are starting to see some decisions. This section of the casebook presents four such decisions, the first two having to do with questions of copyrightability, and the second two with infringement, including some analysis of the fair use defense.

———

Some things to consider when reading Thaler:

- In this case, a federal court affirms a decision by the Copyright Office not to register a work that the applicant for registration characterized as being “generated entirely by an artificial system absent human involvement” based on its holding that “human authorship is an essential part of a valid copyright claim.”

- Note the court’s use of precedent, including Supreme Court decisions that appeared earlier in this casebook, i.e., Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony and Mazer v. Stein, to arrive at its conclusion that only a human can be an author. The court also invokes textual and policy-based arguments in reaching its conclusion that human authorship is required for copyright.

- The plaintiff attempted to change its argument during the course of the appeal, first maintaining that the work was entirely AI-generated, and then flip-flopping and attempting to argue that he played a [*601] controlling role in generating the work. The court properly declined to entertain these new arguments that were inconsistent with the plaintiff’s representations before the Copyright Office Review Board.

- Consider the policy implications if every output of a “Creativity Machine” was granted a copyright.

Thaler v. Perlmutter

687 F. Supp. 3d 140 (D.D.C. 2023)

BERYL A. HOWELL, United States District Judge

Plaintiff Stephen Thaler owns a computer system he calls the “Creativity Machine,” which he claims generated a piece of visual art of its own accord. He sought to register the work for a copyright, listing the computer system as the author and explaining that the copyright should transfer to him as the owner of the machine. The Copyright Office denied the application on the grounds that the work lacked human authorship, a prerequisite for a valid copyright to issue, in the view of the Register of Copyrights. Plaintiff challenged that denial, culminating in this lawsuit against the United States Copyright Office and Shira Perlmutter, in her official capacity as the Register of Copyrights and the Director of the United States Copyright Office (“defendants”). Both parties have now moved for summary judgment, which motions present the sole issue of whether a work generated entirely by an artificial system absent human involvement should be eligible for copyright. For the reasons explained below, defendants are correct that human authorship is an essential part of a valid copyright claim, and therefore plaintiff’s pending motion for summary judgment is denied and defendants’ pending cross-motion for summary judgment is granted.

I. BACKGROUND

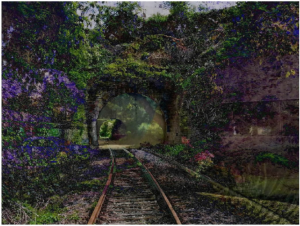

Plaintiff develops and owns computer programs he describes as having “artificial intelligence” (“AI”) capable of generating original pieces of visual art, akin to the output of a human artist. One such AI system—the so-called “Creativity Machine”—produced the work at issue here, titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise:”

[*602]

After its creation, plaintiff attempted to register this work with the Copyright Office. In his application, he identified the author as the Creativity Machine, and explained the work had been “autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine,” but that plaintiff sought to claim the copyright of the “computer-generated work” himself “as a work-for-hire to the owner of the Creativity Machine.” The Copyright Office denied the application on the basis that the work “lack[ed] the human authorship necessary to support a copyright claim,” noting that copyright law only extends to works created by human beings.

Plaintiff requested reconsideration of his application, confirming that the work “was autonomously generated by an AI” and “lack[ed] traditional human authorship,” but contesting the Copyright Office’s human authorship requirement and urging that AI should be “acknowledge[d] … as an author where it otherwise meets authorship criteria, with any copyright ownership vesting in the AI’s owner.” Again, the Copyright Office refused to register the work, reiterating its original rationale that “[b]ecause copyright law is limited to ‘original intellectual conceptions of the author,’ the Office will refuse to register a claim if it determines that a human being did not create the work.” Copyright Office Refusal Letter Dated March 30, 2020 (“Second Refusal Letter”) at 1, ECF No. 13-6 (quoting Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884) and citing 17 U.S.C. § 102(a); U.S. Copyright Office, Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices § 306 (3d ed. 2017)). Plaintiff made a second request for reconsideration along the same lines as his first, and the Copyright Office Review Board affirmed the denial of registration, agreeing that copyright protection does not extend to the creations of non-human entities.

[*603] Plaintiff timely challenged that decision in this Court, claiming that defendants’ denial of copyright registration to the work titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise,” was “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion and not in accordance with the law, unsupported by substantial evidence, and in excess of Defendants’ statutory authority,” in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”). The parties agree upon the key facts narrated above to focus, in the pending cross-motions for summary judgment, on the sole legal issue of whether a work autonomously generated by an AI system is copyrightable.

III. DISCUSSION

Under the Copyright Act of 1976, copyright protection attaches “immediately” upon the creation of “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression,” provided those works meet certain requirements. A copyright claimant can also register the work with the Register of Copyrights. Upon concluding that the work is indeed copyrightable, the Register will issue a certificate of registration, which, among other advantages, allows the claimant to pursue infringement claims in court. 17 U.S.C. §§ 410(a), 411(a)A valid copyright exists upon a qualifying work’s creation and “apart” from registration, however; a certificate of registration merely confirms that the copyright has existed all along. Conversely, if the Register denies an application for registration for lack of copyrightable subject matter—and did not err in doing so—then the work at issue was never subject to copyright protection at all.

In considering plaintiff’s copyright registration application as to “A Recent Entrance to Paradise,” the Register concluded that “this particular work will not support a claim to copyright” because the work lacked human authorship and thus no copyright existed in the first instance. By design in plaintiff’s framing of the registration application, then, the single legal question presented here is whether a work generated autonomously by a computer falls under the protection of copyright law upon its creation.

Plaintiff attempts to complicate the issues presented by devoting a substantial portion of his briefing to the viability of various legal theories under which a copyright in the computer’s work would transfer to him, as the computer’s owner; for example, by operation of common law property principles or the work-for-hire doctrine. These arguments concern to whom a valid copyright should have been registered, and in so doing put the cart before the horse.[2] By denying registration, the Register concluded that no valid copyright had ever existed in a work generated absent human involvement, leaving nothing at all to register and thus no question as to whom that registration belonged.

The only question properly presented, then, is whether the Register acted arbitrarily or capriciously or otherwise in violation of the APA in reaching that conclusion. The Register did not err in denying the copyright registration application presented by plaintiff. United States copyright law protects only works of human creation.

Plaintiff correctly observes that throughout its long history, copyright law has proven malleable enough to cover works created with or involving technologies developed long after traditional media of writings memorialized on paper. See, e.g., Goldstein v. California, 412 U.S. 546, 561 (1973) (explaining that the constitutional scope of Congress’s power to “protect the ‘Writings’ of ‘Authors’ ” is “broad,” such that “writings” is not “limited to script or printed material,” but rather encompasses “any physical rendering of the fruits of creative intellectual or aesthetic labor”); Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 58 (1884) (upholding the constitutionality of an amendment to the Copyright Act to cover photographs). In [*604] fact, that malleability is explicitly baked into the modern incarnation of the Copyright Act, which provides that copyright attaches to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). Copyright is designed to adapt with the times. Underlying that adaptability, however, has been a consistent understanding that human creativity is the sine qua non at the core of copyrightability, even as that human creativity is channeled through new tools or into new media. In Sarony, for example, the Supreme Court reasoned that photographs amounted to copyrightable creations of “authors,” despite issuing from a mechanical device that merely reproduced an image of what is in front of the device, because the photographic result nonetheless represented the original intellectual conceptions of the author. A camera may generate only a “mechanical reproduction” of a scene, but does so only after the photographer develops a “mental conception” of the photograph, which is given its final form by that photographer’s decisions like posing the subject in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories in said photograph, arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression, and from such disposition, arrangement, or representation” crafting the overall image. Human involvement in, and ultimate creative control over, the work at issue was key to the conclusion that the new type of work fell within the bounds of copyright.

Copyright has never stretched so far, however, as to protect works generated by new forms of technology operating absent any guiding human hand, as plaintiff urges here. Human authorship is a bedrock requirement of copyright.

That principle follows from the plain text of the Copyright Act. The current incarnation of the copyright law, the Copyright Act of 1976, provides copyright protection to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). The “fixing” of the work in the tangible medium must be done “by or under the authority of the author.” Id. § 101. In order to be eligible for copyright, then, a work must have an “author.”

To be sure, as plaintiff points out, the critical word “author” is not defined in the Copyright Act. “Author,” in its relevant sense, means “one that is the source of some form of intellectual or creative work,” “[t]he creator of an artistic work; a painter, photographer, filmmaker, etc.” Author, MERRIAM-WEBSTER UNABRIDGED DICTIONARY, https://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/unabridged/author (last visited Aug. 18, 2023); Author, OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/author_n (last visited Aug. 10, 2023). By its plain text, the 1976 Act thus requires a copyrightable work to have an originator with the capacity for intellectual, creative, or artistic labor. Must that originator be a human being to claim copyright protection? The answer is yes.

The 1976 Act’s “authorship” requirement as presumptively being human rests on centuries of settled understanding. The Constitution enables the enactment of copyright and patent law by granting Congress the authority to “promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” U.S. Const. art. 1, cl. 8. At the founding, both copyright and patent were conceived of as forms of property that the government was established to protect, and it was understood that recognizing exclusive rights in that property would further the public good by incentivizing individuals to create and invent. The act of human creation—and how to best encourage human individuals to engage in that creation, and thereby promote science and the [*605] useful arts—was thus central to American copyright from its very inception. Non-human actors need no incentivization with the promise of exclusive rights under United States law, and copyright was therefore not designed to reach them.

The understanding that “authorship” is synonymous with human creation has persisted even as the copyright law has otherwise evolved. The immediate precursor to the modern copyright law—the Copyright Act of 1909—explicitly provided that only a “person” could “secure copyright for his work” under the Act. Copyright under the 1909 Act was thus unambiguously limited to the works of human creators. There is absolutely no indication that Congress intended to effect any change to this longstanding requirement with the modern incarnation of the copyright law. To the contrary, the relevant congressional report indicates that in enacting the 1976 Act, Congress intended to incorporate the “original work of authorship” standard “without change” from the previous 1909 Act. See H.R. REP. NO. 94-1476, at 51 (1976).

The human authorship requirement has also been consistently recognized by the Supreme Court when called upon to interpret the copyright law. As already noted, in Sarony, the Court’s recognition of the copyrightability of a photograph rested on the fact that the human creator, not the camera, conceived of and designed the image and then used the camera to capture the image. See Sarony, 111 U.S. at 60. Similarly, in Mazer v. Stein, the Court delineated a prerequisite for copyrightability to be that a work “must be original, that is, the author’s tangible expression of his ideas.” 347 U.S. 201, 214 (1954). Goldstein v. California, too, defines “author” as “an ‘originator,’ ‘he to whom anything owes its origin,’ ” 412 U.S. at 561. In all these cases, authorship centers on acts of human creativity.

Accordingly, courts have uniformly declined to recognize copyright in works created absent any human involvement, even when, for example, the claimed author was divine. The Ninth Circuit, when confronted with a book “claimed to embody the words of celestial beings rather than human beings,” concluded that “some element of human creativity must have occurred in order for the Book to be copyrightable,” for “it is not creations of divine beings that the copyright laws were intended to protect.” Urantia Found. v. Kristen Maaherra, 114 F.3d 955, 958–59 (9th Cir. 1997) (finding that because the “members of the Contact Commission chose and formulated the specific questions asked” of the celestial beings, and then “select[ed] and arrange[d]” the resultant “revelations,” the Urantia Book was “at least partially the product of human creativity” and thus protected by copyright); see also Penguin Books U.S.A., Inc. v. New Christian Church of Full Endeavor, 96-cv-4126 (RWS), 2000 WL 1028634, at *2, 10–11 (S.D.N.Y. July 25, 2000) (finding a valid copyright where a woman had “filled nearly thirty stenographic notebooks with words she believed were dictated to her” by a “ ‘Voice’ which would speak to her whenever she was prepared to listen,” and who had worked with two human co-collaborators to revise and edit those notes into a book, a process which involved enough creativity to support human authorship); Oliver v. St. Germain Found., 41 F. Supp. 296, 297, 299 (S.D. Cal. 1941) (finding no copyright infringement where plaintiff claimed to have transcribed “letters” dictated to him by a spirit named Phylos the Thibetan, and defendant copied the same “spiritual world messages for recordation and use by the living” but was not charged with infringing plaintiff’s “style or arrangement” of those messages). Similarly, in Kelley v. Chicago Park District, the Seventh Circuit refused to “recognize[ ] copyright” in a cultivated garden, as doing so would “press[ ] too hard on the[ ] basic principle[ ]” that “[a]uthors of copyrightable works must be human.” 635 F.3d 290, 304–06 (7th Cir. 2011). The garden “ow[ed] [its] form to the forces of nature,” even if a human had originated the plan for the “initial arrangement of the plants,” and as such lay outside the bounds of copyright. Id. at 304. Finally, in Naruto [*606] v. Slater, the Ninth Circuit held that a crested macaque could not sue under the Copyright Act for the alleged infringement of photographs this monkey had taken of himself, for “all animals, since they are not human” lacked statutory standing under the Act. 888 F.3d 418, 420 (9th Cir. 2018). While resolving the case on standing grounds, rather than the copyrightability of the monkey’s work, the Naruto Court nonetheless had to consider whom the Copyright Act was designed to protect and, as with those courts confronted with the nature of authorship, concluded that only humans had standing, explaining that the terms used to describe who has rights under the Act, like “ ‘children,’ ‘grandchildren,’ ‘legitimate,’ ‘widow,’ and ‘widower[,]’ all imply humanity and necessarily exclude animals.” Plaintiff can point to no case in which a court has recognized copyright in a work originating with a non-human.

Undoubtedly, we are approaching new frontiers in copyright as artists put AI in their toolbox to be used in the generation of new visual and other artistic works. The increased attenuation of human creativity from the actual generation of the final work will prompt challenging questions regarding how much human input is necessary to qualify the user of an AI system as an “author” of a generated work, the scope of the protection obtained over the resultant image, how to assess the originality of AI-generated works where the systems may have been trained on unknown pre-existing works, how copyright might best be used to incentivize creative works involving AI, and more. See, e.g., Letter from Senators Thom Tillis and Chris Coons to Kathi Vidal, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and Shira Perlmutter, Register of Copyrights and Director of the U.S. Copyright Office (Oct. 27, 2022), https://www.copyright.gov/laws/hearings/Letter-to-USPTO-USCO-on-National-Commission-on-AI-1.pdf (requesting that the United States Patent and Trademark Office and the United States Copyright Office “jointly establish a national commission on AI” to assess, among other topics, how intellectual property law may best “incentivize future AI related innovations and creations”).

This case, however, is not nearly so complex. While plaintiff attempts to transform the issue presented here, by asserting new facts that he “provided instructions and directed his AI to create the Work,” that “the AI is entirely controlled by [him],” and that “the AI only operates at [his] direction”—implying that he played a controlling role in generating the work—these statements directly contradict the administrative record. Judicial review of a final agency action under the APA is limited to the administrative record, because it is black-letter administrative law that in an APA case, a reviewing court should have before it neither more nor less information than did the agency when it made its decision. Here, plaintiff informed the Register that the work was “[c]reated autonomously by machine,” and that his claim to the copyright was only based on the fact of his “[o]wnership of the machine.” The Register therefore made her decision based on the fact the application presented that plaintiff played no role in using the AI to generate the work, which plaintiff never attempted to correct. On the record designed by plaintiff from the outset of his application for copyright registration, this case presents only the question of whether a work generated autonomously by a computer system is eligible for copyright. In the absence of any human involvement in the creation of the work, the clear and straightforward answer is the one given by the Register: No.

Given that the work at issue did not give rise to a valid copyright upon its creation, plaintiff’s myriad theories for how ownership of such a copyright could have passed to him need not be further addressed. Common law doctrines of property transfer cannot be implicated where no property right exists to transfer in the first instance. The work-for-hire provisions of the Copyright Act, too, presuppose that an interest exists to be claimed. See 17 U.S.C. § 201(b) (“In the case of a work made for hire, the employer … owns all of the rights [*607[ comprised in the copyright.”).[3] Here, the image autonomously generated by plaintiff’s computer system was never eligible for copyright, so none of the doctrines invoked by plaintiff conjure up a copyright over which ownership may be claimed.

IV. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, defendants are correct that the Copyright Office acted properly in denying copyright registration for a work created absent any human involvement. Plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment is therefore denied and defendants’ cross-motion for summary judgment is granted.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Thaler

Question 1. What is the legal basis for the court’s holding in Thaler that human authorship is an essential part of a valid copyright claim?

Question 2. Which of these policy rationales does the Thaler court cite in support of its conclusion that U. S. copyright law protects only works of human creation?

Some things to consider when reading Théâtre D’opéra Spatial:

- This is a decision by the Review Board of the United States Copyright Office addressing the copyrightability of a work that the Board found to contain more than a de minimis amount of AI-generated content. Note that the Board is not saying that the work is uncopyrightable and cannot be registered, but rather that the human author must disclaim elements of the work that owe their origin to AI rather than a human author.

- The work was purportedly the first AI-generated image to win the 2022 Colorado State Fair’s annual fine art competition.

- Part of the applicant’s argument is that his action of entering a series of prompts into a text-to-picture [*608] artificial intelligence service constituted copyrightable “creative input.” What do you think of this argument? How does the use of generative AI tools like Midjourney compare to earlier technologies like Photoshop and spellcheck?

- The Board analogized the facts of the case to Kelley v. Chicago Park District. Recall that in Thaler the court did the same thing. Do you agree with this analogy?

- What do you think about the plaintiff’s policy argument that denying copyright protection to AI-generated material leaves a “void of ownership troubling to creators,” and the Board’s response to this argument?

Review Board Decision on Théâtre D’opéra Spatial

U.S. Copyright Office Review Board (Sept. 5, 2023)

SR # 1-11743923581; Correspondence ID: 1-5T5320R

Re: Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register Théâtre D’opéra Spatial

SUZANNE V. WILSON, General Counsel and Associate Register of Copyrights; MARIA STRONG, Associate Register of Copyrights and Director of Policy and International Affairs; JORDANA RUBEL, Assistant General Counsel

The Review Board of the United States Copyright Office (“Board”)[4] has considered Jason M. Allen’s (“Mr. Allen”) second request for reconsideration of the Office’s refusal to register a two-dimensional artwork claim in the work titled “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial” (“Work”). After reviewing the application, deposit copy, and relevant correspondence, along with the arguments in the second request for reconsideration, the Board affirms the Registration Program’s denial of registration. The Board finds that the Work contains more than a de minimis amount of content generated by artificial intelligence (“AI”), and this content must therefore be disclaimed in an application for registration. Because Mr. Allen is unwilling to disclaim the AI-generated material, the Work cannot be registered as submitted.

I. DESCRIPTION OF THE WORK

The Work is a two-dimensional artwork, reproduced below:

[*609]

II. ADMINISTRATIVE RECORD

On September 21, 2022, Mr. Allen filed an application to register a two-dimensional artwork claim in the Work. While Mr. Allen did not disclose in his application that the Work was created using an AI system, the Office was aware of the Work because it had garnered national attention for being the first AI-generated image to win the 2022 Colorado State Fair’s annual fine art competition. Because it was known to the Office that AI-generated material contributed to the Work, the examiner assigned to the application requested additional information about Mr. Allen’s use of Midjourney, a text-to-picture artificial intelligence service, in the creation of the Work. In response, Mr. Allen provided an explanation of his process, stating that he “input numerous revisions and text prompts at least 624 times to arrive at the initial version of the image.” He further explained that, after Midjourney produced the initial version of the Work, he used Adobe Photoshop to remove flaws and create new visual content and used Gigapixel AI to “upscale” the image, increasing its resolution and size. As a result of these disclosures, the examiner requested that the features of the Work generated by Midjourney be excluded from the copyright claim. Mr. Allen declined the examiner’s request and reasserted his claim to copyright in the features of the Work produced by an AI system. The Office refused to register the claim because the deposit for the Work did not “fix only [Mr. Allen’s] alleged authorship” but instead included “inextricably merged, inseparable contributions” from both Mr. Allen and Midjourney.

On January 24, 2023, Mr. Allen requested that the Office reconsider its initial refusal to register the Work, arguing that the examiner had misapplied the human authorship requirement and that public policy favored [*610] registration. After reviewing the Work in light of the points raised in the First Request, the Office reevaluated the claims and again concluded that the Work could not be registered without limiting the claim to only the copyrightable authorship Mr. Allen himself contributed to the Work. The Office explained that “the image generated by Midjourney that formed the initial basis for th[e] Work is not an original work of authorship protected by copyright.” The Office accepted Mr. Allen’s claim that human-authored “visual edits” made with Adobe Photoshop contained a sufficient amount of original authorship to be registered. However, the Office explained that the features generated by Midjourney and Gigapixel AI must be excluded as non-human authorship. Because Mr. Allen sought to register the entire work and refused to disclaim the portions attributable to AI, the Office could not register the claim.

In a letter submitted July 12, 2023, Mr. Allen requested that, pursuant to 37 C.F.R. § 202.5(c), the Office reconsider for a second time its refusal to register the Work. The Second Request presented several arguments. First, Mr. Allen argued that, in finding that the image generated by Midjourney lacks the human authorship essential for copyright protection, “the Office ignore[d] the essential element of human creativity required to create a work using the Midjourney program.” Mr. Allen argued that his “creative input” into Midjourney, which included “enter[ing] a series of prompts, adjust[ing] the scene, select[ing] portions to focus on, and dictat[ing] the tone of the image,” is “on par with that expressed by other types of artists and capable of Copyright protection.” He further contended that the fair use doctrine “would allow for registration of the work” because it “allows for transformative uses of copyrighted material.” Mr. Allen argued that, “[i]n this case, the underlying AI-generated work merely constitutes raw material which Mr. Allen has transformed through his artistic contributions.” Therefore, “regardless of whether the underlying AI-generated work is eligible for copyright registration, the entire Work in the form submitted to the copyright office should be accepted for registration.” Next, he asserted that, by refusing to register content generated via Midjourney and other generative AI platforms, “the Office is placing a value judgment on the utility of various tools,” and that denial of copyright protection for the output of such tools would result in a void of ownership. Finally, he objected to the Office’s registration requirements for works containing AI-generated content, stating that “[r]equiring creators to list each tool and the proportion of the work created with the tool would have a burdensome effect if enforced uniformly.”

III. DISCUSSION

After carefully examining the Work and considering the arguments made in the First and Second Requests, the Board finds that the Work contains more than a de minimis amount of AI-generated content, which must be disclaimed in an application for registration. Because Mr. Allen has refused to disclaim the material produced by AI, the Work cannot be registered as submitted.

A. Originality and the Human Authorship Requirement

Because copyright protection is only available for the creations of human authors, “the Office will refuse to register a [copyright] claim if it determines that a human being did not create the work.” U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, COMPENDIUM OF U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE PRACTICES § 306 (3d ed. 2021) (“COMPENDIUM (THIRD)”).

When analyzing AI-generated material, the Office must determine when a human user can be considered the “creator” of AI-generated output. In March 2023, the Office provided public guidance on registration [*611] of works created by a generative-AI system. The guidance explained that, in considering an application for registration, the Office will ask “whether the ‘work’ is basically one of human authorship, with the computer [or other device] merely being an assisting instrument, or whether the traditional elements of authorship in the work (literary, artistic, or musical expression or elements of selection, arrangement, etc.) were actually conceived and executed not by man but by a machine.” Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, 88 Fed. Reg. 16,190, 16,192 (Mar. 16, 2023) (“AI Registration Guidance”) (quoting U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, SIXTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE REGISTER OF COPYRIGHTS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 1965, 5 (1966)); see also AI Registration Guidance, 88 Fed. Reg. at 16,192 (asking “whether the AI contributions are the result of ‘mechanical reproduction’ or instead of an author’s ‘own original mental conception, to which [the author] gave visible form.’”) (quoting Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 60 (1884)). This analysis will be “necessarily case-by-case” because it will “depend on the circumstances, particularly how the AI tool operates and how it was used to create the final work.” AI Registration Guidance, 88 Fed. Reg. at 16,192.

If all of a work’s “traditional elements of authorship” were produced by a machine, the work lacks human authorship, and the Office will not register it. If, however, a work containing AI-generated material also contains sufficient human authorship to support a claim to copyright, then the Office will register the human’s contributions. In such cases, the applicant must disclose AI-generated content that is “more than de minimis.” Applicants may disclose and exclude such material by placing a brief description of the AI-generated content in the “Limitation of Claim” section on the registration application. The description may be as brief and generic as “[description of content] generated by artificial intelligence.” Applicants may provide additional information in the “Note to CO” field in the online application. Applicants are not required to list the AI tools used in the creation of the work.

B. Analysis

Because the Work here contains AI-generated material, the Board starts with an analysis of the circumstances of the Work’s creation, including Mr. Allen’s use of an AI tool. According to Mr. Allen, the Work was created by 1) initially generating an image using Midjourney (the “Midjourney Image”), 2) using Adobe Photoshop to “beautify and adjust various cosmetic details/flaws/artifacts, etc.” in the Midjourney Image, and 3) upscaling the image using Gigapixel AI. After considering the application, the deposit, and Mr. Allen’s correspondence, the Board concludes that the Work contains an amount of AI-generated material that is more than de minimis and thus must be disclaimed. Specifically, the Board concludes that the Midjourney Image, which remains in substantial form in the final Work, is not the product of human authorship. In reaching this conclusion, the Board does not decide whether Mr. Allen’s adjustments made in Adobe Photoshop would be copyrightable on their own because the Board lacks sufficient information to make that determination. The Board also does not consider Mr. Allen’s use of Gigapixel AI because he concedes that Gigapixel AI “doesn’t introduce new, original elements into the image” and that “the enlargement process undertaken by Gigapixel AI does not equate to authorship.”[*612]

In his Second Request, Mr. Allen asserts a number of arguments in support of his claim. He argues that his use of Midjourney allows him to claim authorship of the image generated by the service because he provided “creative input” when he “entered a series of prompts, adjusted the scene, selected portions to focus on, and dictated the tone of the image.” As explained in his correspondence, Mr. Allen created a text prompt that began with a “big picture description” that “focuse[d] on the overall subject of the piece.” He then added a second “big picture description” to the prompt text “as a way of instructing the software that Mr. Allen is combining two ideas.” Next, he added “the overall image’s genre and category,” “certain professional artistic terms which direct the tone of the piece,” “how lifelike [Mr. Allen] wanted the piece to appear,” a description of “how colors [should be] used,” a description “to further define the composition,” “terms about what style/era the artwork should depict,” and “a writing technique that Mr. Allen has established from extensive testing” that would make the image “pop.” He then “append[ed the prompt] with various parameters which further instruct[ed] the software how to develop the image,” resulting in a final text prompt that was “executed . . . into Midjourney to complete the process” and resulted in the creation of the Midjourney Image above.

In the Board’s view, Mr. Allen’s actions as described do not make him the author of the Midjourney Image because his sole contribution to the Midjourney Image was inputting the text prompt that produced it. Although Mr. Allen describes “input[ing] numerous revisions and text prompts at least 624 times” before producing the Midjourney Image, the steps in that process were ultimately dependent on how the Midjourney system processed Mr. Allen’s prompts. According to Midjourney’s documentation, prompts “influence” what the system generates and are “interpret[ed]” by Midjourney and “compared to its training data.” As the Office has explained, “Midjourney does not interpret prompts as specific instructions to create a particular expressive result,” because “Midjourney does not understand grammar, sentence structure, or words like humans.” It is the Office’s understanding that, because Midjourney does not treat text prompts as direct instructions, users may need to attempt hundreds of iterations before landing upon an image they find satisfactory. This appears to be the case for Mr. Allen, who experimented with over 600 prompts before he “select[ed] and crop[ped] out one ‘acceptable’ panel out of four potential images … (after hundreds were previously generated).” As the Office described in its March guidance, “when an AI technology receives solely a prompt from a human and produces complex written, visual, or musical works in response, the ‘traditional elements of authorship’ are determined and executed by the technology—not the human user.” AI Registration Guidance, 88 Fed. Reg. at 16,192. And because the authorship in the Midjourney Image is more than de minimis, Mr. Allen must exclude it from his claim. See id. at 16,193. Because Mr. Allen has refused [*613] to limit his claim to exclude its non-human authorship elements, the Office cannot register the Work as submitted.

The Board finds that Mr. Allen’s remaining arguments regarding elements of authorship in the Work are unpersuasive. First, he argues that the Office’s position “ignores the essential element of human creativity required to create a work using the Midjourney program,” and that his creative choices in operating Midjourney make him the author of resulting output. The Board acknowledges that the process of prompting can involve creativity—after all, “some prompts may be sufficiently creative to be protected by copyright” as literary works. But that does not mean that providing text prompts to Midjourney “actually form[s]” the generated images. Instead, Mr. Allen is closer to the plaintiff in Kelley v. Chicago Park District who sought to claim copyright in a “living garden.” 635 F.3d 290 (7th Cir. 2011). In that case, the court rejected the authorship claim because, as is true here, the plaintiff’s actions did not amount to creative control of the claimed elements of the work. As the Seventh Circuit further explained, while “copyright’s prerequisites of authorship and fixation are broadly defined, … the law must have some limits.”

Second, the Board rejects Mr. Allen’s policy argument that denying copyright protection to AI-generated material leaves a “void of ownership troubling to creators.” The Constitution and the Copyright Act define the works that are entitled to copyright protection, and expressly exclude certain subject matter. To be copyrightable, a work must qualify as an “original work of authorship,” which excludes works produced by non-humans. The fact that not all works will satisfy this standard does not create a “troubling” void of ownership. The Office administers the copyright laws as enacted by Congress and cannot exceed the bounds set by Congress and the Constitution.

Third, the Board rejects Mr. Allen’s argument that requiring AI-generated material to be excluded from the application for the Work improperly “plac[es] a value judgment on the utility of various tools.” The disclosure of AI-generated material is “information regarded by the Register of Copyrights as bearing upon the preparation or identification of the work or the existence, ownership, or duration of the copyright.” 17 U.S.C. § 409(10). As the Office’s guidance on works containing AI-generated material explained, the Copyright Act permits the Register to identify such information and require its disclosure in copyright applications. This requirement is not a value judgment; it is a recognition of the fact that “[h]uman authorship is a bedrock requirement of copyright.”

Fourth, the Board rejects Mr. Allen’s suggestion that the doctrine of “fair use” is relevant to the determination of whether a work is copyrightable. See Second Request at 1, 9–11 (arguing that AI-generated material “merely constitutes raw material which Mr. Allen has transformed”) (citing Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013)). Fair use is a legal doctrine that permits the unauthorized use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances; it does not address copyrightability, but rather use. To the extent Mr. Allen argues by analogy that his visual edits are “transformative,” and thus, copyrightable, the Board agrees that human-authored modifications of AI-generated material may protected by copyright. But the Office cannot register Mr. Allen’s human contributions if he does not limit his claim with respect to the AI-generated material.

IV. CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, the Review Board of the United States Copyright Office affirms the refusal [*614] to register the copyright claim in the Work. Pursuant to 37 C.F.R. § 202.5(g), this decision constitutes final agency action regarding Mr. Allen’s September 2022 application.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Théâtre D’opéra Spatial

Question 1. Which of the following will the Copyright Office register as a copyrighted work?

Question 2. In Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, how did the Board respond to the policy argument that denying copyright protection to AI-generated material leaves a “void of ownership troubling to creators.”

Some things to consider when reading Stability AI:

- In this case graphic artists are suing multiple defendants for their involvement in the creation and use of Stable Diffusion, which the court characterizes as an AI software product that provides “image-generating services,” and which the plaintiffs allege was “trained” using the plaintiffs’ copyrighted works without their authorization.

- The decision illustrates some of the obstacles that face copyright owners seeking to enforce their copyrights in this context. The court found their complaint to be “defective in numerous respects,” and largely granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss, while giving the plaintiffs permission to amend their complaint to provide clarity regarding their theories of infringement.

- Note the court’s response to the plaintiffs’ claims that both the AI product and its output images are infringing derivative works.

- Do you think the defendants might be able to successfully invoke a fair use defense?

- This is one of many lawsuits alleging copyright infringement that have been filed on behalf of artists and authors against AI platforms, see, e.g., Authors Guild et al. v. OpenAI, Sarah Silverman et al. v. OpenAI and Meta, Getty Images v. Stability AI, and Universal Music Group et al. v. Anthropic.

[*615] Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd.

700 F.Supp.3d 853 (N.D. Cal. 2023)

WILLIAM H. ORRICK, United States District Judge

Artists Sarah Anderson, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz filed this putative class action on behalf of themselves and other artists to challenge the defendants’ creation or use of Stable Diffusion, an artificial intelligence (“AI”) software product. Plaintiffs allege that Stable Diffusion was “trained” on plaintiffs’ works of art to be able to produce Output Images “in the style” of particular artists. The three sets of defendants ((i) Stability AI Ltd. and Stability AI, Inc. (“Stability”); (ii) DeviantArt, Inc.; and (iii) Midjourney, Inc.) have each filed separate motions to dismiss. Finding that the Complaint is defective in numerous respects, I largely GRANT defendants’ motions to dismiss. Plaintiffs are given leave to amend to provide clarity regarding their theories of how each defendant separately violated their copyrights, removed or altered their copyright management information, or violated their rights of publicity and plausible facts in support.

BACKGROUND

Plaintiffs allege that Stability created and released in August 2022 a “general-purpose” software program called Stable Diffusion under a “permission open-source license.” Stability is alleged to have “downloaded of otherwise acquired copies of billions of copyrighted images without permission to create Stable Diffusion,” known as “training images.” Over five billion images were scraped (and thereby copied) from the internet for training purposes for Stable Diffusion through the services of an organization (LAION, Large-Scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network) paid by Stability. Stability’s founder and CEO “publicly acknowledged the importance of using licensed training images, saying that future versions of Stable Diffusion would be based on ‘fully licensed’ training images. But for the current version, he took no steps to obtain or negotiate suitable licenses.”

Stable Diffusion is alleged to be a “software library” providing “image-generating services” to products produced and maintained by the defendants including “DreamStudio, DreamUp, and on information and belief, the Midjourney Product.” Consumers use these products by entering text prompts into the programs to create images “in the style” of artists. The new images are created “through a mathematical process” that are based entirely on the training images and are “derivative” of the training images. Plaintiffs admit that “[i]n general, none of the Stable Diffusion output images provided in response to a particular Text Prompt is likely to be a close match for any specific image in training data. This stands to reason: the use of conditioning data to interpolate multiple latent images means that the resulting hybrid image will not look exactly like any of the Training Images that have been copied into these latent images.” Plaintiffs also allege that “[e]very output image from the system is derived exclusive from the latent images, which are copies of copyrighted images. For these reasons, every hybrid image is necessarily a derivative work.”

DreamStudio is Stability’s product, also released in August 2002; it functions as an “user interface” accessing “a trained version of Stable Diffusion.”

Defendant DeviantArt was founded in 2000 and has primarily been known as an “online community” where digital artists post and share their work. Deviant Art released its “DreamUp” product in November 2022. [*616] DreamUp is a commercial product that relies on Stable Diffusion to produce images and is only available to customers who pay DeviantArt. Plaintiffs allege that at least one LAION dataset that was incorporated into Stable Diffusion for training images (the “aesthetic dataset”) was procured by scraping primarily 100 websites, including DeviantArt’s site. As a result, plaintiffs allege that Stability copied thousands and possible millions of training images from DeviantArt created by artists and other DeviantArt subscribers without licensing their works of art.

Defendant Midjourney, based in San Francisco, created and distributes the “Midjourney Product.” The Midjourney Product was launched in beta form in July 2022, and is alleged to be a commercial product that produces images in response to text prompts in the same manner as DreamStudio and DreamUp. Plaintiffs allege that the Midjourney product uses Stable Diffusion but also that it was “trained on a subset of the images used to train Stable Diffusion.” The Midjourney Product is offered to online users of the internet-chat system Discord, as well as through an app, for a service fee. Midjourney’s CEO has stated that Midjourney used large open data sets, thereby “implying” that Midjourney used the LAION datasets for training. In August 2022, Midjourney released a beta version using Stable Diffusion.

Plaintiff Anderson resides in Oregon and is a full-time cartoonist and illustrator. Plaintiffs allege that Anderson “has created and owns a copyright interest in over two hundred Works included in the Training Data,” and has registered or applied “for an owns copyright registrations for sixteen collections that include Works used as Training Images.” Plaintiff McKernan resides in Tennessee and is a full-time artist. McKernan is alleged to have “created and owns a copyright interest in over thirty Works used as Training Images.” Plaintiff Ortiz resides in California and is a full-time artist. Ortiz is alleged to have “created and owns a copyright interest in at least twelve Works that were used as Training Images.”

Plaintiffs assert the following claims against all three sets of defendants: (1) Direct Copyright Infringement, 17 U.S.C. § 106; (2) Vicarious Copyright Infringement, 17 U.S.C. § 106; (3) violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 1201-1205 (“DMCA”); (4) violation of the Right to Publicity, Cal. Civil Code § 3344; (5) violation of the Common Law Right of Publicity; (6) Unfair Competition, Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17200; and (7) Declaratory Relief.

LEGAL STANDARD

Under FRCP 12(b)(6), a district court must dismiss a complaint if it fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. To survive a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, the plaintiff must allege “enough facts to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face.” Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 570 (2007).

DISCUSSION

I. MOTIONS TO DISMISS

Each of the defendants separately move to dismiss, but raise substantially similar arguments addressed collectively below.

A. Copyright – Counts I & II

2. Identifying Infringed Works

[*617] As to Anderson, defendants argue that she cannot proceed with her copyright infringement allegations unless she identifies with specificity each of her registered works that she believes were used as Training Images for Stable Diffusion. In the Complaint, Anderson alleges that she “has created and owns a copyright interest in over two hundred Works included in the Training Data” and that “[e]xamples of Ms. Andersen’s Works included in the Training Data can be found here: https://haveibeentrained.com/?search_text=sarah% 20andersen.cites.”

Defendants contend that those allegations are insufficient and argue that Anderson should be required to identify which specific works from which of her registered collections she believes were copied into the LAION datasets and ended up as Training Images for Stable Diffusion.

Anderson does not identify which of her specific works covered by a registration were used as Training Images but relies on the output of a search of her name on the “ihavebeentrained.com” site to support the plausibility and reasonableness of her belief that her works were, in fact, used in the LAION datasets and training for Stable Diffusion. She attests that her review of the output pages from that search confirms that some of her registered works were used as Training Images. That is a sufficient basis to allow her copyright claims to proceed at this juncture, particularly in light of the nature of this case, i.e., that LAION scraped five billion images to create the Training Image datasets. At this juncture, the plausible inferences are that all of Anderson’s works that were registered as collections and were online were scraped into the training datasets. Her assertions regarding the results of her search on the “haveibeentrained” site supports that inference and makes it reasonable for this case. While defendants complain that Anderson’s reference to search results on the “haveibeentrained” website is insufficient, as the output pages show many hundreds of works that are not identified by specific artists, defendants may test Anderson’s assertions in discovery.

3. Direct Infringement Allegations Against Stability

Plaintiffs’ primary theory of direct copyright infringement is based on Stability’s creation and use of “Training Images” scraped from the internet into the LAION datasets and then used to train Stable Diffusion. Plaintiffs have adequately alleged direct infringement based on the allegations that Stability “downloaded or otherwise acquired copies of billions of copyrighted images without permission to create Stable Diffusion,” and used those images (called “Training Images”) to train Stable Diffusion and caused those “images to be stored at and incorporated into Stable Diffusion as compressed copies.” In its “Preliminary Statement” in support of its motion to dismiss, Stability opposes the truth of plaintiffs’ assertions. However, even Stability recognizes that determination of the truth of these allegations – whether copying in violation of the Copyright Act occurred in the context of training Stable Diffusion or occurs when Stable Diffusion is run – cannot be resolved at this juncture. Stability does not otherwise oppose the sufficiency of the allegations supporting Anderson’s direct copyright infringement claims with respect to the Training Images.

Stability’s motion to dismiss Count I for direct copyright infringement is DENIED.

4. Direct Infringement Allegations Against DeviantArt

Plaintiffs fail to allege specific plausible facts that DeviantArt played any affirmative role in the scraping and using of Anderson’s and other’s registered works to create the Training Images. The Complaint, instead, admits that the scraping and creation of Training Images was done by LAION at the direction of Stability and that Stability used the Training Images to train Stable Diffusion. What DeviantArt is specifically alleged to [*518] have done is be a primary “source” for the “LAION-Aesthetic dataset” created to train Stable Diffusion. That, however, does not support a claim of direct copyright infringement by DeviantArt itself.

In opposition, plaintiffs offer three theories of DeviantArt’s direct infringement:

(1) direct infringement by distributing Stable Diffusion, which contains compressed copies of the training images, as part of DeviantArt’s DreamUp AI imaging product;

(2) direct infringement by creating and distributing their DreamUp, which is itself an infringing derivative work; and

(3) generating and distributing output images which are infringing derivative works.

In support, plaintiffs point to their allegations that: “Stable Diffusion has been used as a Software Library within” DreamUp; “DreamUp is a commercial product that relies on Stable Diffusion to produce images”; “DreamUp is a web-based app that generates images in response to Text Prompts. Like DreamStudio, DreamUp relies on Stability’s Stable Diffusion software as its underlying software engine”; that DeviantArt embraced “Stable Diffusion by incorporating it into their website via the DreamUp app,”; and DeviantArt decided to use “Stable Diffusion because it’s the only option for us to take an open source [software engine] and modify it.”

DeviantArt vigorously disputes the assertions – made throughout the Complaint – that “embedded and stored compressed copies of the Training Images” are contained within Stable Diffusion. DeviantArt (and Stability and Midjourney) argue that those assertions are implausible given plaintiffs’ allegation that the training dataset was comprised of five billion images; five billion images could not possibly be compressed into an active program. Defendants also claim that the “compressed copies” allegations are contradicted by plaintiffs’ descriptions of the diffusion process in the Complaint. Those descriptions admit that the diffusion process involves not copying of images, but instead the application of mathematical equations and algorithms to capture concepts from the Training Images. Finally, defendants rely heavily on plaintiffs’ admission that, “[i]n general, none of the Stable Diffusion output images provided in response to a particular Text Prompt is likely to be a close match for any specific image in the training data.” In light of that, defendants argue that plaintiffs cannot plausibly plead copying in violation of the Copyright Act based on Output Images.

Turning to the first theory of direct copyright infringement and the plausibility of plaintiffs’ assertion that Stable Diffusion contains “compressed copies” of the Training Images and DeviantArt’s DreamUp product utilizes those compress copies, DeviantArt is correct that the Complaint is unclear. As noted above, the Complaint repeatedly alleges that Stable Diffusion contains compressed copies of registered works. But the Complaint also describes the diffusion practice as follows:

Because a trained diffusion model can produce a copy of any of its Training Images—which could number in the billions—the diffusion model can be considered an alternative way of storing a copy of those images. In essence, it’s similar to having a directory on your computer of billions of JPEG image files. But the diffusion model uses statistical and mathematical methods to store these images in an even more efficient and compressed manner.

[*619] Plaintiffs will be required to amend to clarify their theory with respect to compressed copies of Training Images and to state facts in support of how Stable Diffusion – a program that is open source, at least in part – operates with respect to the Training Images. If plaintiffs contend Stable Diffusion contains “compressed copies” of the Training Images, they need to define “compressed copies” and explain plausible facts in support. And if plaintiffs’ compressed copies theory is based on a contention that Stable Diffusion contains mathematical or statistical methods that can be carried out through algorithms or instructions in order to reconstruct the Training Images in whole or in part to create the new Output Images, they need to clarify that and provide plausible facts in support.

Depending on the facts alleged on amendment, DeviantArt (and Midjourney) may make a more targeted attack on the direct infringement contentions. It is unclear, for example, if Stable Diffusion contains only algorithms and instructions that can be applied to the creation of images that include only a few elements of a copyrighted Training Image, whether DeviantArt or Midjourney can be liable for direct infringement by offering their clients use of the Stable Diffusion “library” through their own apps and websites. But if plaintiffs can plausibly plead that defendants’ AI products allow users to create new works by expressly referencing Anderson’s works by name, the inferences about how and how much of Anderson’s protected content remains in Stable Diffusion or is used by the AI end-products might be stronger.[5]

In addition to providing clarity regarding their definition of and theory with respect to the inclusion of compressed copies of Training Images in Stable Diffusion, plaintiffs shall also provide more facts that plausibly show how DeviantArt is liable for direct copyright infringement when, according to plaintiffs’ current allegations, DeviantArt simply provides its customers access to Stable Diffusion as a library. Plaintiffs do cite testimony from DeviantArt’s CEO that DeviantArt uses Stable Diffusion because Stability allowed DeviantArt to “modify” Stable Diffusion. The problem is that there are no allegations what those modifications might be or why, given the structure of Stable Diffusion, any compressed copies of copyrighted works that may be present in Stable Diffusion would be copied within the meaning of the Copyright Act by DeviantArt or its users when they use DreamUp. Nor do plaintiffs provide plausible facts regarding DeviantArt “distributing” Stable Diffusion to its users when users access DreamUp through the app or through DeviantArt’s website.

That leaves plaintiffs’ third theory of direct infringement; that DreamUp produces “Output Images” that are all infringing derivative works.[6] DeviantArt argues that to adequately plead this claim, plaintiffs must allege the Output Images are substantially similar to the protected works but they cannot do so given plaintiffs’ repeated admission that “none of the Stable Diffusion output images provided in response to a particular Text Prompt is likely to be a close match for any specific image in the training data.”

A problem for plaintiffs is that [their] theory regarding compressed copies and DeviantArt’s copying need to be clarified and adequately supported by plausible facts. The other problem for plaintiffs is that it is simply not plausible that every Training Image used to train Stable Diffusion was copyrighted (as opposed to copyrightable), or that all DeviantArt users’ Output Images rely upon (theoretically) copyrighted Training Images, and therefore all Output images are derivative images.

Even if that clarity is provided and even if plaintiffs narrow their allegations to limit them to Output Images that draw upon Training Images based upon copyrighted images, I am not convinced that copyright claims based a derivative theory can survive absent “substantial similarity” type allegations. The cases plaintiffs [*620] rely on appear to recognize that the alleged infringer’s derivative work must still bear some similarity to the original work or contain the protected elements of the original work. See, e.g., Jarvis v. K2 Inc., 486 F.3d 526, 532 (9th Cir. 2007) (finding works were derivative where plaintiff “delivered the images to K2 in one form, and they were subsequently used in the collage ads in a quite different (though still recognizable) form. The ads did not simply compile or collect Jarvis’ images but rather altered them in various ways and fused them with other images and artistic elements into new works that were based on—i.e., derivative of—Jarvis’ original images.”) (emphasis added); ITC Textile Ltd. v. Wal-Mart Stores Inc., No. CV122650JFWAJWX, 2015 WL 12712311, at *5 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 16, 2015) (“Accordingly, even if Defendants did modify them slightly, such modifications are not sufficient to avoid infringement in a direct copying case…. Thus, the law is clear that in cases of direct copying, the fact that the final result of defendant’s work differs from plaintiff’s work is not exonerating.”) (emphasis added); see also Litchfield v. Spielberg, 736 F.2d 1352, 1357 (9th Cir. 1984) (“a work is not derivative unless it has been substantially copied from the prior work”); Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., 804 F.3d 202, 225 (2d Cir. 2015) (“derivative works over which the author of the original enjoys exclusive rights ordinarily are those that re-present the protected aspects of the original work, i.e., its expressive content”).

Defendants make a strong case that I should dismiss the derivative work theory without leave to amend because plaintiffs cannot plausibly allege the Output Images are substantially similar or re-present protected aspects of copyrighted Training Images, especially in light of plaintiffs’ admission that Output Images are unlikely to look like the Training Images. But other parts of plaintiffs’ Complaint allege that Output Images can be so similar to plaintiff’s styles or artistic identities to be misconstrued as “fakes.” Once plaintiffs amend, hopefully providing clarified theories and plausible facts, this argument may be re-raised on a subsequent motion to dismiss.

DeviantArt’s motion to dismiss Claim I is GRANTED with leave to amend.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Stability AI

Question 1. Having survived a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, which of the following will the plaintiffs in Stability AI likely attempt to establish in order to move forward with their claims of copyright infringement?

Some things to consider when reading Ross:

- In this decision a district court denies both parties’ motions for summary judgment in a case in which [*621] the owner of Westlaw sued Ross, an AI startup, for copyright infringement, largely based on the court’s determination that “many of the critical facts in this case remain genuinely disputed.”

- Westlaw has no copyright in the reported judicial decisions (see the section of this casebook on government works), but does claim copyright in its headnotes and Key Number System. Note that the question of whether this Westlaw-generated content is copyrighted—and if so, to what extent—is disputed, which is one reason the court denied summary judgment.

- The case gives some insight into the mechanics of creating an AI model.

- The court finds that at least portions of the headnotes were actually copied, and thus it appears that Ross will likely be found liable for copyright infringement if the headnotes are sufficiently creative and distinct from the judicial opinions upon which they are based, unless Ross can successfully invoke the affirmative defense of fair use.

- Although the court finds that the question of fair use must ultimately go to the jury to resolve certain factual questions, the court does engage in some application of the four fair use factors to Ross’s copying. Note the court’s apparent focus on “transformativeness,” and its decision not to “overread” Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith.

- The court discusses the implications of the “intermediate copying caselaw” in relation to the question of transformativeness.

- The court discusses the public benefits Ross’s copying will likely produce, and the parties’ “competing narratives of public benefit.”

- In addition to addressing generative AI, this case offers a good recap of many of the key doctrines throughout copyright law, including originality, idea/expression, copying in fact, substantial similarity, fair use, and secondary liability.

Thomson Reuters Enter. Ctr. GmbH v. Ross Intel. Inc.

694 F.Supp.3d 467 (D. Del. 2023)

BIBAS, Circuit Judge.

Facts can be messy even when parties wish they were not. But summary judgment is proper only if factual messes have been tidied. Courts cannot clean them up.

Thomson Reuters, a media company, owns a well-known legal research platform, Westlaw. It alleges that Ross, an artificial intelligence startup, illegally copied important content from Westlaw. Thomson Reuters thus seeks to recover from Ross. Both sides move for summary judgment on a variety of claims and defenses. But many of the critical facts in this case remain genuinely disputed. So I largely deny Thomson Reuters’s and Ross’s motions for summary judgment.

I. Background

Many facts are disputed, but the basic story is not. Thomson Reuters’s Westlaw platform compiles judicial opinions according to its Key Number System. That system organizes opinions by the type of law. Westlaw also adds “headnotes”: short summaries of points of law that appear in the opinion. Each headnote is tied to a key number. Clicking on the headnote takes the user to the corresponding passage in the opinion. Clicking [*622] on the key number takes the user to a list of cases that make the same legal point. Westlaw has a registered copyright on its “original and revised text and compilation of legal material,” which includes its headnotes and Key Number System.

Ross Intelligence is a legal-research industry upstart. It sought to create a “natural language search engine” using machine learning and artificial intelligence. It wanted to “avoid human intermediated materials.” Users would enter questions and its search engine would spit out quotations from judicial opinions—no commentary necessary.

To leverage machine learning, Ross needed legal material to train the machine. At first, it tried to get a license to use Westlaw, but Thomson Reuters does not let users use Westlaw to develop a competing platform. So Ross turned to a third-party legal-research company, LegalEase Solutions.

Ross told LegalEase to create memos with legal questions and answers. The questions were meant to be those “that a lawyer would ask,” and the answers were direct quotations from legal opinions. The so-called Bulk Memo Project produced about 25,000 question-and-answer sets. Each memo had one question plus four to six answers and rated each answer’s relevance. LegalEase created the memos both manually and, for a time, with the help of a text-scraping bot.

Ross says it converted the LegalEase memos into usable machine-learning training data. That involved first encoding the written language as numerical data and then running the data through a “Featurizer” that “performed various mathematical … calculations on the text.”

The core of this suit stems from the Bulk Memo Project. Thomson Reuters says the questions were essentially headnotes with question marks at the end. Ross admits that the headnotes “influenced” the questions but says lawyers ultimately drafted them, instead of copying them. Though Thomson Reuters contends that all 25,000 are copies, it has moved for summary judgment on just 2,830. It says LegalEase’s copying of those 2,830 is undisputed because Ross’s own expert admitted it.

Beyond the Bulk Memo Project, LegalEase provided Ross with two other relevant services. First, LegalEase sent Ross a list of 91 legal topics from Westlaw’s Key Number System. Ross admits that it “considered” these topics when creating its own set of 38 topics that were used in an experimental “Classifier Project.” But it ultimately abandoned the Project. LegalEase also sent Ross 500 judicial opinions, including Westlaw’s headnotes, key numbers, and other annotations. Ross says it did nothing with these opinions.

In this opinion, I address five summary-judgment motions. Thomson Reuters has moved for summary judgment on its copyright-infringement claim (limited to the 2,830 memos mentioned), and both sides have moved for summary judgment on Ross’s fair-use defense. Thomson Reuters has also moved for summary judgment on its tortious-interference-with-contract claim, and Ross has counter-moved on its preemption defense to that claim.

II. Copyright Infringement

A copyright-infringement claim has three elements: ownership of a valid copyright, actual copying, and substantial similarity. See Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 361 (1991). Here, all three elements are at least partly disputed. But the dispute over the second element is legal, so I can decide it now. [*623] And because Ross hired LegalEase to do the copying (if there was any), Thomson Reuters also couches its argument in terms of direct, contributory, and vicarious liability. So after addressing the three infringement elements, I will consider each of these liability theories as well.

A. The parties still dispute breadth and validity of Westlaw’s copyright

Ross bets a good chunk of its infringement defense on Westlaw’s being registered as a compilation. Ross’s theory is this: because Westlaw has just one copyright registration, comprising hundreds of thousands of headnotes and key numbers, copying a mere few thousand is not enough for infringement.

Ross’s gamble does not pay off. A copyright in a compilation extends to the copyrightable pieces of that compilation. And when the author of a compilation presents facts through his own original words, “[o]thers may copy the underlying facts from the publication, but not the precise words used to present them.” Feist, 499 U.S. at 348. Plus, though a plaintiff must have a registration to bring a federal suit for infringement, it can sue on all protected components of that one registration. 2 David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright § 7.16(B)(5)(c) (2023).

The cases Ross cites are the exceptions that prove the rule. In those cases, the copyright holder owned only the compilation. In one case cited, the plaintiff had a compilation copyright in the organization and selection of state legal forms. Ross, Brovins & Oehmke, P.C. v. Lexis Nexis Grp., 463 F.3d 478, 480 (6th Cir. 2006). Though the underlying entries were in the public domain, the organizer’s exact selection and arrangement were copyrightable. Even though the defendant copied and compiled 61% of the forms from the plaintiff’s compilation, there was no infringement because the defendant’s compilation was not the “same selection.” So in these cases, the plaintiffs owned “thin” copyrights: other than their selection and arrangement choices, none of their compilations’ components were protectable.

Here, only the Key Number System aligns with the compilation caselaw: It is Westlaw’s method of organizing and arranging judicial opinions. So Thomson Reuters could have a valid copyright in this method of arrangement but not in the underlying opinions. That said, to qualify for copyright protection, the manner of rearranging and organizing the unprotectable underlying works must constitute more than a minimal contribution. This threshold for originality is low, but the parties dispute facts needed to figure out if the System clears the bar.

Thomson Reuters alleges that employees make creative organizing decisions to update and maintain the System and that the System is unique among its competition. But Ross replies that the System is unoriginal because most of the organization decisions are made by a rote computer program and the high-level topics largely track common doctrinal topics taught as law school courses. And although Thomson Reuters’s registered copyright could protect its Key Number System, the jury needs to decide its originality, whether it is in fact protected, and how far that protection extends.

In contrast, the headnotes are not aptly described by the compilation caselaw. Headnotes are just short written works, authored by Thomson Reuters, so they could receive standalone, individual copyright protection. See 17 U.S.C. § 103. This distinguishes Thomson Reuters’s copyright in its headnotes from the “thin,” compilation-only copyrights in Ross’s examples. So I must consider the alleged headnote copyright infringement at the level of each individual headnote, rather than at the level of the entire Westlaw compilation.

[*624] That said, Thomson Reuters’s allegedly original expression in its headnotes still reflects uncopyrightable judicial opinions. So the strength of its copyright depends on how much the headnotes overlap with the opinions. Closely hewing differs from copying: If a headnote merely copies a judicial opinion, it is uncopyrightable. But if it varies more than trivially, then Westlaw owns a valid copyright.

The parties dispute how Thomson Reuters develops its headnotes and how closely those headnotes resemble uncopyrightable opinions. Thomson Reuters points to evidence that its headnotes are original representations of its attorney-editors’ views—summarizing the most important case facts, highlighting key issues, and describing the holdings. Ross, though, presents evidence that Thomson Reuters’s protocols required headnotes to follow or closely mirror the language of judicial opinions. This leaves a genuine factual dispute about how original the headnotes are. And this fact will serve double duty: it affects the strength and extent of Thomson Reuters’s copyright, and it also goes to whether Ross was copying the headnotes or the opinions themselves.

In sum, I cannot decide the first element of Thomson Reuters’s copyright infringement claim at summary judgment.

B. As a matter of law, Ross actually copied at least portions of the Bulk Memos

Next, Thomson Reuters must show that Ross (or LegalEase) “actually copied” its copyrighted work. There are two ways to show actual copying: Thomson Reuters can present direct evidence. Or it can present circumstantial evidence demonstrating that Ross or LegalEase had access to the copyrighted work and that their work contains similarities probative of copying.

Thomson Reuters presents both. LegalEase admitted to copying at least portions of the headnotes directly. As for circumstantial evidence, Ross does not dispute that LegalEase had access to Westlaw, which included access to headnotes. Though the similarities between Thomson Reuters’s and Ross’s work might not be substantial (that is a jury question), no reasonable jury could say that the similarities are not at least probative of some copying. And while Ross argues that any copying that occurred was miniscule in the grand scheme of the compilation, that framing misses the mark for the reasons given above. So Thomson Reuters has satisfied the actual-copying element as a matter of law.

C. Substantial similarity must go to the jury

The last element of direct infringement is substantial similarity. Substantial similarity asks whether the ordinary observer, unless he set out to detect the disparities in the two works, would be disposed to overlook them, and regard their aesthetic appeal as the same. In other words, I ask whether an ordinary person would view the two works as basically the same.