Chapter 2: Requirements for Copyrightability under the 1976 Act

[*3]In order for a “work” (e.g., a book, musical composition, movie, computer program, or sculpture) to be copyrighted under the 1976 Act, it must satisfy several criteria. In brief, it must be (1) copyrightable subject matter that is (2) “original” and (3) “fixed” in a tangible medium of expression. The following sections address these three requirements.

A. Copyrightable Subject Matter

The 1976 Act explicitly defines the scope of copyrightable subject matter, and provides a non-exhaustive list comprising eight categories of copyrightable subject matter. In particular, Section 102(a) of the Act sets forth a positive definition of subject matter that is potentially eligible for copyright protection (so long as all of the other requirements of copyrightability are satisfied). Section 102(b), on the other hand, provides a negative definition of subject matter that is ineligible for copyright protection, regardless of whether it meets the other requirements of copyrightability.

Section 102(a) begins by broadly defining the scope of copyrightable subject matter as encompassing “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.” Note that this definition explicitly recites the requirements of “originality,” “fixation,” and “work of authorship.” These requirements predate the 1976 Act, and as we will discuss later, the Supreme Court has on various occasions declared them to be constitutional requirements of copyright law, mandated by the language of the IP Clause.

The 1976 Act does not provide an explicit definition for the term “works of authorship,” but § 102(a) does set forth a list of eight categories of “works of authorship.” The eight categories of works of authorship identified in § 102(a) are:

- literary works;

- musical works, including any accompanying words;

- dramatic works, including any accompanying music;

- pantomimes and choreographic works;

- pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works;

- motion pictures and other audiovisual works;

- sound recordings; and

- architectural works.

This list is non-exhaustive, in the sense that the Act leaves open the possibility that there are copyrightable “works of authorship” that do not fall within any of these eight categories. However, as a practical matter, the courts and the Copyright Office strive to assign any work deemed copyrightable to one or more of the [*4]eight categories. For example, computer programs are generally classified as “literary works,” even though a computer program in its machine-readable format is simply a string of zeros and ones. In some cases, the rights of a copyright owner can depend on the category into which the work falls. For example, there is a public performance right for “musical works,” but not for “sound recordings.”[1]

Section 102(b) limits the scope of copyrightable subject matter by specifically defining subject matter that cannot be protected by copyright, even if it exists as part of an otherwise copyrightable original work of authorship:

In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.

The substance of 102(b) predates the 1976 Copyright Act, and the exclusion of ideas, procedures, etc., from copyright protection has been identified as a constitutional requirement by the Supreme Court on a number of occasions, as discussed elsewhere in this casebook. Section 102(b) embodies perhaps the most important principle of copyright law, the “idea-expression dichotomy,” which provides that, while the expression of an idea can be copyrighted, the underlying idea itself can never be copyrighted. In the context of the “idea-expression dichotomy,” the term “idea” is given a broad definition that encompasses not only “ideas,” but also methods (i.e., “any … procedure, process, system, [or] method of operation”) and facts (i.e., “any … concept, principle, or discovery”), as set forth in 102(b).

There are other limits on copyrightability. For example, the Act denies copyright protection to works created by the federal government. Additionally, the Copyright Office has identified the following as uncopyrightable subject matter, and will not register them: words and short phrases; familiar symbols or designs; mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering, or coloring; blank forms; standard calendars; and “typeface as typeface.”[2]

B. Originality

Although the IP Clause does not specifically mention “originality,” the U.S. Supreme Court has nonetheless held that the Constitution implicitly requires originality in order for a work to be eligible for copyright protection.[3] As a consequence, Congress is foreclosed from extending copyright protection to non-original works, and the courts strive to interpret copyright law in a manner that only allows copyright protection for original works. In spite of its fundamental importance in setting the threshold requirement for copyrightability, “originality” is not explicitly defined in the Copyright Act. Congress has left that job to the courts. For a definition of “originality” in the copyright sense, we now turn to three seminal decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court that address the issue: Burrow Giles, Bleistein, and Feist, decided in 1884, 1903, and 1991, respectively.

__________

Some things to consider when reading Burrow-Giles:[*5]

- The basis of the plaintiff’s argument that Congress’ decision to extend copyright protection to photographs was unconstitutional.

- The Court’s rationale for rejecting this argument.

- The guidance provided by the Court as to where to draw the line between copyrightable and uncopyrightable photographs.

- The potential applicability of the decision for assessing the copyrightability of works created through the use of artificial intelligence (AI).

- The photographer’s likely forfeiture of copyright in the photograph if he had not included proper notice, including his name and the date of copyright. (The significance of publication with notice is discussed in more detail later in this casebook.)

Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony

111 U.S. 53 (1884)

MILLER, J.

This is a writ of error to the circuit court for the southern district of New York. Plaintiff is a lithographer, and defendant a photographer, with large business in those lines in the city of New York. The suit was commenced by an action at law in which Sarony was plaintiff and the lithographic company was defendant, the plaintiff charging the defendant with violating his copyright in regard to a photograph, the title of which is ‘Oscar Wilde, No. 18.’ A jury being waived, the court made a finding of facts on which a judgment in favor of the plaintiff was rendered for the sum of $600 for the plates and 85,000 copies sold and exposed to sale, and $10 for copies found in his possession, as penalties under section 4965 of the Revised Statutes. Among the finding of facts made by the court the following presents the principal question raised by the assignment of errors in the case:

‘(3) That the plaintiff, about the month of January, 1882, under an agreement with Oscar Wilde, became and was the author, inventor, designer, and proprietor of the photograph in suit, the title of which is ‘Oscar Wilde, No. 18,’ being the number used to designate this particular photograph and of the negative thereof; that the same is a useful, new, harmonious, characteristic, and graceful picture, and that said plaintiff made the same at his place of business in said city of New York, and within the United States, entirely from his own original mental conception, to which he gave visible form by posing the said Oscar Wilde in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories in said photograph, arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression, and from such disposition, arrangement, or representation, made entirely by the plaintiff, he produced the picture in suit, Exhibit A, April 14, 1882, and that the terms ‘author,’ ‘inventor,’ and ‘designer,’ as used in the art of photography and in the complaint, mean the person who so produced the photograph.’

Other findings leave no doubt that plaintiff had taken all the steps required by the act of congress to obtain copyright of this photograph, and section 4952 names photographs, among other things, for which the [*6] author, inventor, or designer may obtain copyright, which is to secure him the sole privilege of reprinting, publishing, copying, and vending the same. That defendant is liable, under that section and section 4965, there can be no question if those sections are valid as they relate to photographs.

Accordingly, the two assignments of error in this court by plaintiff in error are: (1) That the court below decided that congress had and has the constitutional right to protect photographs and negatives thereof by copyright. The second assignment related to the sufficiency of the words ‘Copyright, 1882, by N. Sarony,’ in the photographs, as a notice of the copyright of Napoleon Sarony, under the act of congress on that subject.

With regard to this latter question it is enough to say that the object of the statute is to give notice of the copyright to the public by placing upon each copy, in some visible shape, the name of the author, the existence of the claim of exclusive right, and the date at which this right was obtained. This notice is sufficiently given by the words ‘Copyright, 1882, by N. Sarony,’ found on each copy of the photograph. It clearly shows that a copyright is asserted, the date of which is 1882, and if the name Sarony alone was used, it would be a sufficient designation of the author until it is shown that there is some other Sarony. When, in addition to this, the initial letter of the Christian name Napoleon is also given, the notice is complete.

The constitutional question is not free from difficulty. The eighth section of the first article of the constitution [i.e., the “IP clause”] is the great repository of the powers of congress, and by the eight clause of that section congress is authorized ‘to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing, for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries. [*7]’ The argument here is that a photograph is not a writing nor the production of an author. Under the acts of congress designed to give effect to this section, the persons who are to be benefited are divided into two classes—authors and inventors. The monopoly which is granted to the former is called a copyright: that given to the latter, letters patent, or, in the familiar language of the present day, patent-right. We have then copyright and patent-right, and it is the first of these under which plaintiff asserts a claim for relief. It is insisted, in argument, that a photograph being a reproduction, on paper, of the exact features of some natural object, or of some person, is not a writing of which the producer is the author. Section 4952 of the Revised Statutes places photographs in the same class as things which may be copyrighted with ‘books, maps, charts, dramatic or musical compositions, engravings, cuts, prints, paintings, drawings, statues, statuary, and models or designs intended to be perfected as works of the fine arts.’ ‘According to the practice of legislation in England and America, (says Judge BOUVIER, 2 Law Dict. 363,) the copyright is confined to the exclusive right secured to the author or proprietor of a writing or drawing which may be multiplied by the arts of printing in any of its branches.’

The first congress of the United States, sitting immediately after the formation of the constitution, enacted that the ‘author or authors of any map, chart, book, or books, being a citizen or resident of the United States, shall have the sole right and liberty of printing, reprinting, publishing, and vending the same for the period of fourteen years from the recording of the title thereof in the clerk’s office, as afterwards directed.’ 1 St. p. 124, § 1. This statute not only makes maps and charts subjects of copyright, but mentions them before books in the order of designation. The second section of an act to amend this act, approved April 29, 1802, (2 St. 171,) enacts that from the first day of January thereafter he who shall invent and design, engrave, etch, or work, or from his own works shall cause to be designed and engraved, etched, or worked, any historical or other print or prints, shall have the same exclusive right for the term of 14 years from recording the title thereof as prescribed by law.

By the first section of the act of February 3, 1831, (4 St. 436,) entitled ‘An act to amend the several acts respecting copyright, musical compositions, and cuts, in connection with prints and engravings,’ are added, and the period of protection is extended to 28 years. The caption or title of this act uses the word ‘copyright’ for the first time in the legislation of congress.

The construction placed upon the constitution by the first act of 1790 and the act of 1802, by the men who were contemporary with its formation, many of whom were members of the convention which framed it, is of itself entitled to very great weight, and when it is remembered that the rights thus established have not been disputed during a period of nearly a century, it is almost conclusive. Unless, therefore, photographs can be distinguished in the classification of this point from the maps, charts, designs, engravings, etchings, cuts, and other prints, it is difficult to see why congress cannot make them the subject of copyright as well as the others. These statutes certainly answer the objection that books only, or writing, in the limited sense of a book and its author, are within the constitutional provision. Both these words are susceptible of a more enlarged definition than this. An author in that sense is he to whom anything owes its origin; originator; maker; one who completes a work of science or literature. So, also, no one would now claim that the word ‘writing’ in this clause of the constitution, though the only word used as to subjects in regard to which authors are to be secured, is limited to the actual script of the author, and excludes books and all other printed matter. By writings in that clause is meant the literary productions of those authors, and congress very properly has declared these to include all forms of writing, printing, engravings, etchings, etc., by which [*8] the ideas in the mind of the author are given visible expression. The only reason why photographs were not included in the extended list in the act of 1802 is, probably, that they did not exist, as photography, as an art, was then unknown.

We entertain no doubt that the constitution is broad enough to cover an act authorizing copyright of photographs, so far as they are representatives of original intellectual conceptions of the author.

But it is said that an engraving, a painting, a print, does embody the intellectual conception of its author, in which there is novelty, invention, originality, and therefore comes within the purpose of the constitution in securing its exclusive use or sale to its author, while a photograph is the mere mechanical reproduction of the physical features or outlines of some object, animate or inanimate, and involves no originality of thought or any novelty in the intellectual operation connected with its visible reproduction in shape of a picture. That while the effect of light on the prepared plate may have been a discovery in the production of these pictures, and patents could properly be obtained for the combination of the chemicals, for their application to the paper or other surface, for all the machinery by which the light reflected from the object was thrown on the prepared plate, and for all the improvements in this machinery, and in the materials, the remainder of the process is merely mechanical, with no place for novelty, invention, or originality. It is simply the manual operation, by the use of these instruments and preparations, of transferring to the plate the visible representation of some existing object, the accuracy of this representation being its highest merit. This may be true in regard to the ordinary production of a photograph, and that in such case a copyright is no protection. On the question as thus stated we decide nothing.

The third finding of facts says, in regard to the photograph in question, that it is a ‘useful, new, harmonious, characteristic, and graceful picture, and that plaintiff made the same * * * entirely from his own original mental conception, to which he gave visible form by posing the said Oscar Wilde in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories in said photograph, arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression, and from such disposition, arrangement, or representation, made entirely by plaintiff, he produced the picture in suit.’ These findings, we think, show this photograph to be an original work of art, the product of plaintiff’s intellectual invention, of which plaintiff is the author, and of a class of inventions for which the constitution intended that congress should secure to him the exclusive right to use, publish, and sell, as it has done by section 4952 of the Revised Statutes.

The judgment of the circuit court is accordingly affirmed.

____________

Check Your Understanding – Burrow-Giles.[4]

Question 1. Which of the following is an important holding of Burrow-Giles?

[*9]

Question 2. How does the Burrow-Giles Court interpret the term “writings,” in the context of the IP Clause?

Question 3. True or false. Congress could enact legislation under the IP Clause that extends copyright protection to all photographs.

Socratic Script

What limits does the IP Clause impose on Congress’ ability to expand the scope of copyrightable subject matter?

Why did the Court find it significant that the first congress of the United States, sitting immediately after the formation of the Constitution, enacted copyright legislation providing protection for maps and charts?

[*10]Some things to consider when reading Bleistein:

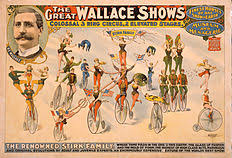

- The question for the Court is essentially whether pictorial illustrations appearing on an advertisement for a circus are sufficiently original for copyright protection.

- In Bleistein, the Court sets a low bar for copyrightability with respect to the perceived “aesthetic value” of a work. What is the policy the Court identifies in support of this low bar, which has come to be referred to as Bleistein’s “aesthetic nondiscrimination” principle?

- What is the question of statutory interpretation that arises in this case, and why did the defendant think it mattered?

Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co.

188 U.S. 239 (1903)

HOLMES, Justice.

This case comes here from the United States circuit court of appeals for the sixth circuit by writ of error. The alleged infringements consisted in the copying in reduced form of three chromolithographs prepared by employees of the plaintiffs for advertisements of a circus owned by one Wallace. Each of the three contained a portrait of Wallace in the corner, and lettering bearing some slight relation to the scheme of decoration, indicating the subject of the design and the fact that the reality was to be seen at the circus. One of the designs was of an ordinary ballet, one of a number of men and women, described as the Stirk family, performing on bicycles, and one of groups of men and women whitened to represent statues. The circuit court directed a verdict for the defendant on the ground that the chromolithographs were not within the protection of the copyright law, and this ruling was sustained by the circuit court of appeals. [*11]

We shall do no more than mention the suggestion that painting and engraving, unless for a mechanical end, are not among the useful arts, the progress of which Congress is empowered by the Constitution to promote. The Constitution does not limit the useful to that which satisfies immediate bodily needs. It is obvious also that the plaintiff’s case is not affected by the fact, if it be one, that the pictures represent actual groups,—visible things. They seem from the testimony to have been composed from hints or description, not from sight of a performance. But even if they had been drawn from the life, that fact would not deprive them of protection. The opposite proposition would mean that a portrait by Velasquez or Whistler was common property because others might try their hand on the same face. Others are free to copy the original. They are not free to copy the copy. The copy is the personal reaction of an individual upon nature. Personality always contains something unique. It expresses its singularity even in handwriting, and a very modest grade of art has in it something irreducible, which is one man’s alone. That something he may copyright unless there is a restriction in the words of the act.

If there is a restriction it is not to be found in the limited pretensions of these particular works. The least pretentious picture has more originality in it than directories and the like, which may be copyrighted. There is no reason to doubt that these prints in their ensemble and in all their details, in their design and particular combinations of figures, lines, and colors, are the original work of the plaintiffs’ designer.

We assume that the construction of Rev. Stat. § 4952, allowing a copyright to the ‘author, designer, or proprietor . . . of any engraving, cut, print . . . [or] chromo’ is affected by the act of 1874. That section provides that, ‘in the construction of this act, the words ‘engraving,’ ‘cut,’ and ‘print’ shall be applied only to pictorial illustrations or works connected with the fine arts.’ We see no reason for taking the words ‘connected with the fine arts’ as qualifying anything except the word ‘works,’ but it would not change our decision if we should assume further that they also qualified ‘pictorial illustrations,’ as the defendant contends.

These chromolithographs are ‘pictorial illustrations.’ The act, however construed, does not mean that ordinary posters are not good enough to be considered within its scope. The antithesis to ‘illustrations or works connected with the fine arts’ is not works of little merit or of humble degree, or illustrations [*12] addressed to the less educated classes; it is ‘prints or labels designed to be used for any other articles of manufacture.’ Certainly works are not the less connected with the fine arts because their pictorial quality attracts the crowd, and therefore gives them a real use,—if use means to increase trade and to help to make money. A picture is none the less a picture, and none the less a subject of copyright, that it is used for an advertisement. And if pictures may be used to advertise soap, or the theatre, or monthly magazines, as they are, they may be used to advertise a circus. Of course, the ballet is as legitimate a subject for illustration as any other. A rule cannot be laid down that would excommunicate the paintings of Degas.

It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one extreme, some works of genius would be sure to miss appreciation. Their very novelty would make them repulsive until the public had learned the new language in which their author spoke. It may be more than doubted, for instance, whether the etchings of Goya or the paintings of Manet would have been sure of protection when seen for the first time. At the other end, copyright would be denied to pictures which appealed to a public less educated than the judge. Yet if they command the interest of any public, they have a commercial value,—it would be bold to say that they have not an aesthetic and educational value,—and the taste of any public is not to be treated with contempt. It is an ultimate fact for the moment, whatever may be our hopes for a change. That these pictures had their worth and their success is sufficiently shown by the desire to reproduce them without regard to the plaintiffs’ rights. We are of opinion that there was evidence that the plaintiffs have rights entitled to the protection of the law.

The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals is reversed; the judgment of the Circuit Court is also reversed and the cause remanded to that court with directions to set aside the verdict and grant a new trial.

HARLAN, Justice, dissenting.

I dissent from the opinion and judgment of this court. The clause of the Constitution giving Congress power to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited terms to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective works and discoveries, does not, as I think, embrace a mere advertisement of a circus.

__________

Check Your Understanding – Bleistein

Question 1. What does the Bleistein Court hold?

Some things to consider when reading Feist:

[*13]

- The Court’s holding regarding the originality required for a work to be copyrightable, and the idea-expression dichotomy.

- The policy basis for the Court’s decision.

- The constitutional basis for the Court’s decision.

- The Court’s discussion of the “sweat of the brow” theory.

- The concept of “thin” copyright protection, which will be explicitly addressed later in this casebook.

- The Court’s statement of the elements of a copyright cause of action.

- The extent to which a factual compilation can be copyrighted, even though the underlying facts cannot be copyrighted.

- Why do you think that Rural inserted fictitious listings into its directory?

Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co.

499 U.S. 340 (1991)

O’CONNOR, Justice.

This case requires us to clarify the extent of copyright protection available to telephone directory white pages.

I

Rural Telephone Service Company, Inc., is a certified public utility that provides telephone service to several communities in northwest Kansas. It is subject to a state regulation that requires all telephone companies operating in Kansas to issue annually an updated telephone directory. Accordingly, as a condition of its monopoly franchise, Rural publishes a typical telephone directory, consisting of white pages and yellow pages. The white pages list in alphabetical order the names of Rural’s subscribers, together with their towns and telephone numbers. The yellow pages list Rural’s business subscribers alphabetically by category and feature classified advertisements of various sizes. Rural distributes its directory free of charge to its subscribers, but earns revenue by selling yellow pages advertisements.

Feist Publications, Inc., is a publishing company that specializes in area-wide telephone directories. Unlike a typical directory, which covers only a particular calling area, Feist’s area-wide directories cover a much larger geographical range, reducing the need to call directory assistance or consult multiple directories. The Feist directory that is the subject of this litigation covers 11 different telephone service areas in 15 counties and contains 46,878 white pages listings—compared to Rural’s approximately 7,700 listings. Like Rural’s directory, Feist’s is distributed free of charge and includes both white pages and yellow pages. Feist and Rural compete vigorously for yellow pages advertising.

As the sole provider of telephone service in its service area, Rural obtains subscriber information quite easily. Persons desiring telephone service must apply to Rural and provide their names and addresses; Rural then assigns them a telephone number. Feist is not a telephone company, let alone one with monopoly status, and therefore lacks independent access to any subscriber information. To obtain white pages listings [*14] for its area-wide directory, Feist approached each of the 11 telephone companies operating in northwest Kansas and offered to pay for the right to use its white pages listings.

Of the 11 telephone companies, only Rural refused to license its listings to Feist. Rural’s refusal created a problem for Feist, as omitting these listings would have left a gaping hole in its area-wide directory, rendering it less attractive to potential yellow pages advertisers. In a decision subsequent to that which we review here, the District Court determined that this was precisely the reason Rural refused to license its listings. The refusal was motivated by an unlawful purpose “to extend its monopoly in telephone service to a monopoly in yellow pages advertising.”

Unable to license Rural’s white pages listings, Feist used them without Rural’s consent. Feist began by removing several thousand listings that fell outside the geographic range of its area-wide directory, then hired personnel to investigate the 4,935 that remained. These employees verified the data reported by Rural and sought to obtain additional information. As a result, a typical Feist listing includes the individual’s street address; most of Rural’s listings do not. Notwithstanding these additions, however, 1,309 of the 46,878 listings in Feist’s 1983 directory were identical to listings in Rural’s 1982–1983 white pages. Four of these were fictitious listings that Rural had inserted into its directory to detect copying.

Rural sued for copyright infringement in the District Court for the District of Kansas taking the position that Feist, in compiling its own directory, could not use the information contained in Rural’s white pages. Rural asserted that Feist’s employees were obliged to travel door-to-door or conduct a telephone survey to discover the same information for themselves. Feist responded that such efforts were economically impractical and, in any event, unnecessary because the information copied was beyond the scope of copyright protection. The District Court granted summary judgment to Rural, explaining that “[c]ourts have consistently held that telephone directories are copyrightable” and citing a string of lower court decisions. The Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit affirmed. We granted certiorari to determine whether the copyright in Rural’s directory protects the names, towns, and telephone numbers copied by Feist.

II

A

This case concerns the interaction of two well-established propositions. The first is that facts are not copyrightable; the other, that compilations of facts generally are. Each of these propositions possesses an impeccable pedigree. That there can be no valid copyright in facts is universally understood. The most fundamental axiom of copyright law is that “[n]o author may copyright his ideas or the facts he narrates.” Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539, 556 (1985). At the same time, however, it is beyond dispute that compilations of facts are within the subject matter of copyright. Compilations were expressly mentioned in the Copyright Act of 1909, and again in the Copyright Act of 1976.

There is an undeniable tension between these two propositions. Many compilations consist of nothing but raw data—i.e., wholly factual information not accompanied by any original written expression. On what basis may one claim a copyright in such a work? Common sense tells us that 100 uncopyrightable facts do not magically change their status when gathered together in one place. Yet copyright law seems to contemplate that compilations that consist exclusively of facts are potentially within its scope. [*15]

The key to resolving the tension lies in understanding why facts are not copyrightable. The sine qua non of copyright is originality. To qualify for copyright protection, a work must be original to the author. See Harper & Row, supra, at 547–549. Original, as the term is used in copyright, means only that the work was independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works), and that it possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity. 1 M. Nimmer & D. Nimmer, Copyright §§ 2.01[A], [B] (1990) (hereinafter Nimmer). To be sure, the requisite level of creativity is extremely low; even a slight amount will suffice. The vast majority of works make the grade quite easily, as they possess some creative spark, “no matter how crude, humble or obvious” it might be. Originality does not signify novelty; a work may be original even though it closely resembles other works so long as the similarity is fortuitous, not the result of copying. To illustrate, assume that two poets, each ignorant of the other, compose identical poems. Neither work is novel, yet both are original and, hence, copyrightable.

Originality is a constitutional requirement. The source of Congress’ power to enact copyright laws is Article I, § 8, cl. 8, of the Constitution, which authorizes Congress to “secur[e] for limited Times to Authors … the exclusive Right to their respective Writings.” In two decisions from the late 19th century—The Trade–Mark Cases, 100 U.S. 82 (1879); and Burrow–Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884)—this Court defined the crucial terms “authors” and “writings.” In so doing, the Court made it unmistakably clear that these terms presuppose a degree of originality.

In The Trade–Mark Cases, the Court addressed the constitutional scope of “writings.” For a particular work to be classified “under the head of writings of authors,” the Court determined, “originality is required.” The Court explained that originality requires independent creation plus a modicum of creativity: “[W]hile the word writings may be liberally construed, as it has been, to include original designs for engraving, prints, &c., it is only such as are original, and are founded in the creative powers of the mind. The writings which are to be protected are the fruits of intellectual labor, embodied in the form of books, prints, engravings, and the like.”

In Burrow–Giles, the Court distilled the same requirement from the Constitution’s use of the word “authors.” The Court defined “author,” in a constitutional sense, to mean “he to whom anything owes its origin; originator; maker.” As in The Trade–Mark Cases, the Court emphasized the creative component of originality. The originality requirement articulated in The Trade–Mark Cases and Burrow–Giles remains the touchstone of copyright protection today. It is the very “premise of copyright law.”

It is this bedrock principle of copyright that mandates the law’s seemingly disparate treatment of facts and factual compilations. “No one may claim originality as to facts.” This is because facts do not owe their origin to an act of authorship. The distinction is one between creation and discovery: The first person to find and report a particular fact has not created the fact; he or she has merely discovered its existence. Census takers, for example, do not “create” the population figures that emerge from their efforts; in a sense, they copy these figures from the world around them. Census data therefore do not trigger copyright because these data are not “original” in the constitutional sense. The same is true of all facts—scientific, historical, biographical, and news of the day. They may not be copyrighted and are part of the public domain available to every person.”

Factual compilations, on the other hand, may possess the requisite originality. The compilation author typically chooses which facts to include, in what order to place them, and how to arrange the collected data [*16] so that they may be used effectively by readers. These choices as to selection and arrangement, so long as they are made independently by the compiler and entail a minimal degree of creativity, are sufficiently original that Congress may protect such compilations through the copyright laws. Thus, even a directory that contains absolutely no protectible written expression, only facts, meets the constitutional minimum for copyright protection if it features an original selection or arrangement.

This protection is subject to an important limitation. The mere fact that a work is copyrighted does not mean that every element of the work may be protected. Originality remains the sine qua non of copyright; accordingly, copyright protection may extend only to those components of a work that are original to the author. Others may copy the underlying facts from the publication, but not the precise words used to present them. In Harper & Row, for example, we explained that President Ford could not prevent others from copying bare historical facts from his autobiography, but that he could prevent others from copying his “subjective descriptions and portraits of public figures.” Where the compilation author adds no written expression but rather lets the facts speak for themselves, the expressive element is more elusive. The only conceivable expression is the manner in which the compiler has selected and arranged the facts. Thus, if the selection and arrangement are original, these elements of the work are eligible for copyright protection. No matter how original the format, however, the facts themselves do not become original through association.

This inevitably means that the copyright in a factual compilation is thin. Notwithstanding a valid copyright, a subsequent compiler remains free to use the facts contained in another’s publication to aid in preparing a competing work, so long as the competing work does not feature the same selection and arrangement.

It may seem unfair that much of the fruit of the compiler’s labor may be used by others without compensation. As Justice Brennan has correctly observed, however, this is not “some unforeseen byproduct of a statutory scheme.” Harper & Row, 471 U.S., at 589. It is, rather, “the essence of copyright,” ibid., and a constitutional requirement. The primary objective of copyright is not to reward the labor of authors, but “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.” Art. I, § 8, cl. 8. To this end, copyright assures authors the right to their original expression, but encourages others to build freely upon the ideas and information conveyed by a work. This principle, known as the idea/expression or fact/expression dichotomy, applies to all works of authorship. As applied to a factual compilation, assuming the absence of original written expression, only the compiler’s selection and arrangement may be protected; the raw facts may be copied at will. This result is neither unfair nor unfortunate. It is the means by which copyright advances the progress of science and art.

This Court has long recognized that the fact/expression dichotomy limits severely the scope of protection in fact-based works. More than a century ago, the Court observed: “The very object of publishing a book on science or the useful arts is to communicate to the world the useful knowledge which it contains. But this object would be frustrated if the knowledge could not be used without incurring the guilt of piracy of the book.” Baker v. Selden, 101 U.S. 99, 103 (1880). We reiterated this point in Harper & Row:

[N]o author may copyright facts or ideas. The copyright is limited to those aspects of the work—termed ‘expression’—that display the stamp of the author’s originality.

“[C]opyright does not prevent subsequent users from copying from a prior author’s work those [*17]constituent elements that are not original—for example … facts, or materials in the public domain—as long as such use does not unfairly appropriate the author’s original contributions.

This, then, resolves the doctrinal tension: Copyright treats facts and factual compilations in a wholly consistent manner. Facts, whether alone or as part of a compilation, are not original and therefore may not be copyrighted. A factual compilation is eligible for copyright if it features an original selection or arrangement of facts, but the copyright is limited to the particular selection or arrangement. In no event may copyright extend to the facts themselves.

B

As we have explained, originality is a constitutionally mandated prerequisite for copyright protection. The Court’s decisions announcing this rule predate the Copyright Act of 1909, but ambiguous language in the 1909 Act caused some lower courts temporarily to lose sight of this requirement.

Most courts construed the 1909 Act correctly, notwithstanding the less-than-perfect statutory language. They understood from this Court’s decisions that there could be no copyright without originality. But some courts misunderstood the statute, focusing their attention on § 5 of the Act, [which identified compilations as a category of potentially copyrightable work]. Section 5 did not purport to say that all compilations were automatically copyrightable. Nevertheless, the fact that factual compilations were mentioned specifically in § 5 led some courts to infer erroneously that directories and the like were copyrightable per se, without any further or precise showing of original—personal—authorship.

Making matters worse, these courts developed a new theory to justify the protection of factual compilations. Known alternatively as “sweat of the brow” or “industrious collection,” the underlying notion was that copyright was a reward for the hard work that went into compiling facts. The classic formulation of the doctrine appeared in Jeweler’s Circular Publishing Co., 281 F., at 88:

The right to copyright a book upon which one has expended labor in its preparation does not depend upon whether the materials which he has collected consist or not of matters which are publici juris, or whether such materials show literary skill or originality, either in thought or in language, or anything more than industrious collection. The man who goes through the streets of a town and puts down the names of each of the inhabitants, with their occupations and their street number, acquires material of which he is the author.

The “sweat of the brow” doctrine had numerous flaws, the most glaring being that it extended copyright protection in a compilation beyond selection and arrangement—the compiler’s original contributions—to the facts themselves. Under the doctrine, the only defense to infringement was independent creation. A subsequent compiler was not entitled to take one word of information previously published, but rather had to independently work out the matter for himself, so as to arrive at the same result from the same common sources of information. “Sweat of the brow” courts thereby eschewed the most fundamental axiom of copyright law—that no one may copyright facts or ideas.

Without a doubt, the “sweat of the brow” doctrine flouted basic copyright principles. Throughout history, copyright law has recognized a greater need to disseminate factual works than works of fiction or fantasy. But “sweat of the brow” courts took a contrary view; they handed out proprietary interests in facts and [*18] declared that authors are absolutely precluded from saving time and effort by relying upon the facts contained in prior works. Protection for the fruits of such research may in certain circumstances be available under a theory of unfair competition. But to accord copyright protection on this basis alone distorts basic copyright principles in that it creates a monopoly in public domain materials without the necessary justification of protecting and encouraging the creation of “writings” by “authors.”

C

“Sweat of the brow” decisions did not escape the attention of the Copyright Office. When Congress decided to overhaul the copyright statute and asked the Copyright Office to study existing problems, see Mills Music, Inc. v. Snyder, 469 U.S. 153, 159, 105 S.Ct. 638, 642, 83 L.Ed.2d 556 (1985), the Copyright Office promptly recommended that Congress clear up the confusion in the lower courts as to the basic standards of copyrightability. The Register of Copyrights explained in his first report to Congress that “originality” was a “basic requisit[e]” of copyright under the 1909 Act, but that “the absence of any reference to [originality] in the statute seems to have led to misconceptions as to what is copyrightable matter.” Report of the Register of Copyrights on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law, 87th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 9 (H. Judiciary Comm. Print 1961). The Register suggested making the originality requirement explicit. Ibid.

[When Congress enacted the Copyright Act of 1976, it made the originality requirement explicit by dropping the reference to “all the writings of an author” and replaced it with the phrase “original works of authorship.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a).] In making explicit the originality requirement, Congress announced that it was merely clarifying existing law: “The two fundamental criteria of copyright protection [are] originality and fixation in tangible form…. The phrase ‘original works of authorship,’ which is purposely left undefined, is intended to incorporate without change the standard of originality established by the courts under the present [1909] copyright statute.” H.R.Rep. No. 94–1476, p. 51 (1976) (emphasis added) (hereinafter H.R.Rep.); S.Rep. No. 94–473, p. 50 (1975), U.S.Code Cong. & Admin.News 1976, pp. 5659, 5664 (emphasis added) (hereinafter S.Rep.).

To ensure that the mistakes of the “sweat of the brow” courts would not be repeated, Congress took additional measures. For example, § 3 of the 1909 Act had stated that copyright protected only the “copyrightable component parts” of a work, but had not identified originality as the basis for distinguishing those component parts that were copyrightable from those that were not. The 1976 Act deleted this section and replaced it with § 102(b), which identifies specifically those elements of a work for which copyright is not available: “In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.” Section 102(b) is universally understood to prohibit any copyright in facts. As with § 102(a), Congress emphasized that § 102(b) did not change the law, but merely clarified it: “Section 102(b) in no way enlarges or contracts the scope of copyright protection under the present law. Its purpose is to restate … that the basic dichotomy between expression and idea remains unchanged.” H.R.Rep., at 57; S.Rep., at 54, U.S.Code Cong. & Admin.News 1976, p. 5670.

Congress took another step to minimize confusion by deleting the specific mention of “directories … and other compilations” in § 5 of the 1909 Act. As mentioned, this section had led some courts to conclude that directories were copyrightable per se and that every element of a directory was protected. In its place, [*19] Congress enacted two new provisions. First, to make clear that compilations were not copyrightable per se, Congress provided a definition of the term “compilation.” Second, to make clear that the copyright in a compilation did not extend to the facts themselves, Congress enacted § 103.

The definition of “compilation” is found in § 101 of the 1976 Act. It defines a “compilation” in the copyright sense as “a work formed by the collection and assembling of preexisting materials or of data that are selected, coordinated, or arranged in such a way that the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship” (emphasis added).

The purpose of the statutory definition is to emphasize that collections of facts are not copyrightable per se. It conveys this message through its tripartite structure, as emphasized above by the italics. The statute identifies three distinct elements and requires each to be met for a work to qualify as a copyrightable compilation: (1) the collection and assembly of pre-existing material, facts, or data; (2) the selection, coordination, or arrangement of those materials; and (3) the creation, by virtue of the particular selection, coordination, or arrangement, of an “original” work of authorship.

At first glance, the first requirement does not seem to tell us much. It merely describes what one normally thinks of as a compilation—a collection of pre-existing material, facts, or data. What makes it significant is that it is not the sole requirement. It is not enough for copyright purposes that an author collects and assembles facts. To satisfy the statutory definition, the work must get over two additional hurdles. In this way, the plain language indicates that not every collection of facts receives copyright protection. Otherwise, there would be a period after “data.”

The third requirement is also illuminating. It emphasizes that a compilation, like any other work, is copyrightable only if it satisfies the originality requirement (“an original work of authorship”). Although § 102 states plainly that the originality requirement applies to all works, the point was emphasized with regard to compilations to ensure that courts would not repeat the mistake of the “sweat of the brow” courts by concluding that fact-based works are treated differently and measured by some other standard.

The key to the statutory definition is the second requirement. It instructs courts that, in determining whether a fact-based work is an original work of authorship, they should focus on the manner in which the collected facts have been selected, coordinated, and arranged. This is a straightforward application of the originality requirement. Facts are never original, so the compilation author can claim originality, if at all, only in the way the facts are presented. To that end, the statute dictates that the principal focus should be on whether the selection, coordination, and arrangement are sufficiently original to merit protection.

Not every selection, coordination, or arrangement will pass muster. This is plain from the statute. It states that, to merit protection, the facts must be selected, coordinated, or arranged “in such a way” as to render the work as a whole original. This implies that some “ways” will trigger copyright, but that others will not. Otherwise, the phrase “in such a way” is meaningless and Congress should have defined “compilation” simply as “a work formed by the collection and assembly of preexisting materials or data that are selected, coordinated, or arranged.” That Congress did not do so is dispositive. In accordance with the established principle that a court should give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute, we conclude that the statute envisions that there will be some fact-based works in which the selection, coordination, and arrangement are not sufficiently original to trigger copyright protection. [*20]

As discussed earlier, however, the originality requirement is not particularly stringent. A compiler may settle upon a selection or arrangement that others have used; novelty is not required. Originality requires only that the author make the selection or arrangement independently (i.e., without copying that selection or arrangement from another work), and that it display some minimal level of creativity. Presumably, the vast majority of compilations will pass this test, but not all will. There remains a narrow category of works in which the creative spark is utterly lacking or so trivial as to be virtually nonexistent. Such works are incapable of sustaining a valid copyright.

Even if a work qualifies as a copyrightable compilation, it receives only limited protection. This is the point of § 103 of the Act. Section 103 explains that “[t]he subject matter of copyright … includes compilations,” § 103(a), but that copyright protects only the author’s original contributions—not the facts or information conveyed:

The copyright in a compilation … extends only to the material contributed by the author of such work, as distinguished from the preexisting material employed in the work, and does not imply any exclusive right in the preexisting material. § 103(b).

As § 103 makes clear, copyright is not a tool by which a compilation author may keep others from using the facts or data he or she has collected. The 1909 Act did not require, as “sweat of the brow” courts mistakenly assumed, that each subsequent compiler must start from scratch and is precluded from relying on research undertaken by another. Rather, the facts contained in existing works may be freely copied because copyright protects only the elements that owe their origin to the compiler—the selection, coordination, and arrangement of facts.

In summary, the 1976 revisions to the Copyright Act leave no doubt that originality, not “sweat of the brow,” is the touchstone of copyright protection in directories and other fact-based works. Nor is there any doubt that the same was true under the 1909 Act.

III

There is no doubt that Feist took from the white pages of Rural’s directory a substantial amount of factual information. At a minimum, Feist copied the names, towns, and telephone numbers of 1,309 of Rural’s subscribers. Not all copying, however, is copyright infringement. To establish infringement, two elements must be proven: (1) ownership of a valid copyright, and (2) copying of constituent elements of the work that are original. The first element is not at issue here; Feist appears to concede that Rural’s directory, considered as a whole, is subject to a valid copyright because it contains some foreword text, as well as original material in its yellow pages advertisements.

The question is whether Rural has proved the second element. In other words, did Feist, by taking 1,309 names, towns, and telephone numbers from Rural’s white pages, copy anything that was “original” to Rural? Certainly, the raw data does not satisfy the originality requirement. Rural may have been the first to discover and report the names, towns, and telephone numbers of its subscribers, but this data does not “owe its origin” to Rural. Rather, these bits of information are uncopyrightable facts; they existed before Rural reported them and would have continued to exist if Rural had never published a telephone directory.

The question that remains is whether Rural selected, coordinated, or arranged these uncopyrightable facts [*21] in an original way. As mentioned, originality is not a stringent standard; it does not require that facts be presented in an innovative or surprising way. It is equally true, however, that the selection and arrangement of facts cannot be so mechanical or routine as to require no creativity whatsoever. The standard of originality is low, but it does exist.

The selection, coordination, and arrangement of Rural’s white pages do not satisfy the minimum constitutional standards for copyright protection. As mentioned at the outset, Rural’s white pages are entirely typical. Persons desiring telephone service in Rural’s service area fill out an application and Rural issues them a telephone number. In preparing its white pages, Rural simply takes the data provided by its subscribers and lists it alphabetically by surname. The end product is a garden-variety white pages directory, devoid of even the slightest trace of creativity.

Rural’s selection of listings could not be more obvious: It publishes the most basic information—name, town, and telephone number—about each person who applies to it for telephone service. This is “selection” of a sort, but it lacks the modicum of creativity necessary to transform mere selection into copyrightable expression. Rural expended sufficient effort to make the white pages directory useful, but insufficient creativity to make it original.

Nor can Rural claim originality in its coordination and arrangement of facts. The white pages do nothing more than list Rural’s subscribers in alphabetical order. This arrangement may, technically speaking, owe its origin to Rural; no one disputes that Rural undertook the task of alphabetizing the names itself. But there is nothing remotely creative about arranging names alphabetically in a white pages directory. It is an age-old practice, firmly rooted in tradition and so commonplace that it has come to be expected as a matter of course. It is not only unoriginal, it is practically inevitable. This time-honored tradition does not possess the minimal creative spark required by the Copyright Act and the Constitution.

We conclude that the names, towns, and telephone numbers copied by Feist were not original to Rural and therefore were not protected by the copyright in Rural’s combined white and yellow pages directory. As a constitutional matter, copyright protects only those constituent elements of a work that possess more than a de minimis quantum of creativity. Rural’s white pages, limited to basic subscriber information and arranged alphabetically, fall short of the mark. As a statutory matter, 17 U.S.C. § 101 does not afford protection from copying to a collection of facts that are selected, coordinated, and arranged in a way that utterly lacks originality. Given that some works must fail, we cannot imagine a more likely candidate. Indeed, were we to hold that Rural’s white pages pass muster, it is hard to believe that any collection of facts could fail.

Because Rural’s white pages lack the requisite originality, Feist’s use of the listings cannot constitute infringement. This decision should not be construed as demeaning Rural’s efforts in compiling its directory, but rather as making clear that copyright rewards originality, not effort. As this Court noted more than a century ago, “great praise may be due to the plaintiffs for their industry and enterprise in publishing this paper, yet the law does not contemplate their being rewarded in this way.” Baker v. Selden, 101 U.S., at 105.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is Reversed.

__________

[*22]

Check Your Understanding – Feist

Question 1. According to Feist, what is the most fundamental axiom of copyright law?

Question 2. What does the Constitution require in order for a work to qualify for copyright protection?

Question 3. What are the two fundamental criteria of copyright protection? [*23]?

Question 4. According to Feist, what elements must be proven in order to establish copyright infringement?

Question 5. True or false: The Feist Court concluded that Rural’s selection, coordination, and arrangement of phone listings was not copyrightable because it lacked the modicum of creativity necessary to transform mere selection into copyrightable expression.

Socratic Script

What is required in order for a compilation of facts to be afforded copyright protection?

Give an example of a work that is copyrighted, but not every element of the work is protected.

Some things to consider when reading Meshwerks:

- Copyright registration will be addressed later in the book, but for now, note that a copyright claimant must register (or at least attempt to register) its copyright with the Copyright Office prior to bringing a lawsuit for infringement of that copyright. Pay attention to the role registration plays in this case. [*24]

- The “delicate balance” that the IP Clause and Copyright Act seek to strike.

- The court’s application of Feist and Burrow–Giles to computer-generated illustrations, more particularly, digital models of automobiles.

- The implicit reference to “sweat of the brow,” and Feist’s rejection of that doctrine.

- Why the court finds that the digital models are insufficiently original for copyright protection.

- Potential implications of this decision for the copyrightability of photographs and other images that realistically portray something (or someone) that exists in the real world.

Meshwerks, Inc. v. Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc.

528 F.3d 1258 (10th Cir. 2008)

GORSUCH, Circuit Judge.

This case calls on us to apply copyright principles to a relatively new technology: digital modeling. Meshwerks insists that, contrary to the district court’s summary judgment determination, its digital models of Toyota cars and trucks are sufficiently original to warrant copyright protection. Meshwerks’ models, which form the base layers of computerized substitutes for product photographs in advertising, are unadorned, digital wire-frames of Toyota’s vehicles. While fully appreciating that digital media present new frontiers for copyrightable creative expression, in this particular case the uncontested facts reveal that Meshwerks’ models owe their designs and origins to Toyota and deliberately do not include anything original of their own; accordingly, we hold that Meshwerks’ models are not protected by copyright and affirm.

I

A

In 2003, and in conjunction with Saatchi & Saatchi, its advertising agency, Toyota began work on its model-year 2004 advertising campaign. Saatchi and Toyota agreed that the campaign would involve, among other things, digital models of Toyota’s vehicles for use on Toyota’s website and in various other media. These digital models have substantial advantages over the product photographs for which they substitute. With a few clicks of a computer mouse, the advertiser can change the color of the car, its surroundings, and even edit its physical dimensions to portray changes in vehicle styling; before this innovation, advertisers had to conduct new photo shoots of whole fleets of vehicles each time the manufacturer made even a small design change to a car or truck.

To supply these digital models, Saatchi and Toyota hired Grace & Wild, Inc. (“G & W”). In turn, G & W subcontracted with Meshwerks to assist with two initial aspects of the project—digitization and modeling. Digitizing involves collecting physical data points from the object to be portrayed. In the case of Toyota’s vehicles, Meshwerks took copious measurements of Toyota’s vehicles by covering each car, truck, and van with a grid of tape and running an articulated arm tethered to a computer over the vehicle to measure all points of intersection in the grid. Based on these measurements, modeling software then generated a digital image resembling a wire-frame model. In other words, the vehicles’ data points (measurements) were [*25]mapped onto a computerized grid and the modeling software connected the dots to create a “wire frame” of each vehicle.

At this point, however, the on-screen image remained far from perfect and manual “modeling” was necessary. Meshwerks personnel fine-tuned or, as the company prefers it, “sculpted,” the lines on screen to resemble each vehicle as closely as possible. Approximately 90 percent of the data points contained in each final model, Meshwerks represents, were the result not of the first-step measurement process, but of the skill and effort its digital sculptors manually expended at the second step. For example, some areas of detail, such as wheels, headlights, door handles, and the Toyota emblem, could not be accurately measured using current technology; those features had to be added at the second “sculpting” stage, and Meshwerks had to recreate those features as realistically as possible by hand, based on photographs. Even for areas that were measured, Meshwerks faced the challenge of converting measurements taken of a three-dimensional car into a two-dimensional computer representation; to achieve this, its modelers had to sculpt, or move, data points to achieve a visually convincing result. The purpose and product of these processes, after nearly 80 to 100 hours of effort per vehicle, were two-dimensional wire-frame depictions of Toyota’s vehicles that appeared three-dimensional on screen, but were utterly unadorned—lacking color, shading, and other details. Attached to this opinion as Appendix A are sample screen-prints of one of Meshwerks’ digital wire-frame models.

With Meshwerks’ wire-frame products in hand, G & W then manipulated the computerized models by, first, adding detail, the result of which appeared on screen as a “tightening” of the wire frames, as though significantly more wires had been added to the frames, or as though they were made of a finer mesh. Next, G & W digitally applied color, texture, lighting, and animation for use in Toyota’s advertisements. An example of G & W’s work product is attached as Appendix B to this opinion. G & W’s digital models were then sent to Saatchi to be employed in a number of advertisements prepared by Saatchi and Toyota in various print, online, and television media.

B

This dispute arose because, according to Meshwerks, it contracted with G & W for only a single use of its models—as part of one Toyota television commercial—and neither Toyota nor any other defendant was allowed to use the digital models created from Meshwerks’ wire-frames in other advertisements. Thus, Meshwerks contends defendants improperly—in violation of copyright laws as well as the parties’ agreement—reused and redistributed the models created by Meshwerks in a host of other media. In support of the allegations that defendants misappropriated its intellectual property, Meshwerks points to the fact that it sought and received copyright registration on its wire-frame models.[5]

In due course, defendants moved for summary judgment on the theory that Meshwerks’ wire-frame models lacked sufficient originality to be protected by copyright. Specifically, defendants argued that any original expression found in Meshwerks’ products was attributable to the Toyota designers who conceived of the vehicle designs in the first place; accordingly, defendants’ use of the models could not give rise to a claim for copyright infringement.

The district court agreed. It found that the wire-frame models were merely copies of Toyota’s products, not sufficiently original to warrant copyright protection, and stressed that Meshwerks’ “intent was to replicate, [*26]as exactly as possible, the image of certain Toyota vehicles.” Because there was no valid copyright, there could be no infringement, and, having granted summary judgment on the federal copyright claim, the district court declined to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over Meshwerks’ state-law contract claim. Today, Meshwerks asks us to reverse and hold its digital, wire-frame models sufficiently original to warrant copyright protection.

II

To make a case for copyright infringement, Meshwerks must show (1) it owns a valid copyright, and (2) defendants copied constituent elements of the work that are original to Meshwerks. Our inquiry in this case focuses on the first of these tests—that is, on the question whether Meshwerks held a valid copyright in its digital wire-frame models. Because Meshwerks obtained registration certificates for its models from the Copyright Office, we presume that it holds a valid copyright. See 17 U.S.C. § 410(c); Palladium Music, Inc. v. EatSleepMusic, Inc., 398 F.3d 1193, 1196 (10th Cir. 2005). At the same time, defendants may overcome this presumption by presenting evidence and legal argument sufficient to establish that the works in question were not entitled to copyright protection. Because this case comes to us on summary judgment, we review the question whether Meshwerks holds a valid copyright de novo and will affirm the district court’s judgment only if, viewing all of the facts in the light most favorable to Meshwerks, we are able to conclude that “there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that [defendants are] entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” Fed.R.Civ.P. 56(c).

A

The Constitution authorizes Congress “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8. The Supreme Court has emphasized that the power afforded by this provision—namely, to give an author exclusive authority over a work—rests in part on a “presuppos[ition]” that the work contains “a degree of originality.” Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 346 (1991). Congress has recognized this same point, extending copyright protection only to “original works of authorship….” 17 U.S.C. § 102 (emphasis added). Originality, thus, is said to be “[t]he sine qua non of copyright.” Feist, 499 U.S. at 345. That is, not every work of authorship, let alone every aspect of every work of authorship, is protectable in copyright; only original expressions are protected. This constitutional and statutory principle seeks to strike a delicate balance—rewarding (and thus encouraging) those who contribute something new to society, while also allowing (and thus stimulating) others to build upon, add to, and develop those creations.

What exactly does it mean for a work to qualify as “original”? In Feist, the Supreme Court clarified that the work must be “independently created by the author (as opposed to copied from other works).” In addition, the work must “possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity.”

The parties focus most of their energy in this case on the question whether Meshwerks’ models qualify as independent creations, as opposed to copies of Toyota’s handiwork. But what can be said, at least based on received copyright doctrine, to distinguish an independent creation from a copy? And how might that doctrine apply in an age of virtual worlds and digital media that seek to mimic the “real” world, but often do so in ways that undoubtedly qualify as (highly) original? While there is little authority explaining how [*27]our received principles of copyright law apply to the relatively new digital medium before us, some lessons may be discerned from how the law coped in an earlier time with a previous revolution in technology: photography.

Photography was initially met by critics with a degree of skepticism: a photograph, some said, “copies everything and explains nothing,” and it was debated whether a camera could do anything more than merely record the physical world. These largely aesthetic debates migrated into legal territory when Oscar Wilde toured the United States in the 1880s and sought out Napoleon Sarony for a series of publicity photographs to promote the event. Burrow– Giles, a lithography firm, quickly copied one of Sarony’s photos and sold 85,000 prints without the photographer’s permission. Burrow–Giles defended its conduct on the ground that the photograph was a “mere mechanical reproduction of the physical features” of Wilde and thus not copyrightable. Burrow–Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 59 (1884). Recognizing that Oscar Wilde’s inimitable visage does not belong, or “owe its origins” to any photographer, the Supreme Court noted that photographs may well sometimes lack originality and are thus not per se copyrightable. At the same time, the Court held, a copyright may be had to the extent a photograph involves “posing the said Oscar Wilde in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories in said photograph, arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines, arranging and disposing the light and shade, suggesting and evoking the desired expression….” Accordingly, the Court indicated, photographs are copyrightable, if only to the extent of their original depiction of the subject. Wilde’s image is not copyrightable; but to the extent a photograph reflects the photographer’s decisions regarding pose, positioning, background, lighting, shading, and the like, those elements can be said to “owe their origins” to the photographer, making the photograph copyrightable, at least to that extent.

As the Court more recently explained in Feist, the operative distinction is between, on the one hand, ideas or facts in the world, items that cannot be copyrighted, and a particular expression of that idea or fact, that can be. This principle, known as the idea/expression or fact/expression dichotomy, applies to all works of authorship. In the case of photographs, for which Meshwerks’ digital models were designed to serve as practically advantageous substitutes, authors are entitled to copyright protection only for the incremental contribution represented by their interpretation or expression of the objects of their attention.

B

Applying these principles, evolved in the realm of photography, to the new medium that has come to supplement and even in some ways to supplant it, we think Meshwerks’ models are not so much independent creations as (very good) copies of Toyota’s vehicles. In reaching this conclusion we rely on (1) an objective assessment of the particular models before us and (2) the parties’ purpose in creating them. All the same, we do not doubt for an instant that the digital medium before us, like photography before it, can be employed to create vivid new expressions fully protectable in copyright.

1

Key to our evaluation of this case is the fact that Meshwerks’ digital wire-frame computer models depict Toyota’s vehicles without any individualizing features: they are untouched by a digital paintbrush; they are not depicted in front of a palm tree, whizzing down the open road, or climbing up a mountainside. Put another way, Meshwerks’ models depict nothing more than unadorned Toyota vehicles—the [*28]car as car. See Appendix A. And the unequivocal lesson from Feist is that works are not copyrightable to the extent they do not involve any expression apart from the raw facts in the world. A photographer is entitled to copyright solely based on lighting, angle, perspective, and the other ingredients that traditionally apply to that art-form.” It seems to us that exactly the same holds true with the digital medium now before us: the facts in this case unambiguously show that Meshwerks did not make any decisions regarding lighting, shading, the background in front of which a vehicle would be posed, the angle at which to pose it, or the like—in short, its models reflect none of the decisions that can make depictions of things or facts in the world, whether Oscar Wilde or a Toyota Camry, new expressions subject to copyright protection.

The primary case on which Meshwerks asks us to rely actually reinforces this conclusion. In Ets–Hokin v. Skyy Spirits, Inc., 225 F.3d 1068 (9th Cir. 2000) (Skyy I ), the Ninth Circuit was faced with a suit brought by a plaintiff photographer who alleged that the defendant had infringed on his commercial photographs of a Skyy-brand vodka bottle. The court held that the vodka bottle, as a “utilitarian object,” a fact in the world, was not itself (at least usually) copyrightable. At the same time, the court recognized that plaintiff’s photos reflected decisions regarding “lighting, shading, angle, background, and so forth,” and to the extent plaintiff’s photographs reflected such original contributions the court held they could be copyrighted. In so holding, the Ninth Circuit reversed a district court’s dismissal of the case and remanded the matter for further proceedings, and Meshwerks argues this analysis controls the outcome of its case.

But Skyy I tells only half the story. The case soon returned to the court of appeals, and the court held that the defendant’s photos, which differed in terms of angle, lighting, shadow, reflection, and background, did not infringe on the plaintiff’s copyrights. Ets–Hokin v. Skyy Spirits, Inc., 323 F.3d 763, 765 (9th Cir. 2003) (Skyy II ). Why? The only constant between the plaintiff’s photographs and the defendant’s photographs was the bottle itself, id. at 766, and an accurate portrayal of the unadorned bottle could not be copyrighted. Facts and ideas are the public’s domain and open to exploitation to ensure the progress of science and the useful arts. Only original expressions of those facts or ideas are copyrightable, leaving the plaintiff in the Skyy case with an admittedly “thin” copyright offering protection perhaps only from exact duplication by others.

The teaching of Skyy I and II, then, is that the vodka bottle, because it did not owe its origins to the photographers, had to be filtered out to determine what copyrightable expression remained. And, by analogy—though not perhaps the one Meshwerks had in mind—we hold that the unadorned images of Toyota’s vehicles cannot be copyrighted by Meshwerks and likewise must be filtered out. To the extent that Meshwerks’ digital wire-frame models depict only those unadorned vehicles, having stripped away all lighting, angle, perspective, and “other ingredients” associated with an original expression, we conclude that they have left no copyrightable matter.

Confirming this conclusion as well is the peculiar place where Meshwerks stood in the model-creation pecking order. On the one hand, Meshwerks had nothing to do with designing the appearance of Toyota’s vehicles, distinguishing them from any other cars, trucks, or vans in the world. That expressive creation took place before Meshwerks happened along, and was the result of work done by Toyota and its designers; indeed, at least six of the eight vehicles at issue are still covered by design patents belonging to Toyota and protecting the appearances of the objects for which they are issued. On the other hand, how the models Meshwerks created were to be deployed in advertising—including the backgrounds, lighting, angles, and [*29]colors—were all matters left to those (G & W, Saatchi, and 3D Recon) who came after Meshwerks left the scene. Meshwerks thus played a narrow, if pivotal, role in the process by simply, if effectively, copying Toyota’s vehicles into a digital medium so they could be expressively manipulated by others.